THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF BORDERS

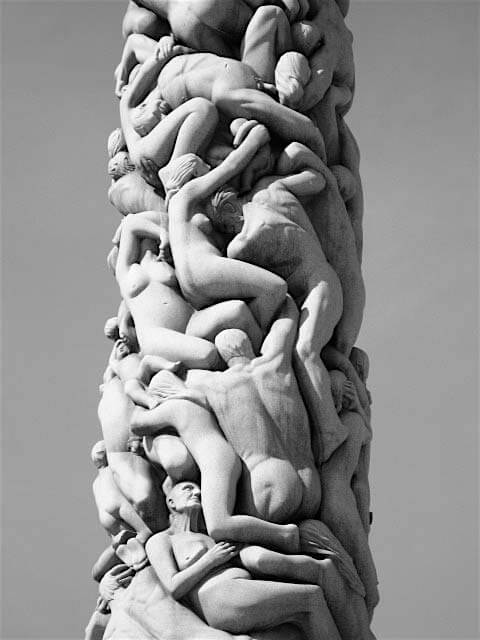

by Simon Western. Photo by Simon Western.*

We live in a world of borders. Territorial, political, juridical, and economic borders of all kinds quite literally define every aspect of life in the twenty-first century. (Nail, 2016)

Crossing borders in the recent past was probably less confusing and demanding than it is now. Institutions, social norms, and rituals made borders more rigid, and prior to the digital revolution and hyperglobalization, borders were more stable. They were never fixed but were less fluid than in today’s disruptive world. We live in confusing times, where more borders are appearing all of the time and where many borders are disappearing or becoming more porous.

Individual and social anxieties are rising in response to borders being made and unmade at a phenomenal pace in the past few years. The phrase “crossing borders” unleashes a chain of associations and meanings in society today. When we think of crossing borders, national boundaries, immigrants, and passport control may immediately come to mind. Walls, fences, security barriers, and checkpoints are all associated with borders, yet many other borders exist that we have to cross multiple times each day. As borders become unstable and more fluid, individuals can become anxious and threatened. The unmaking of borders and the dismantling and loosening of border regimes remove obstacles and create radical new possibilities and opportunities for some, while threatening others. The making of new borders and the tightening of border regimes create hardship and marginalization for some and a feeling of security for others.

Borders and movement

A border controls flows of movement. (Nail, 2016) It can act as a barrier, returning a flow of movement back on itself, or as a filter that allows some things to pass and others not. A border may also be a boundary or an edge; it can be man-made or naturally occur in the environment, such as the Himalayan mountains creating the border between India and China. Borders are not only material manifestations, but are also found all over the virtual world, and borders also inhabit the space between physical and virtual spaces, controlling the flow of accessibility to the virtual world, via passwords for example. Borders also occur within us and between us. Emotions, affects, and thoughts flow, crossing internal borders within each of us, and also flow between us as relational phenomenon.

Border regimes within us

In my work as a coach, therapist, and consultant, I am constantly crossing the borderlands between the conscious and unconscious worlds. When exploring a client’s unconscious, psychoanalysis teaches us that something important is at stake when the clients’ defense mechanisms kick in, and they offer resistance. The psychoanalytic concepts defenses and resistance echo military language; for example when a force encounters an enemy’s border, they too meet defenses and resistance. This mirroring of language reveals how closely our internal borders relate to external borders. Our internal worlds impact and shape the external world.

“I saw that beautiful barbed wire going up.”

President Trump, November 3, 2018

US President Donald Trump and his followers export their internal fearful mind-sets, that see “the other” as a dangerous invader, through their rally cries and Trump’s promise to “build the wall.” Interestingly, the other chant at Trump’s election rallies — “lock her up” (referencing Hillary Clinton) — is also about walls and borders, in this case the walls of a prison. The demand to build walls and lock people up signifies the internal desire for punitive security borders to be inflicted on the “bad other,” so the self can feel safe and secure at both physical- and emotional-identity levels. Psychoanalysis teaches us that when we create a “bad other” in our minds, it usually represents a split-off part of ourselves, an unwanted aspect of ourselves that we cannot consciously tolerate, so we evacuate the bad or disliked part of ourselves and project it onto others.

We create internal security borders, behind which our repressed anxieties and dormant fears lie. As with most borders, however, they are never 100 percent secure, and leaks occur. In this case, our unconscious life seeps into our consciousness, often in displaced ways. Making new borders and reenforcing existing border regimes are simplified solutions politicians use to mobilize popular support, claiming it will protect the “good/us” from the “bad/them.” The Brexit cry of “take back control” is another example. Taking back control means to many the remaking of a lost border to prevent the free flow of people. The conscious and unconscious borders within us, and the relational borders between us, constantly regulate our libidinal flows. Our emotions and affects, our drive and psychic energy are regulated by border regimes within us, between us, and external to us.

Internal mind-sets produce external realities. Internal anxieties and fears produce nationalist politicians, external walls, scapegoats, and repressive laws. This also happens in reverse. Our internal worlds are shaped by external realities; when physical borders impose themselves on us each day — for example the Berlin Wall during communism or the Israeli security wall or apartheid wall (depending on which side you live on) or the gated communities of Johannesburg where high walls, razor wire and security guards dominate the landscape — an unconscious internalization process takes place. We internalize the walls and border regimes, and they create normative mind-sets that limit and shape how we live. Internalizing restrictive border walls creates defensive and fearful mind-sets.

Luxurious Prisons

When the powerful build border walls to defend themselves against an undesirable other, the wall impacts both sides. The gated community in a city acts as a defense against the poor, but it also encloses the rich in a (luxurious) prison, and both sides internalize the impact of this. A border controls both the flow in and out. While walking in Johannesburg’s wealthy districts, I experienced the dystopian future that is becoming normal in other cities: high walls, razor wire, security gates, security guards, and nobody walking or cycling, just people locked in their houses and cars. What mind-sets and cultures are internalized when we live with border regimes that are so pervasive, defensive, and also aesthetically destructive?

Digital Border Regimes

This internalization of border regimes also occurs in our encounters within the virtual and financial world. In recent years, we find ourselves constantly crossing virtual borders, signing in and using security passwords. Each time we shop, buy something online, visit a website, we cross a border, each with its own way to control and restrict the flow of movement. We internalize the experience of being constantly monitored by these digital border regimes, checking we are human and not robots, and expelling us from places beyond our reach. These new online border regimes are a dominant feature of our daily existence, and we can internalize a sense of the world being a place of borders. The constant boundary crossing, the warnings of dangerous viruses and cyber attacks; the fears of being shut out or discriminated against; and the frustration at not able to cross the border create new anxieties, frustrations, and even rage in the digital age. Yet the paradox is that IT, the internet, social media, and mobile communications can also erase borders, making connections possible that were once impossible. Techno-utopians still dream of new radical democracies and open societies modeled on open-source technology and new possibilities of the commons. Knowledge and information that once required difficult border crossings and were only available to elites are now freely accessible at the click of a mouse. We live in times where huge, new potential exists and vast open spaces appear, while at the same time more borders exist than we could have possibly imagined in the past.

Shifting Borders

Despite the celebration of globalization and the increasing necessity of global mobility, there are more types of borders today than ever before in history. In the last twenty years, but particularly since 9/11, hundreds of new borders have emerged around the world: miles of new razor-wire fences, tons of new concrete security walls, numerous offshore detention centers, biometric passport databases, and security checkpoints of all kinds in schools, airports, and long various roadways across the world.

(Nail, 2016:1)

Borders are both being made, and unmade, at an unprecedented rate. This relationship between the making and unmaking of borders is symbiotic, each force impacting the other. As borders are unmade, new anxieties are unleashed that create a drive to make more borders. As borders are made, activists strive to open up new spaces and loosen border regimes.

Here are three examples revealing how contemporary borders are being made and unmade.

1. Trade Borders

Globalization, neoliberal free trade, mass air travel, and the EU’s four freedoms of movement (finance, people, goods, and services) are examples of a radical unmaking of borders in recent times. Neoliberal capitalism offered a vision, at least on the surface, of open trade and free markets (although many would claim that elites created hidden borders under this rhetoric of freedom excluding many from accessing a share of the wealth that was created). There is currently a counterrevolution against these globalizing forces to create new borders that protect national trade and the movement of labor (e.g., Brexit and economic nationalism elsewhere).

2. The Digital Age

The digital age unmakes borders in ways we couldn’t imagine in the last decade, unleashing new possibilities, huge opportunities, and also unforeseen consequences. As discussed earlier, there is also a rapid proliferation of borders in the virtual world. Microsoft is a good example of a company that managed to exploit the virtual world of border-making to create vast profits. Through the licensing of their software (Word, Excel, etc.) and creating restrictive borders that prevented open use, they created their vast business empire.

3. Identity Borders

Another unmaking of borders comes about through a radical changing of legal and emotional identity borders. Same-sex marriage and transgender rights are examples of the unmaking of border regimes both legal and cultural, which defined identity norms for past decades. The unmaking of these borders is hugely liberating for many and threatens the identity of others. The speed of this change is phenomenal. For example, in Ireland, a conservative Catholic country, recently voted in a gay Taoiseach (prime minister) and held a referendum that allowed same-sex marriage. These changing border regimes are part of what some call the “culture wars” taking place in the United States and other places in the West, some fighting for more borders, some for less. Interestingly, those who fight for fewer borders for marginalized people to gain rights (such as transgender rights) are seen by others to be imposing new border regimes that restrict free speech and thinking. Borders are not straightforward; they are complex and enmeshed in power relations.

For better or worse, our individual and collective identities are at stake when borders change. Accommodating fast-changing border regimes requires sensitivity and maturity. It also requires us to reflect on how these border regimes impact on our intimate as well as political and social lives. ■

-

Simon Western, PhD, is president of ISPSO, adjunct professor at University College Dublin, and CEO of Analytic-Network Coaching. His Advanced Coach Training program has a global footprint, using contemporary

psychoanalytic methods to develop leaders and help them adapt to the digital age. He is the author of Leadership: A Critical Text (3rd ed., Sage, 2019), Global Leadership Perspectives (Sage, 2018), and Coaching and Mentoring: A Critical Text (Sage, 2017). -

(1) Nail T. (2016) Theory of the Border. Oxford University Press

-

(2) Western S. (2015) Political Correctness and Political Incorrectness, A Psychoanalytic Study of New Authoritarians.

-

Email: simon@analyticnetwork.com

- Photograph by Simon Western. The Monolith, Vigeland installation in Frogner Park by sculptor Gustav Vigeland, Oslo. Norway.

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |