COMING TO THE WEST

by Natasha Kurchanova. Photo by Open Minder.*

I had a safe childhood growing up in Brezhnev-era Soviet Russia. My family was a rather typical one, according to the principle formulated by Leo Tolstoy in Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

I lived with a father, mother, younger brother, grandmother, and grandfather in a two-bedroom Khrushchyovka building on Vasilyevsky Island, Leningrad. To Americans, it may sound incredibly crowded and like poor living conditions, but I did not experience it as such. I felt loved and cared for; my kindergarten and school were around the corner from my apartment building. On weekends and during summers, we would either take a train or drive to the country house about 100 kilometers outside of Leningrad. We’d also have throngs of relatives visiting us, mostly on weekends. My grandparents had large families, and we had little respite from innumerable aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces, and nephews, some of whom lived nearby in the city and some in other cities in Russia, Ukraine, and Byelorussia. A lot of the time, they would visit us; sometimes, we would visit them.

I remember the atmosphere of joy and the pleasure of seeing each other and being in each other’s company; there was rarely bickering or quarrels. Reflecting on it, my extended family’s joyfulness and a sense of cohesiveness appears almost unreal. Sometimes I wonder that the massive trauma of World War II, much of which was fought on Soviet Union territory, contributed to the family’s sense of unity.

Everyone among my grandparents’ and parents’ generations was a World War II veteran or survivor; among my immediate family, my grandfather and his brothers fought in the war and were wounded multiple times; my grandmother and my mother survived the Blockade of Leningrad; my father was interred in camp as a young prisoner of war. Growing up, I heard many stories about the war, stories of struggle and survival. I wonder if the sheer joy of staying alive after several years of brutal slaughter made the older generations of my family want to appreciate life and enjoy it to the fullest. Whatever the cause, I remember growing up in a tightly knit, happy family.

As I was coming of age, it became clear that, regardless of how much my family benefited from our country’s victory in the war politically, the Soviet Union had a problem. Only my grandfather was listening to the official decree announcements of the Communist Party with attention and awe; no one among my peers or even my parents’ generation was taking them seriously.

People went to obligatory demonstrations on May 1 and October 17 only due to fear of retribution from their party bosses; they appeared to resent not only this obligation, but also any other task imposed on them by the party. Morale was low; any dissent was forcefully suppressed. Art and culture were regulated from above by party orders and decrees, and anyone who fell out of line was in danger of being sent the Gulag or a psychiatric asylum.

In the sphere of economics, the Soviet infrastructure was crumbling; there was no incentive for manufacturers to make things that would appeal to the public because there was no competition or free market — customers had no choice but to buy second-rate, shabby products manufactured in the USSR or in Eastern Bloc countries. Often, it was impossible to find toilet paper, forget about fashionable outfits or decent furniture. Even though travel to and communication with the West was restricted, glimpses of its material abundance were seeping through the cracks of Soviet censorship in the form of magazines brought by foreign students and classic French, Italian, and Hollywood films.

Falling in love with one of those foreign students and coming to the United States in the mid-1980s was not an accident. My American husband represented the “good” West, and I trusted him to teach me about life in his country, which was becoming my country as well. I left Russia when Chernenko was the General Secretary of the Party, a few months before Gorbachev’s era. The fall of the Soviet Union happened without me in the country, albeit I tried to talk with my family weekly. It was a difficult experience, as people I loved suffered through food shortages and a complete disintegration of the safety net around them. Even though Gorbachev tried to regulate the transition to free economy and preserve vestiges of Soviet power, the forces he set in motion were out of his control.

Yeltsin spearheaded the revolt against Gorbachev’s government, and his defiant stance received wide support. Watching the rapid unfolding of revolutionary events from the outside was both exhilarating and confusing. Gorbachev appeared to be reasonable and trustworthy; Yeltsin seemed to have been adept at theatrical gestures and attracting popular support. Nonetheless, both sides were for reforms and looked to the West for assurance and support, giving Americans in particular an enormous power to influence Russian politics.

Something went wrong with the American support of the idea that democracy in Russia could be built solely through the emphasis on economic restructuring, by giving individuals hungry for money and power what they wanted, while turning a blind eye to due democratic process. As the events of the 1990s unfolded with the oligarchs and Putin forming a governing alliance, I caught myself thinking of the ironic incongruity of an apocalyptic beginning and the less-than-glorious end of the twentieth century in Russian history. It started off with a dream about building a better world for the lowest and poorest classes of the society, and it ended with a wealthy oligarchy taking the reins of power and turning an enormously creative and restless country into a bastion of nationalism and orthodoxy.

History shows that what happens in Russia politically is likely to affect the rest of the world. Unfortunately, the United States is living this experience in the moment, with its president admiring the Russian ruler and following in his footsteps to squelch democracy. ■

-

Natasha Kurchanova, PhD, is a candidate at IPTAR.Her doctorate is in art history. Apart from studying psychoanalysis and working as a clinician, she contributes reviews and interviews with artists for such publications as Studio International, The Candidate Journal, The Burlington Magazine, CAA Reviews, Bomb Magazine, Art Journal, and other publications. She is on the editorial board of The Candidate Journal.

-

Email: natasha@pipeline.com

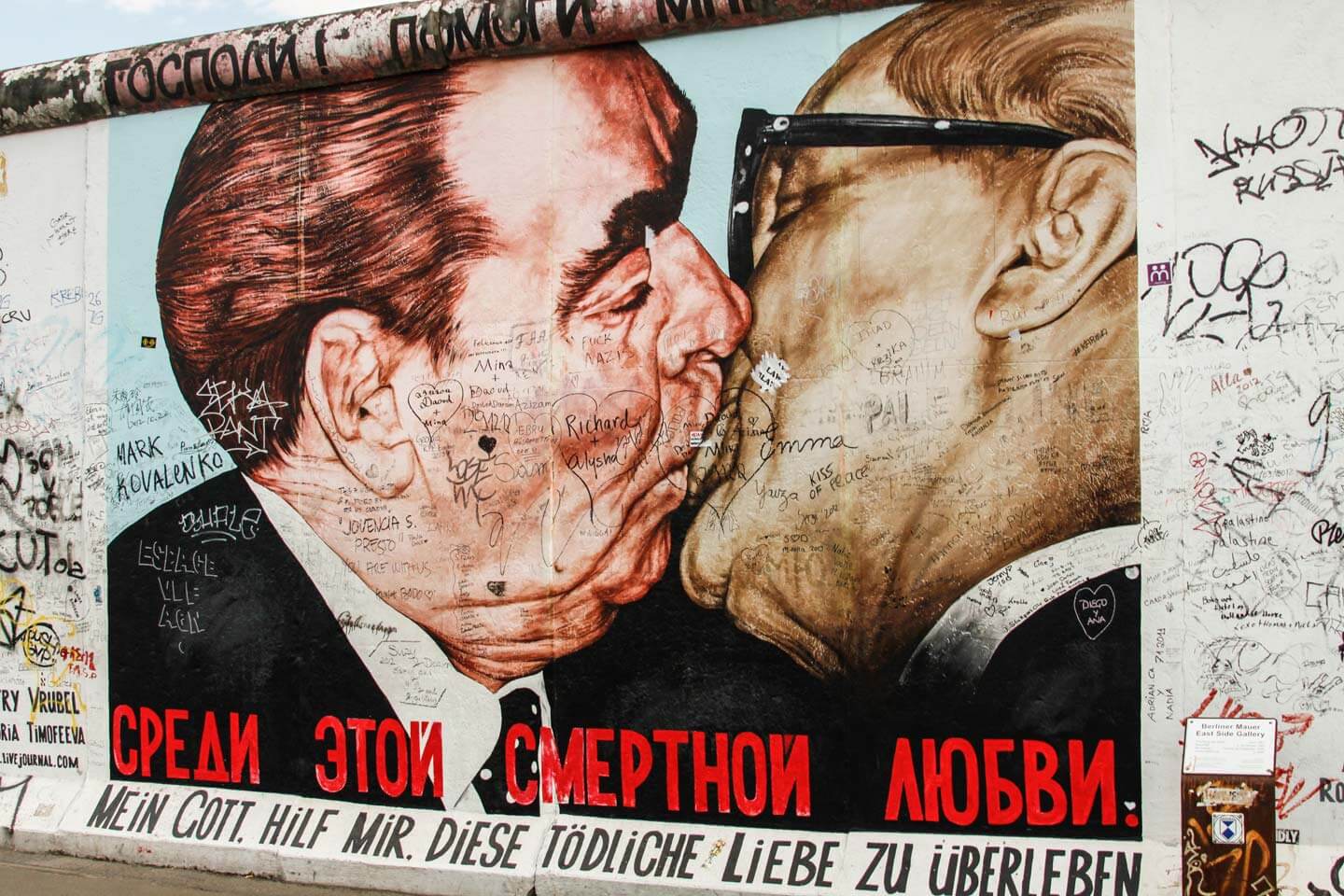

- Photo by Open Minder. A segment of the Berlin Wall with the graffiti painting “My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love” showing Brezhnev kissing Erich Honecker.

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |