BLACK AND BLUE

by Lee Jenkins

“What did I do to be so black and blue?”

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

We talk about the blues as sadness and transcendence of sadness. As an American Black, my experience tells me that it certainly seems to be both of these things simultaneously—contradictory things existing together, something we psychoanalysts know about. To me it’s about acceptance of the inexorable challenge and difficulty of being alive. We all know about this in the experience of the elusive happiness or contentment we pursue in life. It often does not arrive, and when it does, it’s often in a form we hadn’t expected. There’s the possibility of the constant presence of frustration and lack of fulfillment in our accomplishments and in our relationships, though we keep trying. There’s a hopelessness in this also because we know that death will come, yet we act like being extinguished is a distant, abstract construct.

In an immediate way, the blues is about life’s inconsistencies: one can say that yesterday was hard, and I didn’t think I’d make it, and thought I’d die, but I woke up still alive this morning, and in this moment I’m grateful. Or my lover and I had a bad argument, said hurtful things, but we made up; it’s the sweetest thing, and I can’t help singing about it, whether with my voice, piano, saxophone, guitar, or harmonica—tomorrow I may not be here or may be loveless, hopeless, and bereft once again. The blues is a response to the most basic pleasures and agonies, the simplest of things yet the most profound.

We know that love is wonderful but may not last or is complicated by ambivalence. The same could be said of truth, faith, loyalty, endurance, fortitude. Exhaustion and betrayal may arrive. Yet there is something indomitable about the human spirit, as we call it, that faces adversity and strives to endure, as William Faulkner said, even overcome—at the same time, in the end, we know we will finally be forced to succumb.

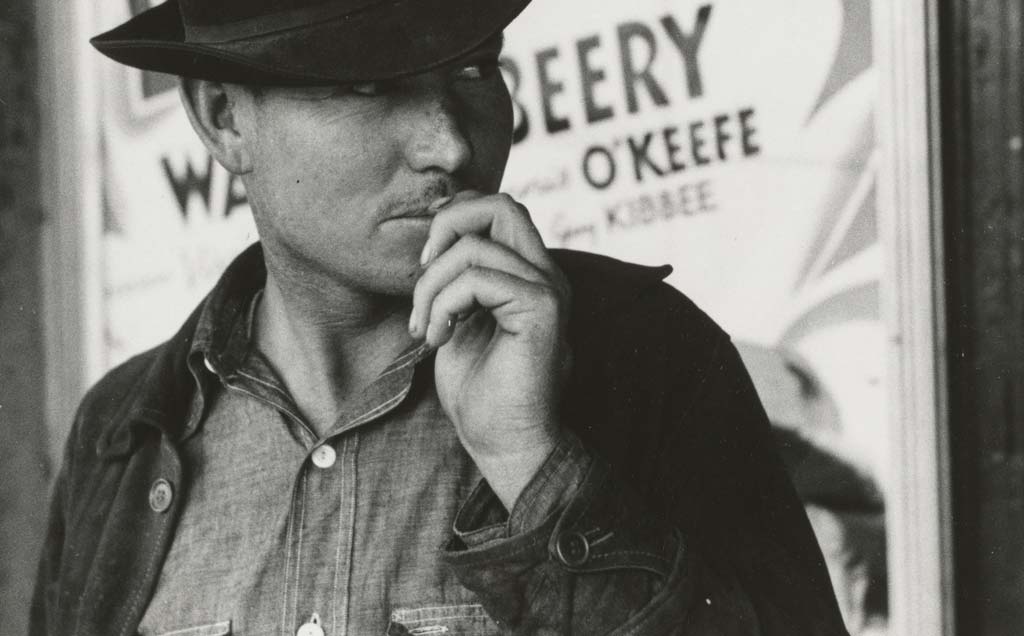

This human effort has been given a special, signifying image and meaning in the lives of Black Americans, who’ve endured a history of the most demeaning and destructive betrayal of their humanity, from enslavement to the present-day undermining of their existence. They have had to live with the legacy of enslavement and ongoing racist subjugation, exposure to the possibilities of rejection, dismissal, belittlement, and dehumanization—such an immense capacity to absorb pain and suffering and keep on going, surviving. It takes resilience to do this, some kind of existential strength. It takes all the psychic energy a person might have. Blacks continue to try to hold on to self-respect and to be able to raise children, live with a mate, and have hope for the future, still be able to love and get along with others and even contribute to a society that doesn’t want them. This is an immense achievement that is not much acknowledged. Yet they have endured, finding some way to resist self-hatred and oppose the contempt they’ve received, with the possibility of caring concern for themselves and their kind.

This has, in many ways, captured our imaginations. I think it also serves as a means for those of us who are white to observe a human triumph and wonder if it is an image of the human spirit at work or just a special representation of blacks confronting their degradation and not something in which the rest of us can see ourselves. Yet the spirit of the blues is alive, is something Americans have already adopted, as in having the blues or being blue. Can we see that the blues has simply reminded us of the difficulty we too can experience being alive?

Perhaps to suffer is not to experience something different in kind but only in degree, if it is true that we share a common human heritage, experiencing a common human limitation. The blues is what human beings express when confronted with adversity with little possibility of escape. It engenders acceptance of one’s plight (think of concentration camps) at the same time that it grinds opposition into place. Is not this the contradictory state of being alive? The blues gives a picture of what this state looks like, as experienced by American Blacks, as a statement of what can happen to humans.

-

Lee Jenkins is a professor emeritus of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, a poet, novelist, and psychoanalyst practicing on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. He has a PhD in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. He received his psychoanalytic training from the National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis (NPAP). He has served as an instructor, supervisor, and training analyst at Blanton-Peale Institute, the Harlem Family Psychoanalytic Institute, and NPAP. He is the author of Faulkner and Black-White Relations: A Psychoanalytic Approach (Columbia University Press, 1981); a first book of poems, Persistence of Memory (Aegina Press, 1996); Right of Passage (Sphinx Books, 2018), a novel; and a second book of poems, Consolation (IPBooks, 2021), all of which can be purchased on amazon.com.

-

Email: LeeJenkins255@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |