UNDERSTANDING, CHARLOTTESVILLE

by Jared Russell

For the previous issue of ROOM, I contributed a piece that argued against the idealization of tolerance, diversity and understanding that I see so many in the psychoanalytic community currently engaged in. I’m aware that some readers, including some who attended the public conversation between Elizabeth and me at IPTAR in June, thought I was arguing against tolerance, diversity and understanding as such. Of course this was not the case. What I had actually argued was that there is nothing intrinsically virtuous about these ideals, and that the sophistication of an analytic approach lies in being able to discern when they facilitate integration, and when they embolden the symptomatically divisive status quo.

When President Trump, following the events in Charlottesville this summer, made statements that there were some “very fine people” among the torch-bearing white nationalists who demonstrated, and that those who demonstrated and those who protested shared equal responsibility for the murder of Heather Heyer, he expressed exactly that position I had argued against. The notion that all gestures of defiance and refusal are inherently based on an inability to understand or to “see the Other” belongs to an effort to deny all genuinely political reflection. At the heart of such reflection is the fact that

there are no attempts at inclusion that do not generate some form of exclusion. It seems to me that both our political fate as a people and our professional fate as analysts today turn on whether we can witness and assume responsibility for this fact.

Many of those on the right imagine that they demonstrate intellectual prowess in arguing that, by insistently denouncing hateful speech, those on the left express hypocritically their own intolerance and tendency towards fascism. Unfortunately, to the liberal mindset this charge tends to be confounding and therefore effective. Political debate in America has become so insipid that we seem no longer capable of distinguishing between the terms “left,” “liberal” and “Democrat,” or between the terms “right,” “conservative” and “Republican.” Instead, we are given two teams to root for, two channels or flavors to choose between, and we imagine that our identity issues from the choice we make and the consistency with which we make it.

The idealization of tolerance and understanding supports this naive, self-destructive fantasy. Recall that the Civil Rights movement was not built on efforts at trying better to respectfully understand proponents of segregation and discrimination. Today we are in a different historical moment. Trump symbolizes the fact that someone can be born rich yet still believe they are essentially and truly a victim.

We face a situation in which those who are in power have learned to imitate the voices of those who have historically, actually been oppressed in order to advance their own self-interests.

I worry that, out of fear that somewhere, someone’s feelings might be hurt, psychoanalytic communities are cultivating such a pathological fragility among their members that they will be unable to respond to this situation, and that this failure will actively contribute to the demise of our discipline.

Freud spent a considerable amount of time diagnosing what he believed to be the great truths about what it means to be human: that we are irreducibly motivated by the pursuit of pleasure; that we insistently substitute fantasy for reality; that we are viciously selfish to our core, driven to destroy what we love. If this were all Freud had done we could safely agree with his critics that psychoanalysis belongs to the dustbin of history. In contrast, however, by inventing a technique of clinical intervention that is not standardized and universal but that is capable of adapting itself to the singularity of each patient’s individual discourse, Freud left us to contend with a practice that challenges any essentialist definitions of our humanity.

It has always seemed to me that our field hopelessly struggles with the contradictions that its practice exercises over and against its theories. Each psychoanalytic “school” organizes itself around what it takes to be the fundamental human truth: that we are biologically driven; that we are interpersonally relational; that castration is bedrock; that the breast is primordial; that we must contain our aggression; that we crave loving recognition; and so on and so forth. I’ve yet to find an institutional form of our discipline organized around what it is that we’re confronted with every day in our clinical work: that people are haunted by an essential lack of essence, or of any ultimately definable identity; that there is no given truth about our humanity beyond what we are able creatively to invent for ourselves; that life is as meaningful or meaningless as we are capable of allowing for, and that it is precisely this capacity that human beings are deprived of today in being submitted so brutally to an industrialized global economy that demands its subjects appear as transparent and exchangeable as its products. I believe that it’s against this background that psychoanalysis demonstrates not only its therapeutic effectiveness but its intrinsically political orientation as well. Where a subject engaged in uncensored free association is met by another engaged in evenly-hovering neutral reverie, what’s suspended is the demand that identity be immediately comprehensible, fixed, available in ways that can be rationally, logically calculated. Nationalism, racism and all forms of fundamentalism —religious and otherwise— are efforts to refuse precisely this kind of experience and the anxiety that it necessarily induces.

This anxiety was articulated with astonishing clarity by the enemies of adult intelligence who marched on Charlottesville this summer, who incited and who alone are responsible for the violence there.

For a moment, the crowd held itself together in solidarity with the chant, “You will not replace us.” When these words were quickly dissimulated, devolving into the typically juvenile anti-semitism of the alt-right (i.e., “Jews will not replace us”— which served only to distract from what had been said and to re-project the intended macho image), this seemed to indicate that an unexpected instance of vulnerability had just emerged. The crowd had not chanted, “You will not defeat us”— which would have been an altogether different kind of challenge— nor had it chanted, “You will not intimidate us”— which, again, would have spoken to something else entirely. This particular turn of phrase— “You will not replace us”—resonated for me both as a currently disillusioned subject of democracy, and as a practitioner in a field itself in such a comparable state of disrepair. As these words echoed across various news reports over the days that followed, I thought of every patient who had abandoned treatment just at the moment when tremendously positive changes in their lives had begun to occur. I thought of every patient who entered analysis with some variation on the demand, “Cure me of my symptoms, but don’t change who I am.” And I was reminded that resistance is a concept that belongs centrally both to psychoanalysis and to politics. The parallel I am drawing is not between our patients and our enemies in Charlottesville, but between our enemies and the dynamically unconscious claim of the symptom itself, as against both patient and analyst alike: “You will not replace us.” Delivered as an interdiction, this statement at the same time describes the foundation of any community, the very possibility of all working alliances: the cultivation of an “us” or a “we” over and against a “you” or a “them.” Any attempt to avoid this gesture is an attempt to disavow the experience of the political itself. It’s incumbent on us to accept the terms of this demarcation, and to provide the only possible response: Yes, we most certainly, absolutely will, because that is precisely what we have dedicated ourselves to doing, by practicing psychoanalysis.

-

Jared Russell is a psychoanalyst and on faculty at IPTAR. His most recent book is Nietzsche and the Clinic (Karnac 2016). Email: jknightrussell@gmail.com

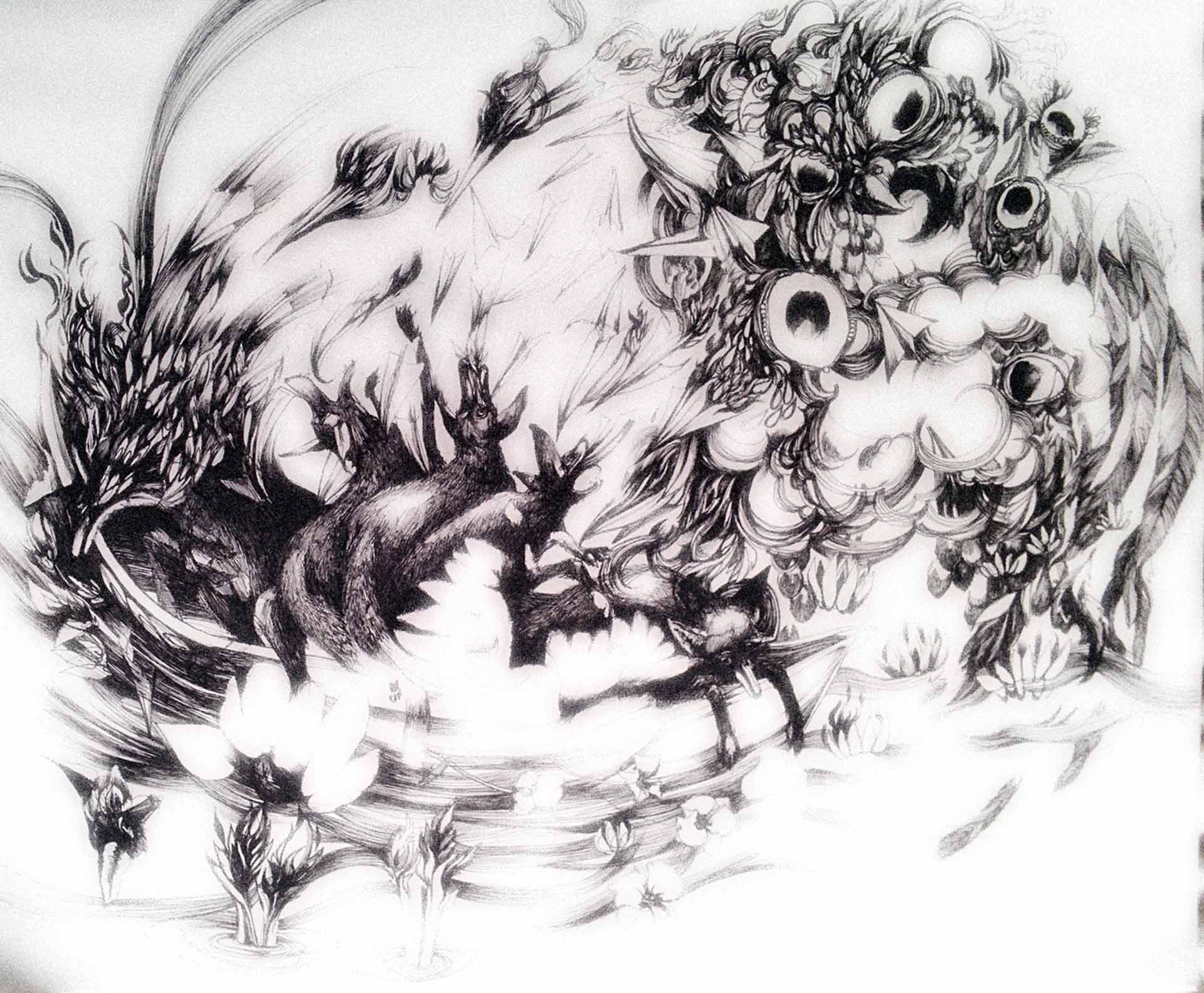

- Sarah Valeri is an art therapist working with children with visual impairments and diverse developmental experiences, as well child survivors of trauma. She is a Candidate in the IPTAR’s Child Analytic Program (CAP). Sarah is an internationally exhibiting artist.

- Also read: Understanding, Democracy by Jared Russell

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |