A VIEW OF THE ELECTION FROM THE OUTPOSTS OF OLD AGE

by Janet Fisher

An eighty-four year old woman who has been in therapy for years for chronic anxiety has a satisfying and still thriving career, a solid marriage, and a large, sprawling and emotionally involved family resulting from a second marriage to a widower which blended her three biological children with his three motherless children. There are eleven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren and she is, still, hands down, the person at whose house everyone wants to celebrate a birthday, wedding, movie premiere, art opening, or trunk show. She is affluent, generous, and actively participates in many cultural events —theater, cinema, the fine arts, ballet, museum exhibits —and contributes philanthropically to social causes and creative endeavors.

As long as I have known her, and despite her being involved in many vital activities and projects, she has always devoted a portion of every session to reviewing the current status of the children, grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren. Who is having a work-related success? Who is struggling financially? How can she help resolve tensions in her granddaughter’s marital crisis? Will she host the fund-raiser for a school for special needs kids?

“This ‘accounting’ of her flock

is a basic form of orienting herself,

in her family and in the world,

like a checklist of her own well-being.

Motherhood is at the core of her self,

from which many aspects of identity

and integrity radiate.”

Since Donald Trump improbably won the election, her sense of hopelessness, fear, and shock have intensified. She has always voted for liberal causes and leaders, contributed to political campaigns, and participated in events that represent her priorities and hopes. The day after Trump’s victory, she arrived at her session and burst into tears, expressing a profound sense of helplessness and concern for the well-being of those she will leave behind. Her children embody her hopes for the future and represent the values she has relentlessly strived to inculcate in them, especially care for the welfare of others, charitable giving, loyalty to each other, and participation in the world of ideas and actions. She now worries that two of her children, a writer and painter respectively, will struggle to make ends meet. Will the money she and her husband leave behind be enough to protect them? Who will help with private education funds for all the great grandchildren who will undoubtedly inherit the family’s dyslexia and other learning problems? As her future gets closer and narrower, her generative impulses are directed into those who will inherit her world. She is dismayed at the limits of her ability to protect and provide for them. As a person who has generally been able to turn desires into actualities, it is surprising and disequilibrating to feel her powerlessness. Aging brings many of these issues to the fore, and now they are heightened by an external reality in which humanitarian causes and individual socially conscientious impulses may be rendered impotent. Whereas earlier considerations of her children’s inheritances afforded a sense of peace and relief, she now fears their possible disenfranchisement. She also despairs about how less privileged and protected people will fare with increasing threats to reproductive rights, employment, equality for all social, racial and ethnic minorities, the environment, etc. Conservative regimes do not tend to foster the arts or encourage creativity.

“In the absence of these hopes and

commitments, we are left feeling

isolated, defeated, and despairing

about the future our loved ones will

inherit, and the present we must

ourselves occupy with a sense of

meaning and purpose.”

Narcissistic leaders do not tend to engage their constituents with the promise of what the leader can give so much as what the powerless individual has to gain by affiliating with the leader’s power and self-interest. At this time in her treatment, the patient faces the possibility of a much-changed and constricted world as she struggles to hold on to her characterological optimism and altruistic spirit. Aging and “running out of time”, in and of themselves, are challenges to the individual’s sense of purpose and standing in the world. In this final developmental phase, Erikson emphasized generativity, the satisfaction that accompanies the thought of passing on to those who follow one’s investment in life and both personal and extra- personal growth. As our own future shrinks, there is pleasure in imagining the lives that will continue after we are gone. There is contentment in feeling we leave our children a sense of belonging to an expanding web of relationships and connections, a sense of personal agency, and a desire to participate, in turn, in the world they will leave behind to their survivors. In the absence of these hopes and commitments, we are left feeling isolated, defeated, and despairing about the future our loved ones will inherit, and the present we must ourselves occupy with a sense of meaning and purpose.

On Inauguration Day, in the company of several intelligent and reasonably worldly women, I expressed my own worry about what will happen to our country under the leadership of Trump. Two women, in almost the same words, snapped back, “Get over it! He’s our president and we’ll accommodate!” I believe the challenge is to do more than ‘get over it’, but to ‘get into it’, actively engage in what this new era of constriction and intolerance will entail. In analysis, we rely on the safety of a secure frame, with its promise of predictability, reliability, and containment, to explore those parts of ourselves and our world that frighten us, beckon us, and cause us conflict, with the longer-term goal of mobilizing strengths in the service of a higher level of adaptation and freedom to inhabit ourselves more fully and creatively. Under similar conditions of containment, reliability, and concern, cultures can also thrive.

For our oldest citizens, the sense of outrage can be very acute as feelings of powerlessness due to external reality converge with diminishing physical, mental, and emotional reserves and the tightening grip of finite time. As clinicians we must be sensitive to the anger older patients may experience and encouraging of their search for meaningful outlets for it. Similarly, we must help them to balance those trends that move toward loosening the hold of reality as they face the incontrovertibility of their own death with opposing urges to continue to participate and make a difference. –

-

Janet Fisher is a Training and Supervising psychoanalyst and on faculty at IPTAR. Email: jfisher512@gmail.com

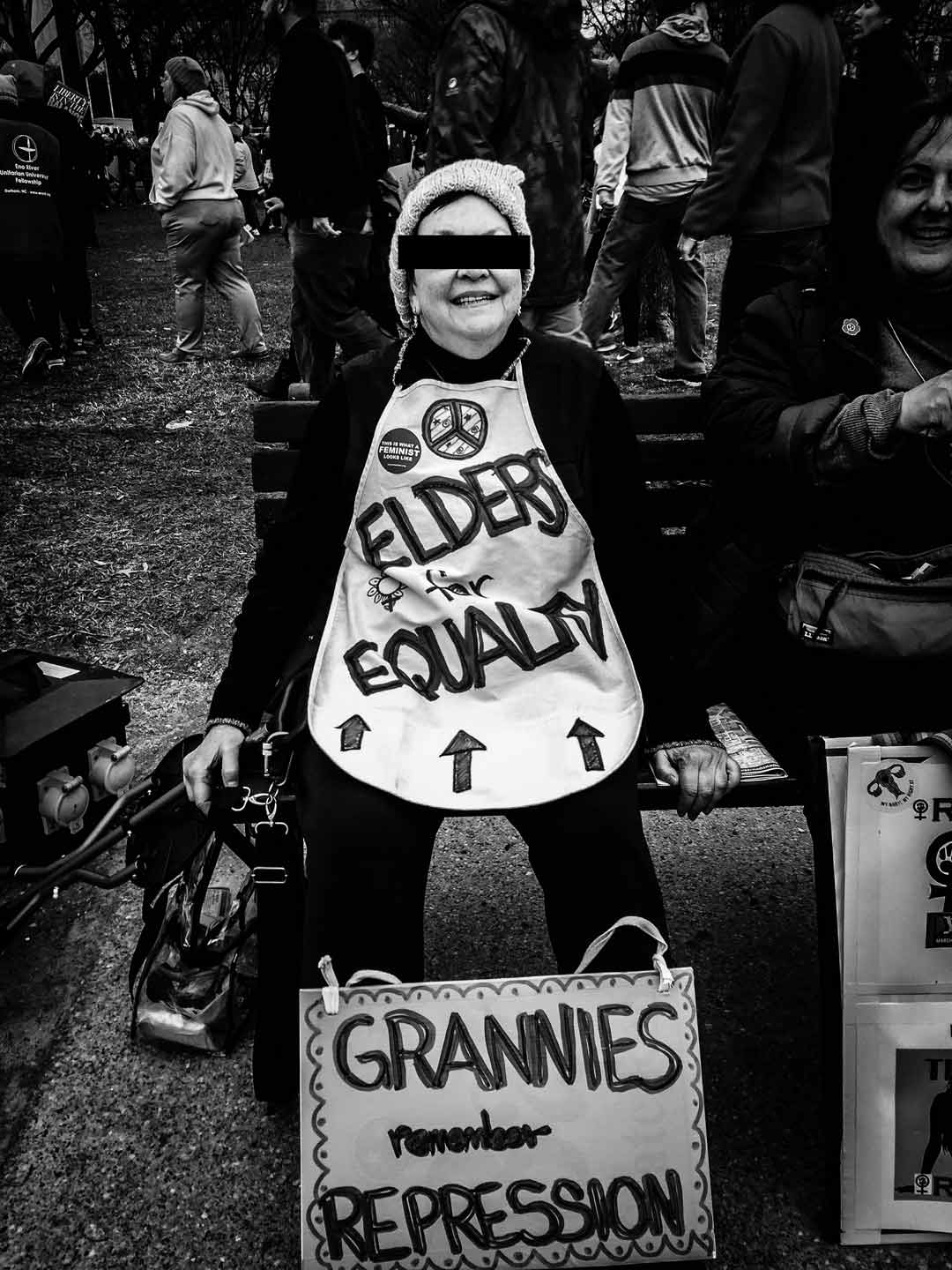

- Photo: ‘Elders for Equality’ by Diane Meier M.D. who founded and directs the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). Women’s March Washington D.C., 2017.

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |