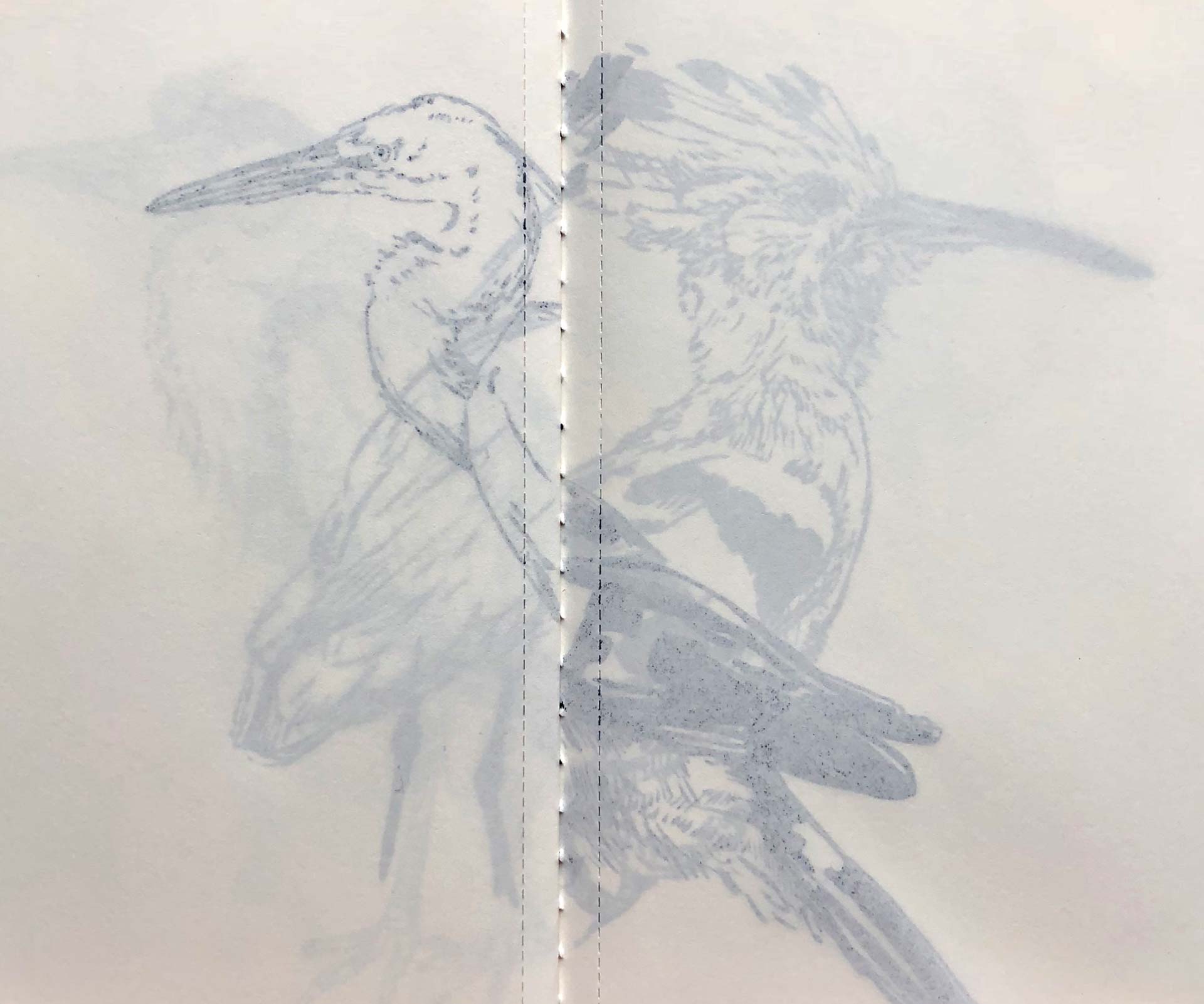

A BIRD

by Enrique Enriquez

Click on the image to open the gallery

These days, it has become clear that the only furniture that counts is that of the innermost dwelling. Therefore, “home” must be no more than the clearing in the forest described by Spanish philosopher María Zambrano:

The forest clearing is a center into which it is not always possible to enter; from the edge, you look at it and the appearance of some animal tracks does not help to take that step. It is another domain that a soul inhabits and guards. Some bird warns and calls us to go wherever it goes by marking a trail with its voice. And it is obeyed; then nothing is found, nothing that is not an intact place that seems to have opened in that single moment and that will never happen like that again.

And the fear of ecstasy makes its visitor flee from the living translucency of the forest clearing, thus becoming an intruder. And if he enters as an intruder, he hears the bird’s voice as a reproach and as mockery: “you were looking for me and now, when I am finally propitious to you, you return to that place where you cannot breathe.”

In Zambrano, we hear the echo of Isaac Luria. The bird’s voice slashes passages in the air, it opens space. That forest clearing, bounded by the twilight of our own umbrage, is the walled garden of paradise for whose memory we feel a deep nostalgia. This is not a place but an instant to which we return, or we try to return, continuously, and just when we remember the path, it is precisely memory that takes us away from it. Memory is a vector that derails experience and then throws us out of that moment empty of mirrors. This is how we know that this moment is not accessed through liturgy, that is, through the language of the other.

It is important to make the distinction between the languages of contemplation and those of action. The language of the birds is a contemplative language. It delivers its messages directly, the meaning of which disappears; it ceases to be understood as soon the stimulus ends, that is, once the bird is silent. Contemplative languages are languages of direct experience, languages of “what is.” The occurrence of such language is equivalent to that of dreams in the sense that it paralyzes the physical body while agitating the subtle core. For contemplative languages to have a foothold in the world, we must translate them into languages of action. Any mother tongue is precisely a language of action, the lingo through which we operate our reality. A contemplative language establishes the field where we avail ourselves of our own language of action.

The clearing is a glint, that moment between the language of contemplation and the language of action. The essence of being human is our ability to trip ourselves up.

“The other” is not only the predecessor that imposes a ceremony on us but ourselves a minute ago, the one that, holding on to self-awareness, cannot breathe in the space that the bird opens with its song. The paradox is in returning to a place of which we have no memory and for which we nevertheless long. That would perhaps be the definition of the future, but only if the future is the spot where things are named for the first time, and this name is imposed with enough gentleness that it does not completely trample what is named. Because to name is to breathe life into things—this would be a place that only exists for an instant and on whose endurance we depend, as in a heartbeat, as in breathing.

If by following the bird’s voice we return to paradise, then we will say that the bird’s voice is paradise, another garment for the laughter of the madman, a garden from which we are expelled as soon as we realize that we are in it. That is the true state of grace, the fall that pledges a return. The only way to avoid this exile would be to prevent words from sprouting in us. That is, to stop being human. To name the garden is to be cast out of it. We dare this orphanhood because of the imperative to tell others about its reality and because, from that momentary loss, we understand that this state we long for is our true home.

All my best, Ee.

-

Enrique Enriquez is a New York-based Venezuelan poet. His work with the Marseilles Tarot breaks new ground intellectually and artistically.

- Email: enrique.eenriquez@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |