Bringing Psychoanalysis to China

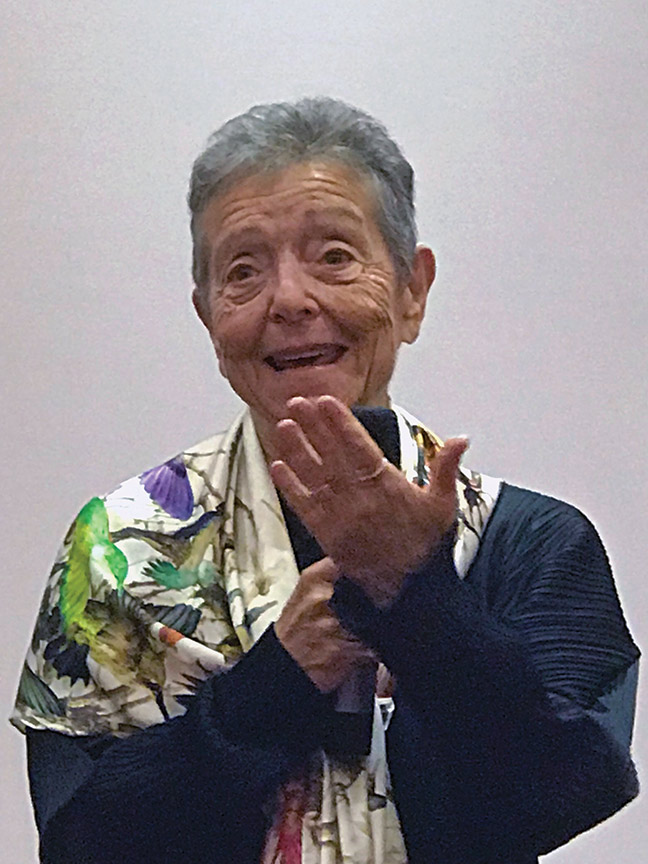

An Interview with Arlene Richards

by Fang Duan

Fang Duan: As someone from China who is now learning psychoanalysis in the US, I am very curious about your “reverse” journey. What brought you to China?

Arlene Richards: I always wanted to visit China. I am Jewish. Several of my good friends here in the US spent years of their childhood in Shanghai, China. During WWII some Jewish people fleeing the Holocaust ended up in Shanghai. They were welcomed and treated very well. The Chinese people shared food with Jewish refugees when they barely had enough for themselves. I am very grateful and I want to do something for the Chinese people as a way of giveback.

FD: The relationship, remote or not, started early. You have personal reasons to bring psychoanalysis to China.

AR: Yes, I do. I first visited China shortly after Nixon’s visit in the late 1970s with a group organized by the American Psychoanalytic Association. To our surprise, when we visited the Shanghai No. 1 Mental Health Hospital, we saw quite an amazing system of care: they had “heart-to-heart” talk (individual therapy), family therapy, and in community therapy they even invited neighbors. They tried to understand every aspect of the patient’s mental and emotional disturbance. And there were also many activities, including music, dance, and occupational therapy. Unfortunately, these services were available only to the very “valuable” few.

FD: Very sophisticated.

AR: Yes it is. Then in 2006, I received a phone call from Dr. Tong in Wuhan. She had read my work on female psychology and development. They had a big problem they thought I could help them with. Young women, only daughters of a class that had power in China, were dying by suicides. These women were expected to continue the family line. Also, because their parents had achieved so much, they were expected to excel and make their parents proud. Not everyone is equipped to accomplish that much. Besides, many of these only daughters did not grow up with their parents who had been busy working. Now as adults they felt they could not measure up and were terribly depressed. They were hospitalized, and some even took their own lives in the hospital. It was such a disaster for themselves and their families.

FD: It looks like your idea of primary female bisexuality becomes obligatory in this context. Ideally, girls develop in such a way as to realize their bisexual potential or different aspects of their personality without too much gender restriction. Now these young women felt they had to do both and be everything. An impossible situation.

AR: That is exactly what happened. An unsustainable situation. Then I flew to Wuhan with my husband. For two weeks we gave lectures, did supervision and interviews. It was very successful. By the end of the trip, we were given a lovely banquet. I was seated next to the governor of the Hubei province, who had his own reasons to be grateful. We chatted. The governor told me that his biggest regret in life was that he missed the childhood of his only daughter. He hoped one day he could be a grandpa and watch his grandchild grow. He would not miss any milestones. He talked with such eloquence and passion. I was moved and said, “This child is going to be lucky.” I shared that I was raised by a grandpa because my mother was busy at work when I was little. It was an arrangement that worked for all. The governor was very interested. I then recommended a book I was given to read as a child when I told my mother other kids at school were teasing me: “You don’t have a mother and you only have a grandpa.” In this book the little girl Heidi was sick. She was sent to live with a grandpa who did not put any pressure on her. Grandpa simply looked after her and enjoyed her. Heidi got well. The governor responded, “Is this what psychoanalysts do?” I said, “Yes it is. This is what we do.” The governor said, “This is a good thing. I will build you a new hospital.”

Within six months a new five-story building for Wuhan Tongji (meaning “Sailing in the Same Boat to Cross a River” in Chinese) Mental Health Hospital was finished. This building houses our new Sino-American psychoanalytic training program.

Since then we have been travelling to China to train mental health professionals twice a year in the spring and fall, each time for two weeks. In between we continue the work on Zoom, and last year, due to the COVID, the program was disrupted, but we tried to pick it up entirely online. We have graduated two three-year classes, each of two hundred fifty students. Now for the third class we have five hundred students. The students selected for training are usually heads of the local hospitals or psychiatric departments and they go back and teach their staff what they learn at the program.

FD: I heard this Sino-American program is very influential in the Chinese mental health community, along with a Norwegian program and a German program, all following a “train the trainers” or “teach the teachers” model. What is significant to me is that this program was established through a personal connection you made with this governor. I think perhaps the “personal” element is what makes psychoanalysis especially appealing to a society that does not traditionally emphasize the individual and the personal.

AR: Somehow it happened. In China, things happened from top down. In the beginning the issue was with the only daughters of people on top. Unfortunately mental illness is quite an equalizer.

FD: I think psychoanalysis helps people understand we are more alike than different on the inside, despite all those external categories of distinction. Psychoanalysis has become quite popular in the Chinese mental health community and academia. Based on your experience, why do you think people in China are embracing psychoanalysis now?

AR: I think it has to do with trauma, trauma of violence and trauma due to radical social changes from China’s recent and long history. Just from the last few decades there have been wars, political movements, great famine, cultural revolution, and then came reformation and opening up. The society is changing so fast, as if the ground on which people stand is constantly shifting. Trauma happened on such a large scale. Almost every family was affected. It seems that so much destruction or disruption is built into the fabric of the society. Several decades ago a six-year-old went to school and he came back only to find his beloved grandma hanged herself in the kitchen. Is it surprising now this man suddenly lost his high functioning and developed a debilitating fear? As we just mentioned, “becoming a woman” could be such a complicated, heavy issue for an entire generation of only daughters. But it is not something they talk about openly.

FD: Recent China has seen this spectacular burst of energy and, at the same time, so much psychological damage. There is so much need for psychological assistance. What is the most challenging part in your psychoanalytic work in China? Do you experience any “culture shock”?

AR: The major issue is shame. Compared with patients I see here in the USA who are more troubled by guilt or conflict, my Chinese patients are more troubled by shame. They worry about how what happened may look to others. They feel ashamed that they need help, especially psychological help, as if they should just toughen up and get over their pain on their own. It is often very hard for them to talk about what they went through. Left unspoken, these unspeakable, unmentionable traumas from the past remain so alive, motivating. The impact could be disastrous.

FD: The experience of shame is also prominent in my psychoanalytic work. I think the wound of shame is more pervasive, global, and it cuts much deeper, damaging people’s core sense of humanity. I don’t think injury at this level could be easily mended by short-term or cognitive treatment. It takes psychoanalysis as a change agent at the ontological level to bring about lasting transformation. How do you work with shame? What sort of technique do you think is most helpful in your work with the Chinese colleagues and patients?

AR: I would not say it is a matter of technique. I think it is more a delicate touch, a respectful, learning attitude. To make them feel valuable. I try to make them feel they have valuable things to say, their thinking and feelings are the most important things in the room. I ask them to help me understand what it is that I am not seeing. If I have an interpretation, I check with them: “Did what I said match up with how you feel?” When I get a negative reaction, I say: “Here, I was wrong again.”

FD: Talking helps. And you have a very gentle, affirmative approach, relating at a deeply human level. Thank you very much.

AR: Thank you.

- Fang Duan, PhD, LMSW, is a Chinese Canadian living in the United States, a psychoanalyst in training at the Institute of Psychoanalytic Training and Research, New York. Working with a diverse population from various social-cultural backgrounds, she is interested in exploring, clinically and theoretically, the implications of psychoanalytic thinking for individual and societal development.

-

Email: fangduan14@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |