FROM BEIRUT TO SAN FRANCISCO

by Karim Dajani

“AWASSNI, AWASSNI.” The man screamed these words before letting out a guttural cry. Awassni is Arabic for “he shot me.” It had been some years since the war began, and most of us had learned to distinguish sound more keenly. We can tell, from the sound alone, how far the bullets are being fired from, the types of exploding shells and likely shrapnel radius, the type of warplane buzzing above our heads. Depending on the distance of the warplane, we learned to anticipate the time it took for a missile to reach the ground in a fiery explosion. Death, destruction, mayhem, and the screams of people dying and grieving would inevitably follow. This one was close. I looked out the window to see a man dying on the ground. I was too young and scared to walk into the streets to help. Even if I did, more people would be shot and lie dying on the pavement that day and the next.

Lebanon is burning in civil war. But the people have to live, so they walk the streets despite the fact that most roofs have active sniper dens, shelling is indiscriminate and unpredictable, and checkpoints where people who are identified as belonging to a different sect or large group are beheaded on the spot punctuate the streets of every neighborhood, and Israeli warplanes fly over on a daily basis, occasionally firing missiles on us.

The streets are dangerous, and the people are on the verge of collapse. How does a child live in a collapsing world? The Mediterranean Sea is a stone’s throw from our house, so I spent much of my time in it dreaming of a better world. Earlier that day, I had gone to the sea to play a game that I often played, particularly when I was sad. I would walk out onto a rocky area on the sea’s edge. The rocks were jagged, their crevices full of thorny sea urchins. In various parts of this rocky terrain, holes are formed, presumably from years of erosion. The holes are narrow openings that cleave the rocks. Crashing waves fill the holes before the water retreats, creating a “sharook,” which is a type of suction that pulls you into the sea’s depth. Getting in and out of the sharook without getting seriously injured or killed was the aim (maybe) and the thrill. I waited for a coming wave and dove into the sharook’s rising water only to be sucked deeper into the sea. On the way down, my twelve-year-old body was thrashed on the rocks. I felt helpless and out of breath. I wondered if I was going to die. I resisted and, with all my might, pushed my way out of the water and onto land again. My legs were scraped and the bottoms of my feet riddled with sea urchin needles. I hobbled home. My mother was genuinely frightened, but she cared for me as she screamed and cried.

That night, I had a dream that I was sucked into a sharook and my body got stuck in the rocks. As my breath drained and I felt myself slipping, a voice came into my ear. It commanded me to breathe. How do you breathe underwater? Breathe, the voice replied. I did and my lungs filled with air. I felt buoyed with hope and a sense of mystery that has remained with me till this day. Deep inside, I knew that I would find my breath even when my body is shredded on a rock and submerged under the sea. I will breathe even when a violent death is likely. Poseidon, with all his might, told me so.

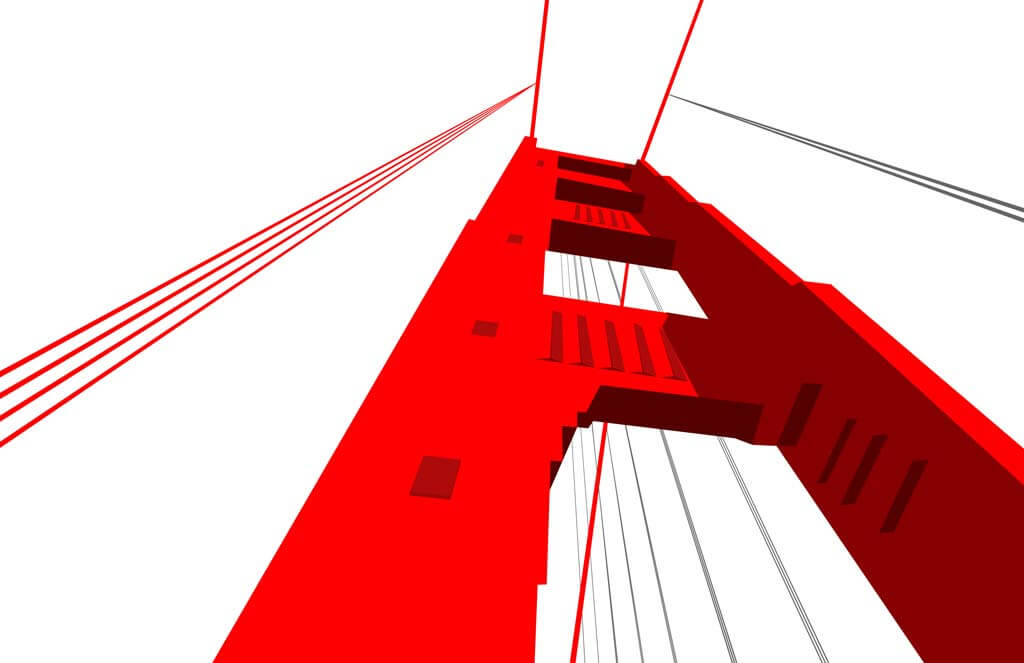

The unlikely journey from Beirut to San Francisco was long and painful. It paved the way for an even more unlikely journey of a traumatized Palestinian kid becoming a psychoanalyst at the San Francisco Center for Psychoanalysis. To do so, I had to learn to breathe in impossible places.

When I matriculated at SFCP in 2005, the culture of the place and of the field was committed to the idea of the unconscious being an individual biological phenomenon. Culture and the social were treated as external to the unconscious and, therefore, not part of psychoanalysis proper. The way that played out in classes, supervision, and our own training analysis was that pain and the meaning of emotion were always located in the individual and between the individual and the family. Genuine suffering that came from outside my body and my family walls was largely overlooked or shoehorned into conceptions of the mind that did not include the constitutive links of culture and history. I was willing to take this stance on good faith and out of a need to fit in. I applied it to myself and to my patients. But it did not work as well as promised. My experience and my observations surely pointed to culture, context, history, and the social writ large as deep links in the very structure and function of my unconscious. Trying to fit into a worldview that denied the powerful and ongoing impact of the sociocultural was like trying to survive being thrashed on rocks and pulled into the sea.

I responded to this problem by studying. I pored over the literature. I chronicle the evolution of my thinking about this problem in academic publications elsewhere. Here, I will communicate a few observations and link them to a story we are all familiar with.

Psychoanalysis has struggled with how to understand the link between the individual and the sociocultural surround. The debate about the role culture and the social play in structuring the unconscious goes back to the very inception of the field. Analytic scholars across continents, cultural systems, and languages were arguing that culture and the social are not superficial or cosmetic aspects of the unconscious but constitutive, meaning they structure the way we unconsciously think, perceive, and attribute meaning to ourselves and the world. Their voices have been consistently marginalized from our history, theories, and curricula.

The marginalization of analytic scholars who argue for the centrality of the group and culture in the organization of individuals is a repetition of a trauma that originates in the social. European and American societies are struggling with their history and cultures as they pertain to issues of race, oppression, and power. The systemic marginalization and oppression of minority groups (BIPoC, women, LGBT+Q, immigrants, etc.) hurts our national collective and retards our social evolution. Similarly, the systemic marginalization and oppression of analytic voices who challenge the dominant group’s assumptions and praxis hurts the field, retards our evolution, and diminishes our relevance. The way we are is operationalized in the cultures we use, and the cultures we use reflect the way we are.

Culture is like the air we breathe; it animates our bodies. Culture or the collective, paradoxically, gives us the necessary tools to realize our individuality. The sociocultural is breathed into us from the very beginning. It constitutes the deepest layer of our unconscious while lying in plain sight. If the air we breathe is full of toxins—oppression and marginalization—then the self we make is full of those toxins as well. We have been slow to analyze this dimension of our being as the societies we live in have also been slow to recognize the way systemic racism is baked into the air we breathe.

A biblical story comes to mind. In the beginning, God fashioned clay into the form of a human body and blew breath into it. Divine breath animated the clay and turned it into a human subject, Adam in this case. Adam, our first human, is made from clay (body) and breath (material that comes from outside of it). This is a shared idea. It finds representation in the social unconscious of individuals and groups who have inculcated it. This applies to me as well. Here is my modified reproduction of it.

Initially, the ideas of air and breath can be assumed to be universal phenomena or objective observations of reality. All people need air to breathe, and breathing is essential to life. If you cannot breathe, you will not live. This is a universal truth.

Digging a bit deeper, we can see that air and breath are actually variable and contingent phenomena. The air we breathe is not the same; it varies from environment to environment and is contingent on human activities and constraints. Breathing the air in New Dehli is not the same as breathing air in London, Bangkok, Beirut, or San Francisco. I am not talking about levels of pollution here. I am talking about culture being the air we breathe.

When I first immigrated to the United States at the age of fifteen, I had to learn to speak English and to find my way in a culture that felt painfully foreign. This painful sense of foreignness, weirdness, and deeply unfamiliar ways of being filled the air and came into me with every breath I took. Thirteen years after immigrating to the United States, I took my first trip back to Beirut to see my ailing father. When I stepped out of the plane, the air was thick and hot. It carried with it distinct smells, sounds, and sensations. It enveloped me. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, came the Muslim call for prayer. It was blasting from a nearby mosque. The rhythmic sound, the words, the cadence filled the air and came into me with every breath I took. It felt painfully familiar. The social is the air we breathe.

Dreaming is mysterious. In a dream, I was shown how to breathe while underwater. I did not know then that it was a message from the future. I barely survived the war and I barely survived coming to America. Much to my surprise, in the United States, I was perceived as a brown inferior other. I was beaten by groups of white teenagers for being “an Arab with a funny accent.” Underwater, I found solace and belonging in the company of African Americans in the ghettos of Washington, DC. We played the blues and felt each other’s history.

Entering an analytic institute that is run by a group of affluent, white training and supervising analysts who conveniently deny the impact of culture and the social on individuals, groups, and institutions is like being underwater. I am lucky. I found a small group of kindred souls that give me solace, a way to belong, and the courage to think for myself. We are in the process of cleaning up our system, theories, curricula, and praxis—infusing breath into a stultifying system.

Making the improbable probable is what we all need, and it is quintessentially psychoanalytic. Can we clean up manmade pollutants in the air we breathe, so we do not shock this planet to death? Can we address the scour of systemic racism in our cultures, societies, and praxis? Can psychoanalysis become a useful and accessible tool for all those who want and need it? Can we imagine living in peace with each other and in harmony with nature? It will take finding our breath while underwater and thrashed on razor-like rocks. It is improbable but possible. Let us dream of a better world together. ■

-

Karim G. Dajani, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst in private practice with a specialization in treating bicultural individuals. His research and writing include publications on psychological resilience and culture. He focuses on the role culture plays in determining an individual’s role within a collective and on the experience of cultural dislocation.

-

Email: karimdajanisf@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |