DISORDERED

Click on image to open the gallery

Disordered was a collaborative, participatory street art project designed to destigmatize mental health challenges like depression and anxiety, and reframe health as a societal issue. The project took the form of conversations, stickers, signs, and a mural in public spaces around New York City. Through a combination of social practice and guerrilla strategies, Disordered intervened in public places, creating a space for personal interactions about the connections between mental health challenges and societal issues. It pushed ideas about how our history, culture, political, and economic systems affect our health in order to inspire personal, social, and political transformations.

Throughout this project, I used “mental health challenges.” rather than the medical terms “mental illness” or “mental disorders,” as a political statement. From the beginning, I wanted to draw a distinction between conventional ideas about “mental illnesses” and call into question how we think about health, illness, and disorder. Furthermore, I wanted to raise the questions “How do we define health?” and “What is disordered in our society?” and connect the answers. The name of the project, Disordered, emerged from this position, insisting on a collective challenge we all share.

The issues surrounding mental health are important to me because I’ve seen how these challenges and crises affect my students, friends, and family members, as well as myself. There are a number of issues on both sides of my family including eating disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders. Various family members have been hospitalized, institutionalized, and at least one who I know of completed suicide. My mother has been on medication for bipolar disorder as long as I can remember, and so I grew up in fear of developing a mental health problem. It was not until my midtwenties that I experienced my own major depression. I learned how my mental health is inextricably tied to my physical, social, and spiritual health. It took years to work my way out and learn a new way of being. Through this personal process, I have grown not to feel ashamed of my depression and anxiety. In an effort to change public perceptions about mental health and offer an alternative message, I wanted to share what I have learned and encourage others to share their stories.

I started this project shortly after Trump took office. His campaign promise to “make America great again” unleashed unbridled fear and anger for many people. I noticed that many people in my life who live with mental health challenges were destabilized and retraumatized by his assault on the rights of women, immigrants, people of color, people with disabilities, the LGBTQ community, and the Affordable Care Act. Essentially, the most vulnerable people in our society are now experiencing even more anxiety than usual. Yet, the unease we are experiencing goes beyond the most vulnerable. People who have been comfortable in their lives were shaken all of a sudden by Trump’s victory and what it implied for our country. News outlets from NPR to CNN began reporting on increased depression and anxiety as early as February 2017. A psychiatrist penned an article for Psychology Today in April 2017 titled “How to Cope with Trump Anxiety.” If we look around, it is not too difficult to see that the United States is experiencing a mental health crisis, which is very much related to our social and political crisis.

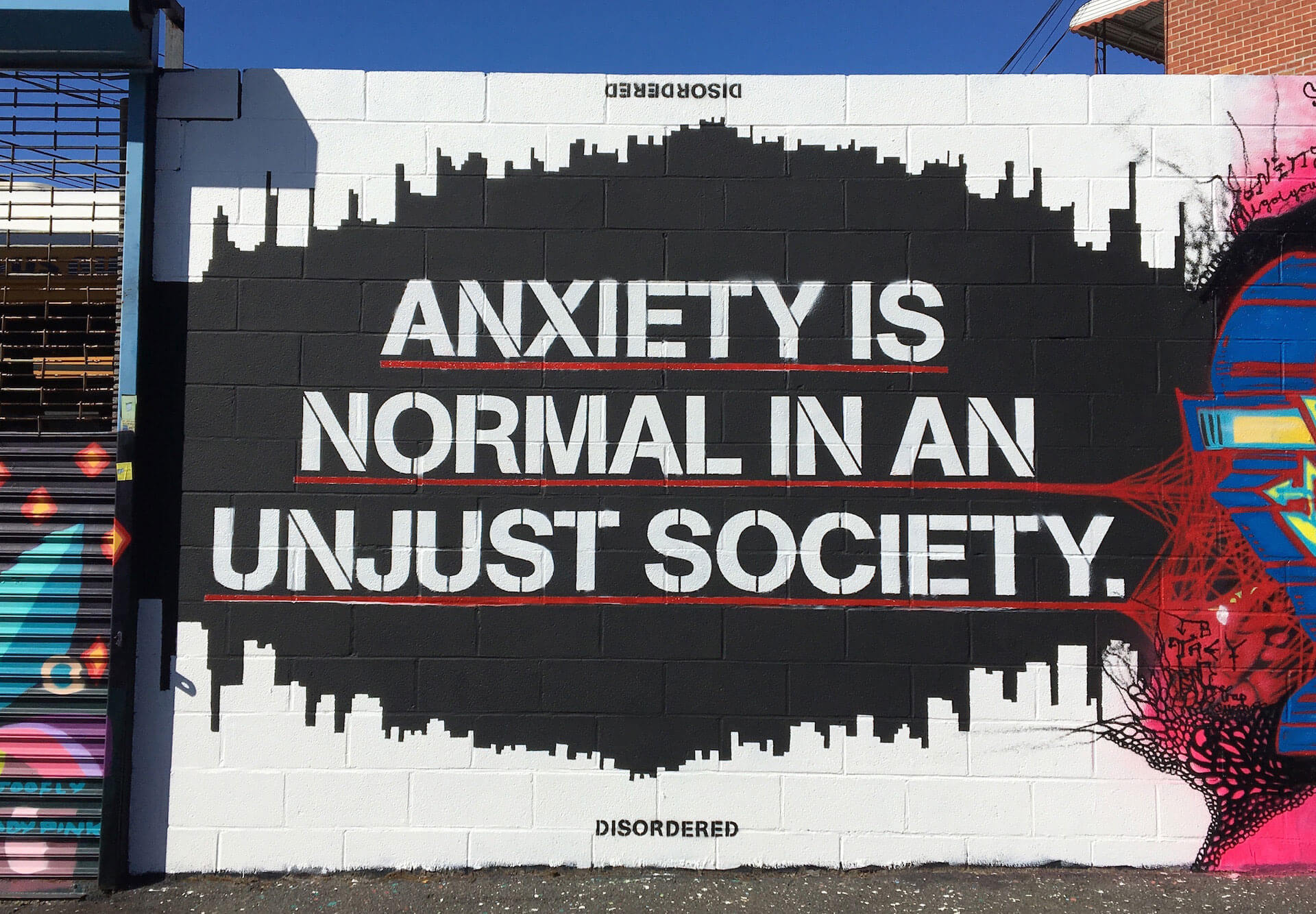

I started the project in the spring of 2017 by forming a steering group of about 20 people called the Disordered Project Team. Together, we designed and held three pop-up installations in public parks, during which over 100 people passed by, talked to us, took a sticker, made a paper sign, added a thought to a sharing board, or signed our email list. After the pop-ups, we chose the strongest and most provocative thoughts from the public participation to reproduce on metal signs, vinyl stickers, and eventually, a mural. In the fall, over 20 metal signs were installed in Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Astoria. Fifteen hundred stickers were printed and have been liberally affixed and distributed to all who wished to participate in spreading community-sourced messages about mental health and society. In the spring of 2018, we painted a mural as part of the Welling Court Mural Project, which consists of over 150 murals over several city blocks in Astoria, Queens.

During the pop-up phase in the summer of 2017, conversations frequently revolved around shame associated with depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues. In her TED talk, Brené Brown, who studies human connection from a social work perspective, found that shame, which she describes as “the fear of disconnection,” is the thing that destroys interpersonal relationships and social connection. To fight shame, Brown says we need to fully embrace vulnerability as a part of being human. She asserts that vulnerability is emotional risk, or in other words, courage. Brown adds that we have to talk about shame because empathy is the antidote to it. Face-to-face interactions were integral to Disordered due to the subject matter. Talking about mental health normalizes and destigmatizes it, and having these conversations in public as participatory art made this serious topic approachable and even a little fun. Many people made themselves vulnerable by talking about mental health with us and sharing their thoughts on our paper signs.

The connections between lacking mental health care, self-medication, law enforcement, and incarceration surfaced on the sharing boards during the pop-up phase. I wasn’t too surprised by this, since police brutality against people with mental health issues was in the news during the life of this project. In July, The Intercept released an article about the Chicago Police Department’s use of SWAT teams to respond to suicide attempts and mental health episodes over the last five years. In 2012, the city of Chicago closed 12 of its mental health clinics and privatized the six that remained. Since 2013, CPD dispatched SWAT teams over 38 times for mental health incidents, which escalated the crisis and increased the likelihood of a lethal outcome. In New York City, two black men in their thirties, Dwayne Jeune and Miguel Richards, were shot and killed by the NYPD in July and September of 2017. According to the Washington Post, one quarter of the 874 people shot and killed by police in the United States in 2017 were dealing with a mental illness.

In my research I found that oppression, including racism, sexism, patriarchy, ableism, heterosexism, etc., has been shown to have negative effects on the mental health of its targets. Studies have shown how psychological and political acts of oppression take place on various levels, including intrapersonal and interpersonal (via social group), state, and internationally. The asymmetrical power relations of oppression can occur through a number of identities and intersections (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, class, ability status). Research has shown how social group oppression can become internalized oppression, which has been linked to lower self-esteem, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, risk-taking behaviors, body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and somatic symptoms. Studies have also demonstrated that discrimination-related stress increases blood pressure, which is linked to increased mortality. Discrimination-related stress also raises cortisol levels, which is associated with obesity, depression, decreased immune function, cancer, and death.

I believe that in the United States a very large part of our suffering and worry has been created and cultivated through a history of individualism, capitalism, racism, and other forms of oppression and inequality. In other words, I believe that priorities are “disordered,” and this greatly affects our well-being in a negative way. I believe that thinking critically about health and society can not only help us to feel better, but can also help us deconstruct harmful systems and build sustainable supports for humanity.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation does research, funds programs, and advocates for health equity and a culture of health. In order for all people to have equal opportunity to health, the RWJS suggests we must work on environmental health (quality housing, access to healthy food, safe places to exercise); disease prevention and health promotion; reducing health disparities related to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status; and addressing social determinants of health (ensuring people have good homes, schools, and neighborhoods).

Ann Cvetkovich’s book and corresponding project Depression: A Public Feeling, develops a case for “political depression,” a state in which tactics like direct action and critical analysis don’t help us feel any better about the state of the world. Cvetkovich’s project sought to embrace negative feelings in order to generate hope needed for political action. She suggests that the unresolved traumas of our past, combined with the slowness of change, make it hard to acknowledge the emotional effects on our everyday life.

Kriss and O’Hagan describe political depression as an “interiorization of our objective powerlessness in the world”:

Political depression is, at root, the experience of a creature that is being prevented from being itself; for all its crushingness, for all its feebleness, it’s a cry of protest. Yes, political depressives feel as if they don’t know how to be human; buried in the despair and self-doubt is an important realization. If humanity is the capacity to act meaningfully within our surroundings, then we are not really, or not yet, human.

So how can we be human again, change things for the better, and truly address the causes of our suffering? Based on my research and interactions throughout this project, I believe it will take a multifaceted approach from as many different angles and levels as the sources of oppression and trauma in our society. This means fighting oppression internally, between persons, in our communities, and in larger arenas if we are to become fully human.

Over the entire Disordered project process, I learned that there is a huge need to talk about mental health in our society, especially in the context of social justice. Making myself vulnerable and taking risks was essential to the success of this project, in both a personal and practical way. I had to practice asking for help. I had to rely on the Disordered project team. This experience assured me that we need each other and that we need to work at being human if we want to overcome any of our many obstacles.

Disordered opened up the discussion about how mental health is a societal issue by intervening with unsanctioned art in public spaces. Adding our community-sourced messaging to the visual culture in New York City was an act of resistance against the silence and stigma around mental health challenges. Disordered put prosocial messaging in the streets to spread a new way of perceiving mental health and social justice issues. I believe that we must first imagine other realities in order to shape them. So, we interrupt the chaos of everyday life with expressions of the collective on stickers, signs, and a mural, to advance the ideas of ordinary people, who reject shame, promote dialogue, and inspire transformation. ■

-

Rachel Brown is an educator and interdisciplinary media artist. She is currently an adjunct professor at NYU and works for Mouse, a youth development nonprofit that believes in technology as a force for good. Since 2014, Rachel has been a member of The Illuminator, a political projection collective based in NYC. She has an MFA in integrated media arts from Hunter College (CUNY), and is an avid cyclist, yogi, and wanderer.

-

Instagram: @oikofugicrchl

-

Email: info@wanderingarrow.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |

![Genesis, 2024 [Detail]](https://analytic-room.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/HQ27-TL20896S_Tau_Lewis__title_TBC__small_figure___2024_6_high_quality-110x80.jpg)