BETWEEN THE LINES

by Gabriel Heller | Photo by Jakayla Toney #BlackLivesMatter protest in New York, USA.

We can all—or most of us—agree on the existence of a thing called structural racism. But can structures have a life of their own, independent of the people inside them?

One premise of a democracy is that there is an active line of connection between the whole and the part, that society and psyche shape each other in a meaningful way.

In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, it seems many white people are in a rush to prove their wokeness. To show they’re on the right side of history. Maybe some good can come of that.

But what to make of the disparity between our knowing language of concepts and analysis and the unknowing, ceaseless, subterranean language of fantasies and feelings?

A paradoxical question: In my way of using language, what gets lost to conscious examination?

More and more, I find myself aware of how speech can function as a smoke screen, motivated by a need to disavow my own embeddedness. More and more, it’s that problem of embeddedness that I keep coming back to—how my own mind is intimately bound up in the fabric of this American sickness.

What is the line that connects me to the lynching of George Floyd on a Minneapolis street? How is the flow of my most private thought and emotion, fear and desire related to a systemic pathology that is so easy to decry, and yet so seemingly impervious to our knowing discourse?

The forces of power, the forces that perpetuate inequality, that deny access, circumscribe difference, contain it as one might seek to contain a threat, are not outside us.

White supremacy, among other things, is a costly defense structure. It is designed to protect power and ward off fear. But the defense is full of cracks and always has been. The various forms of economic, cultural, and social segregation that are intended to guard against the eruption of white anxiety only deepen anxiety, as they deepen black despair and black rage.

Before I was eight years old, I’d been at school with almost all white kids. Then, for the first time, I was in school with black kids. I didn’t know anyone at my new school, and I was very anxious. My heart beat fast on the playground.

There was a boy named Earl whom I admired and wanted to be like. I liked how he carried himself. His body seemed to contain a power that I wished I had. I liked how he talked, and I tried to bend and modulate my voice to sound like his.

No matter what I did, there was still a gulf between us. A wide, charged space that filled with fantasy.

Every Wednesday, I went for swimming lessons at Medgar Evers pool. I had no idea who Medgar Evers was. In my mind, Medgar Evers was just the name of a swimming pool.

One day I saw Earle at Medgar Evers with his dad. After I finished my lesson, we shot around at the basketball hoop set up on the edge of the shallow end. His dad, who showed me how to hold the basketball when I shot, had a friendly laugh and wore a thick gold-link chain around his neck. Earle and I slapped hands when it was time for him to go. “Maybe we’ll see you here again,” his dad said. I felt like Earle and I would be friends now, because I had spent time with him and his dad, but at school there was still a gulf between us.

This was in the mid-eighties in Seattle, which is now a city full of lattes and gourmet food trucks and legal weed stores, a city flooded with Amazon money, a very white city. When I was growing up, it was very different from the way it is now. Of course, white people ran the show, like they do now, but it was also a very non-white city, and a very segregated city.

I went to middle school right on the border of black Seattle and white Seattle. We were in class with each other and at assemblies and school events, and we played sports together, and yet the gulf was always there.

The recession of the seventies, which included massive Boeing layoffs, had deepened a sense of misery in the ghettos that had been managed and maintained through very careful, deliberate government policies. By the late eighties, LA gangs had spread up the west coast. Crack cocaine was everywhere.

Sometimes kids would come to school with the silk-screened face of some other kid on their sweatshirt, and below the face three letters: R.I.P. At first, I didn’t know what those letters meant.

The street I lived on was so quiet. I would imagine the wood-frame houses were asleep. Tall evergreen trees surrounded the sleeping houses, looking down, bearing silent witness.

A white woman I work with recently spoke to me about what the Black Lives Matter protests she had been attending meant to her. She spoke in an impassioned but largely abstract discourse.

At one point, it emerged that growing up, she never knew any black people. Until she was in college, she had never interacted with black or brown people, except when they were serving her. But now she had many friends of color, she said, and she was grateful for how they’d opened her eyes.

It occurred to me that my experience was different, almost the opposite in certain ways from hers, that starting in college, my world became whiter and whiter, as if I were in a rush to take flight. In New York, the most diverse city in the world, I so often find myself in almost exclusively white spaces.

White silence equals white violence, she said, and the language she spoke—had learned to speak with conviction and eloquence—seemed to offer a solution, a way out.

A world of clear lines.

But who grows up in a society that divides us in the American ways of race and class and comes out unscathed? Do we imagine there can be no intrapsychic cost? How, as a white person, to find an embodied language for this pathological situation? How might psychoanalysis, as a tool for making the invisible visible, situate itself in relation to this problem?

For the problem is such that we can’t think our way out of it, can’t talk or write our way out of it, certainly not in any simple or straightforward way. We live it and breathe it, and it lives and breathes inside our bodies, inside our conscious and unconscious American minds. ▪

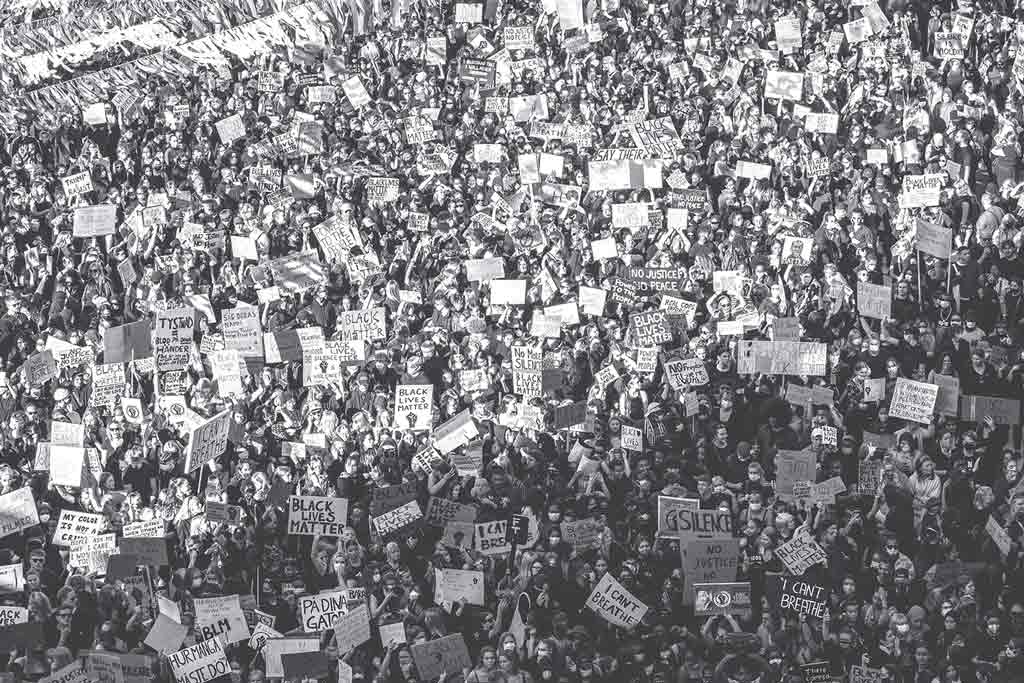

Photo by Teemu Paananen | #BlackLivesMatter protest in Stockholm, Sweden.

-

Gabriel Heller is a candidate in the adult program in psychoanalysis at IPTAR and teaches writing at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. His stories and essays have appeared in The Best American Nonrequired Reading, Crazyhorse, The Sun, War Literature & the Arts, Witness, and other literary publications.

- Email: gbrlheller@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |