My Back-Alley Abortion

by Adrienne Harris

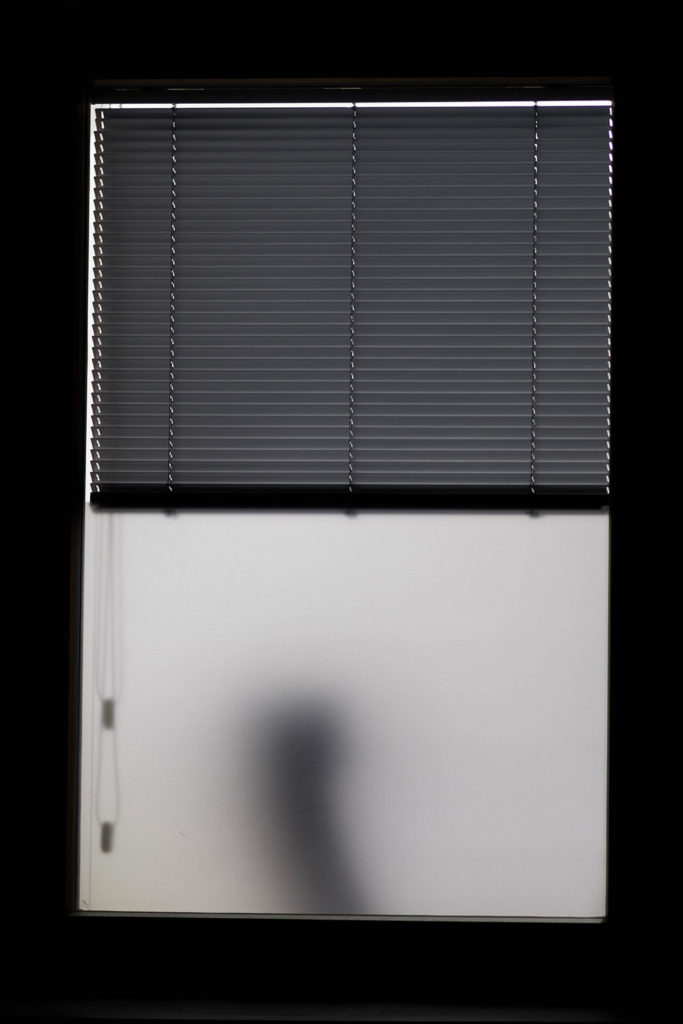

Let me bring you into the room. It’s a clinical operating room in a private office in midtown Toronto. It has a space to lie down. Other than that, the room is bare. I am tempted to use the word “barren,” which I think captures a fear I cannot articulate. All I can feel is how afraid I am. What am I wearing—a surgical gown? Perhaps just a slip and underwear. I remember already feeling shame and fear. I don’t or can’t really take in the specifics of my surroundings. I am terrified, shame-ridden, more singularly alone than ever in my life, though my life is not very long at this moment. I am nineteen, a sophomore at an Ivy League college, where one should surely be able to manage one’s life. But, at that moment, late-fall 1960, I have left my quite luxurious and sociable dorm room to come north to the city I grew up in, where an older woman friend—the only person I can speak to in any confidence—has put me in touch with a doctor. I say that so easily. Maybe really a doctor? Many years later I learned that this person did indeed have a medical license, but during that first encounter, I knew almost nothing.

When I called my friend to say I was pregnant, she was kind and comforting. She clearly knew what that meant or could mean. Been there. Done that. She took a very strictly practical stance, and she helped me find the right person for that moment of legal, moral, and psychological uncertainty. Or so I had to believe. So, I sit in the waiting room and then the operating room under the control of a man who is mocking, sneering, subtly but clearly insulting, and shaming. He does his work. No anesthetic, no language, nothing comforting is said or intended, no pain meds. I walk out of the room onto the street not sure I am viable or safe. I feel damaged and bad in mind, spirit, and body. The physical pain of the experience must be carrying the emotions. I cannot sort out if I should and will die, or if I have escaped some human female requirement for suffering.

Am I bad? Damaged? Lucky? All of the above?

My older friend takes care of me for a week, and I go back to college. I have a different life from the one that would have unfolded had I not had access to abortion, however terrifying. And through some mix of luck and biology, my experience at nineteen does not consciously or critically destroy or fatally disrupt a later history of fertility and family. Yet I am aware that the emotional cost has taken a lifetime to process. I don’t want to exaggerate, but that experience lived a virulent life in my unconscious. I think the criminality of that situation contributed significantly to feeling criminal. I feel it is important to speak about now, as abortion seems, with sinister determination, to be moving into criminalized spaces (inside one’s mind and in the world). In the decades since my illegal abortion, whenever I drove down that street in Toronto, I felt a stab of shame—mild, subtle, but inevitable. Consciously, I practiced consistent support for women’s freedom. Unconsciously, a slower, more insidious process took place.

But to go back to that room is something I still do reluctantly. Everything was at stake, and everything altered in that painful, frightening space. One odd remnant reappeared. Over a decade later, I am in Toronto with my family—my parents and my children. All seems easy. My father, his face oddly strained, asks to speak to me alone. He has had a call from someone in the police department. My name has turned up in the records of a man arrested for illegal abortions. My father looks anguished. I feel the world opening under my feet. I make up some story as to why I would have been in that person’s office. My father, I suspect, is relieved not to have to hear or say any more.

What discursive scene has been enacted? I feel the interwoven strands of hatred and fear of women and sexuality, of the haunting that accompanies action. But mostly I feel my intense commitment to erasure and refusal. Nothing happened.

And in a sense, that refusal, that denial holds to this day. Everything worked out. No one was hurt. I stay in control. Refusal, resistance, repression. In one sense, this is a story of the bad old days, when abortion was not a right but a theft, a crime, an erasure.

A number of years later, probably close to twenty-five—a quarter of a century—I take up reproductive rights activism. In a group called CARASA: the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse. We hold demonstrations, sit-ins. The Black women in this battle with us are inevitably more injured and harassed, and whenever we are arrested in the course of demonstrations, they inevitably get longer sentences and larger fines. At the sentencing after the arrests, the white women are sent to take care of the Black families whose protesting mothers are serving time in jail. I arrive at the house of one of the jailed women. Her children—four and eight, perhaps—await me. We shop; we go to the park. The older child is so grown-up, so parentified (a word I do not yet know), and he helps me care for his little brother.

But this neglect and loss sit in me alongside relief, enigma, and mourning. At the time, I was most conscious of shame and terror. Later I thought about the dangers I had not even dared imagine: death, sterility, never having or knowing that child or having the child come to a space of meaning.

I bring myself and my reader back to that room at this moment in a radically and dangerously changed world for women. Now that Roe v. Wade is dismantled, what will poor women and young women and women whose class, race, and situation limit massively what actions are possible do? The New York Times the other day had a picture of a young white, middle-class woman reflecting on the current (but surely endangered) possibility of taking medication—abortion by pills—to induce miscarriage. We surely know that whatever technology can generate, its availability will still function by class and caste and privilege.

I have relived that experience so many times in my imagination. This is the first time I write it down. Something of the return to the nightmare of illegal abortions requires me as a witness.

Because I could act and make my own determination about the outcome of pregnancy, I continued various forms of privilege: college, graduate education, a new relationship and marriage, a whitewash that at that time had something crucial to say about class and privilege.

I got to choose to keep the pregnancies I wanted to. My shame stayed hidden.

That shame-ridden scene in Toronto, now over sixty years ago, awaits many women in many difficult and dangerous situations. In thinking and talking about the destruction and dismantling of Roe v. Wade, the memories of that period of shame and fear came back. At a Zoom conference on abortion, a colleague, a woman of my generation, spoke of the history of reproduction and the times of “back-alley abortions.” I shuddered. The room I went to in 1960 was in a polished, upstanding, reputable medical building. Who knew the actual practices of the doctor I was visiting? Yet it was “back-alley,” covered up with veneers of legitimacy. But in the consideration of danger, legitimacy, and the shame so easily attached to female sexuality and embodiment, it was “back-alley.” As I reread this account, I have to notice that there is no trace of a partner, shared responsibility, or mutual care. I think that was true throughout that experience. My older friend stood by me, helped, contained, and comforted me, and was never judgmental. But it is clearly in retrospect an experience that was mine alone to bear and manage and work through. This must be part of my character but also, I think, part of the era. How do we go forward maintaining the deep capacity for supporting other women that feminism and the women’s movement gave us? How not to live always alone in a frightening and dangerous room?

That is one of my worries for the women, now three generations younger than me, who have an increasingly shaky access to means of being in control of their bodily, sexual, and reproductive lives. And as we learn, over and over, that danger falls unequally on women of different classes, races, social groups, and castes. We—all women—are again at the mercy of the “back alley,” but we are not equally vulnerable.

- Adrienne Harris, PhD, is faculty and supervisor at the New York University Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis. She is on the faculty and is a supervisor at the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California. She is an editor at Psychoanalytic Dialogues and Studies in Gender and Sexuality. In 2009, together with Lewis Aron and Jeremy Safran, she established the Sándor Ferenczi Center at the New School for Social Research. She coedits the book series Relational Perspectives in Psychoanalysis with Lew Aron, Eyal Rozmarin, and Steven Kuchuck.

-

Email: adrienneeharris@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |