Hallowed Spaces

I have been thinking a lot lately about what it is that makes for a sense of community, of being seen, of being accepted and appreciated, of being part of something, taken in and looked after.

As I think back on my life, I have most felt a sense of community in the least likely places. I was raised abroad, and all through my growing-up years, I often found myself feeling foreign and out of place when I set foot in my passport country, while overseas, at odd moments, in places I had the least right to do so, I would feel accepted and taken in. This experience has repeated itself throughout my life.

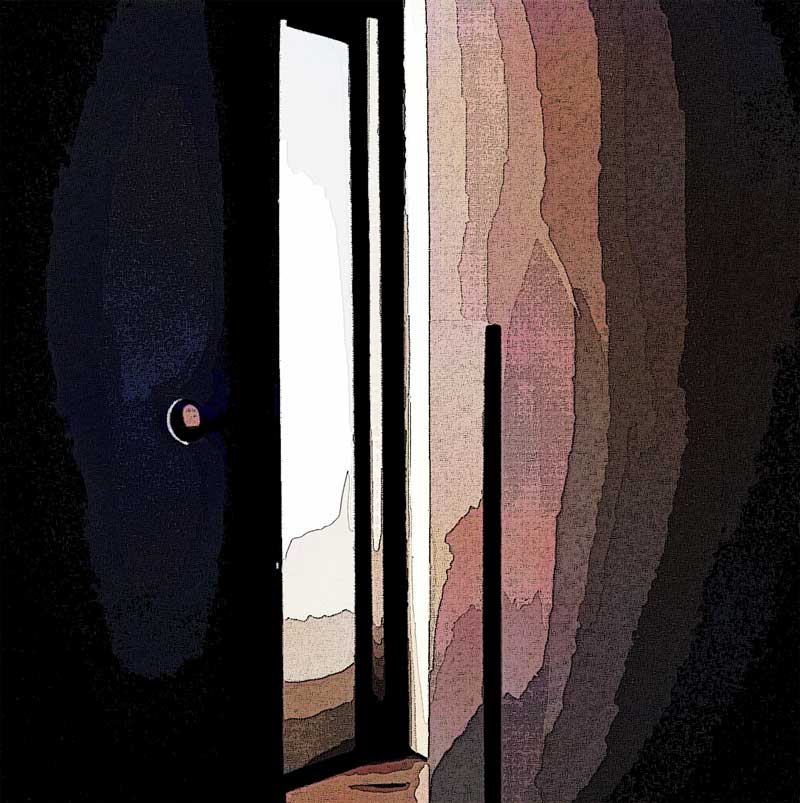

One moment that stands out for me is the dark, bone-chilling moment in 1978 when my boyfriend and I arrived at dusk at the remote field station in Patagonia, where we were to study whales for the next eighteen months. The caretaker of the camp was nowhere to be found, and the house, set on a vast, empty bay in the bleak southern Argentine steppe, was locked tight. The sea was roaring, the winter wind was gusting madly, we were instantly chilled to the bone, and we had no idea what to do. We had next to no Spanish, were dressed in ragged hippie jeans, and possessed of only the ignorant, blundering willingness of youth. After half an hour of wondering which thornbush we should sleep under, a truck arrived from over the cliff. A wizened Patagonian couple who knew us not from Adam or Eve—or perhaps only as Adam and Eve—magically stepped out of the old Ford. The old man, in an ancient beret and thin jacket, with quiet, self-assured dispatch, built a fire in a ring of thornbushes and set upon it a slab of mutton pulled from the truck. His wife, patting us and cooing soothing phrases we could barely understand, punctuated frequently with “pobrecitas,” for “poor little ones,” then handed us sizzling morsels of meat set on hunks of old “campo bread” from a burlap sack, as the man shared with us swigs of wine from a seasoned leather bota. After assuring themselves that we were fed, the sparkling-eyed old couple then squeezed us into the cab of the truck with them and drove us for half an hour over a rough dirt road to their home. Once there, in the tiny abode that consisted of a kitchen and a bedroom, they ushered us into the one additional room: a guest room possessing two simple cots. In that hallowed, lightless space, the lovely old woman, cooing her motherly chant, motioned us to climb into the beds and tucked us in.

That night, though the wind howled and we were utter strangers to our hosts, and though our only communication, really, was through the body, I felt utterly and thoroughly seen, accepted, embraced, and looked after. (Loved.) I felt, immediately, “in community.”

Over the course of the next months, we got to know Don Pepe and Dona Sara well through that great human gift that adds to the sense of connection begotten via the senses. Through language, we traded with the couple stories of our lives and exchanged our perspectives on the world, and as we got to know other warm Patagonians, my initial sense of community deepened.

In some ways, that experience, and the many experiences I have had, of often feeling utterly alone in the world and then utterly cared for, have shaped, without my awareness, the work I have done throughout my life. Trained as a social worker and psychologist with a specialty in cross-cultural human development and become, by pure need and instinct, also a writer of literary nonfiction/memoir and personal essay, I have found myself, for the last three decades, using the teaching of writing to foster a sense of community. Offering a space for people to simply express their feelings and pour their experiences onto the page, to share their heartfelt tales, and to read and bear witness for one another is a very simple and magical thing. Love tumbles around the room; people hold hands in the face of what life casts us. Just placing one’s experience outside one’s own body is mysteriously transformative—sometimes in tiny and sometimes in enormous ways. On the page, you can see yourself and what you think more plainly. The experience of writing in a nest of safety, where participants write simply for the sake of self-expression, in a context free of competition and judgment as to the “quality” of the writing, where there is no seeking of recognition or publication, offers people a rare sense of comfort and freedom. The other great, great boon of these workshops is the wonderful sense of community and connection that results. Writing and sharing writing with others in an atmosphere of witness, solidarity, and support is deeply confirming. We gain a deep sense that we are all united in this human odyssey.

-

Sara Mansfield Taber is the author of the new memoir Black Water and Tulips: My Mother, The Spy’s Wife and the award-winning Born Under an Assumed Name: The Memoir of a Cold War Spy’s Daughter. She has also published two books of literary journalism and the writing guides To Write the Past: A Memoir Writer’s Companion and Chance Particulars: A Writer’s Field Notebook. Her many essays and reviews have appeared in publications such as the American Scholar and the Washington Post. A practicing social worker and psychologist with a specialty in cross-cultural human development, she has coached writers and led writing workshops at universities and literary centers and for a wide variety of communities for the past three decades.

-

Email: smtaber@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |