COLLECTIVE DISAPPEARANCE

by Rocío Barcellona

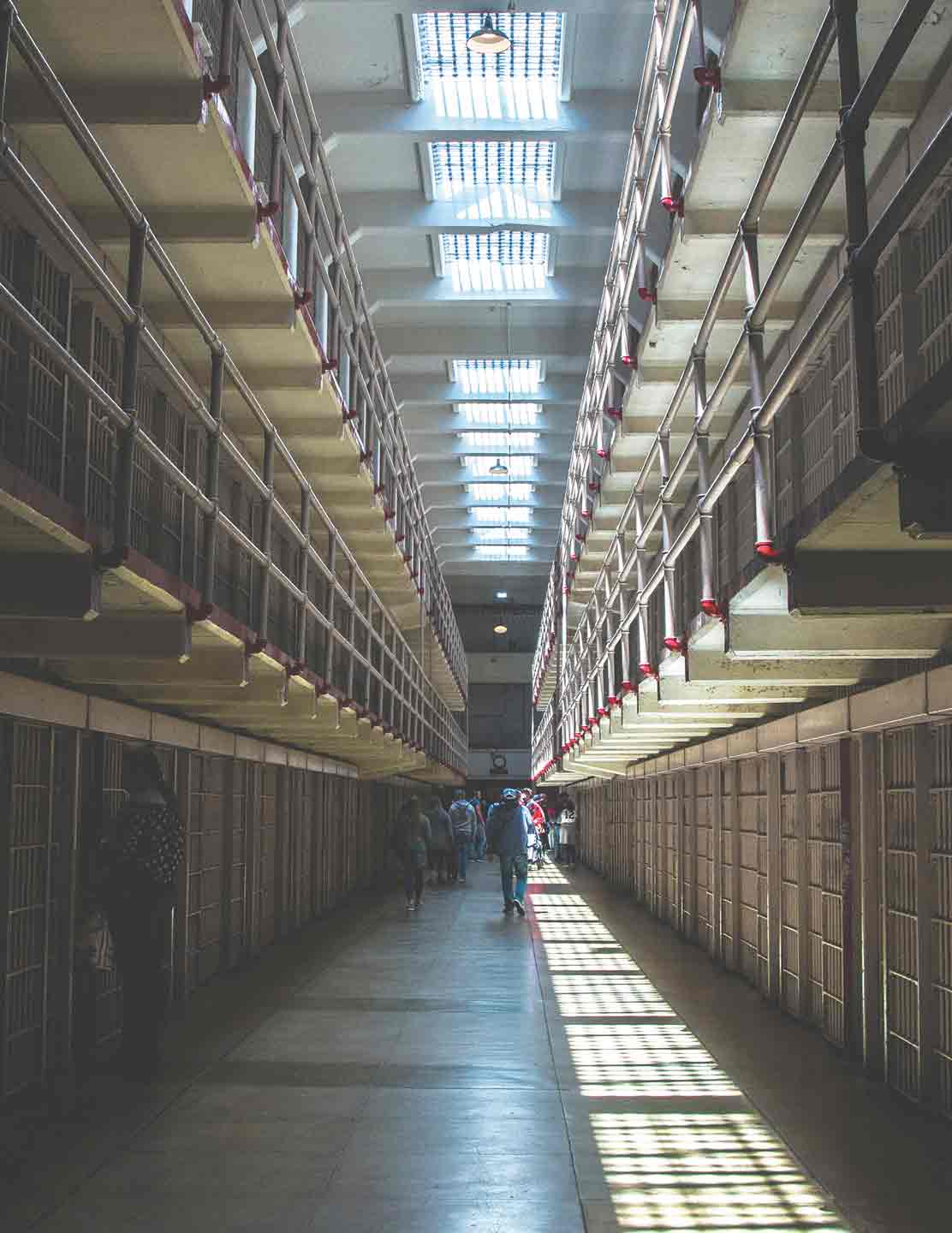

“The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.”

—Fyodor Dostoevsky

“You scare me,” he says.

“I scare you?” I reply, half-offended, half-confused, that I, a five-foot-tall woman, could scare my level IV inmate who lives in a maximum-security prison rife with violence.

“Where did you come from?” he asks.

“You lost me,” I say. “What are we talking about?”

He starts to tear up. “I can’t remember the last time someone treated me like a person. It scares me.”

I feel as if I’ve been punched in the throat. Being treated like a person is scary here. One must then recognize that one is indeed a person, which then makes one aware of the inhumane realities of this place. I thought I understood then. But as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, I got an even better understanding.

At first, we continued with business as usual despite reality indicating to us that we were deluded for doing so. Finally, some modifications were made to programming, but none really made sense. Some groups were allowed to run with fewer participants, until it was finally understood that they should not be running at all. High-risk inmates (who were designated as high-risk due to preexisting health conditions or age) were assigned to a “well quarantine,” which meant that they were to stay in their cells. This would have made sense if they were not, at times, housed with non-quarantined cell mates. Of course, this infuriated many inmates, who understood that this precaution was laughable at best. In addition, they were to “stay in their cells” but could go places, such as to the shower, the day room, the phone, none of which was consistently sanitized in between uses. Some of those inmates have even been allowed to continue working their jobs.

Essential workers continued to come in and were given little to no protective gear. Headquarters repeatedly sent us emails reminding us to clean but provided no supplies for us to do so. Initial instructions noted that protective equipment was “optional,” which I assumed to be a euphemism for “not consistently available.” At times, it has felt like a scavenger hunt, as workers look for clues about where protective equipment may be located and go on a journey to find gloves, masks, and any cleaning supplies available. “It’s funny,” I say to my friend, “how much the state has mastered the art of telling you that you are ‘essential’ and that ‘you don’t matter’ simultaneously.” My friend laughs. In here, we use humor to cope.

I bring up in a team meeting that if our inmates become infected, many will likely die. “You think so?” asks a supervisor in a nonchalant manner.

“We have over a thousand inmates considered to be at high risk. And I’m sure we ain’t got a single respirator!” I fire back.

She says, “I don’t know; you’re scaring me.”

I scream inside my head: You really haven’t thought about this? The truth is no one thinks about this. Prisons are built to be “out of sight, out of mind” places. As a society, we don’t want to see them, to think about them. Being confronted with the reality of our own humanity, or lack thereof, is too painful. Who wants to become aware of the fact that we lock thousands, millions of humans away in places where diseases can run rampant? Who wants to know that we provide inmates with little or no resources to mitigate this, to protect themselves? Who wants to admit that they think that prisoners deserve this?

As I talk to people on the outside, many argue for lifting the quarantine. “People can’t be stuck inside for that long. They go crazy,” someone tells me.

I can’t help but laugh. “Really?” I say. I want to ask them to repeat this statement out loud as many times as needed until they see the irony of making such a statement to me. I work in a place where, per the estimates I’ve heard, approximately eighty-five percent of people are serving life sentences. I am often struck, though no longer surprised, when confronted with how little people think about this. And when they do, they either don’t think of inmates as people or think inmates deserve these conditions. People are having a hard time staying in their homes, with their food and their comforts and their internet and their families…but, as a society, they have no problem sentencing someone to spend their life in captivity and deprivation. Am I the only one who’s angry? How many people will come out of this quarantine with the desire to change the conditions within corrections? To change the realities of life sentences? It’s a good thing I don’t run on hope.

As a psychologist, I become aware of the spaces we inhabit, between person and disappearance, marching toward and against erasure with our inmates. At times, our presence is the only witness to their presence. Watching that from outside makes me feel like a witness, a voyeur, and an invader. What a privilege it is to be a witness to the pain of existence in a place that seeks to strip you of your ability to be a being. How tragic it is to be a witness to our collective disappearance. The more they disappear, the more we disappear, the more they disappear. Who will hold on to us as we fight to hold on to them, as we fight to convince them to hold on to themselves in a world that does not care if they let go? How do we, the “essential workers,” hold on to our humanity and theirs in the face of such apathy? How do we continue to treat ourselves and others like human beings in places meant to dehumanize and break down people? How do we remain human? And most importantly, are we even human? ▪

-

Rocío Barcellona, PsyD, works in a maximum-security prison. As a clinician, she seeks to make space, to encourage autonomy, and to facilitate self-discovery, believing that the more we know ourselves, the less damage we do to ourselves and others. She doesn’t go to work to “fix,” change, or judge anyone. She doesn’t know what is best for people and cannot keep anyone safe or alive. She can only listen and promise not to run away.

- Email: mrb289@yahoo.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |