Pages in the Park

The sodden pages were splayed out on the bench below a Riverside Park Conservancy banner. I glanced up and down the promenade, hoping to alert the book owner. It was 7:15 a.m. on Sunday, July 16, and it was raining. The park was empty. Earlier, I had skimmed the Guardian and the Times, read Bill McKibben’s latest Crucial Years piece, and checked the air quality, the expected heat, and the latest news on the devastating fires, heat waves, and floods the world over. My usual morning routine.

I had to get out ahead of the day’s pollution, heat, and expected thunderstorms and away from my despair. I needed trees, birds, flowering shrubs, and I knew where to find them: Riverside Park, the wonderful miles-long park that runs along the upper western edge of Manhattan next to the Hudson River—a short walk from my apartment.

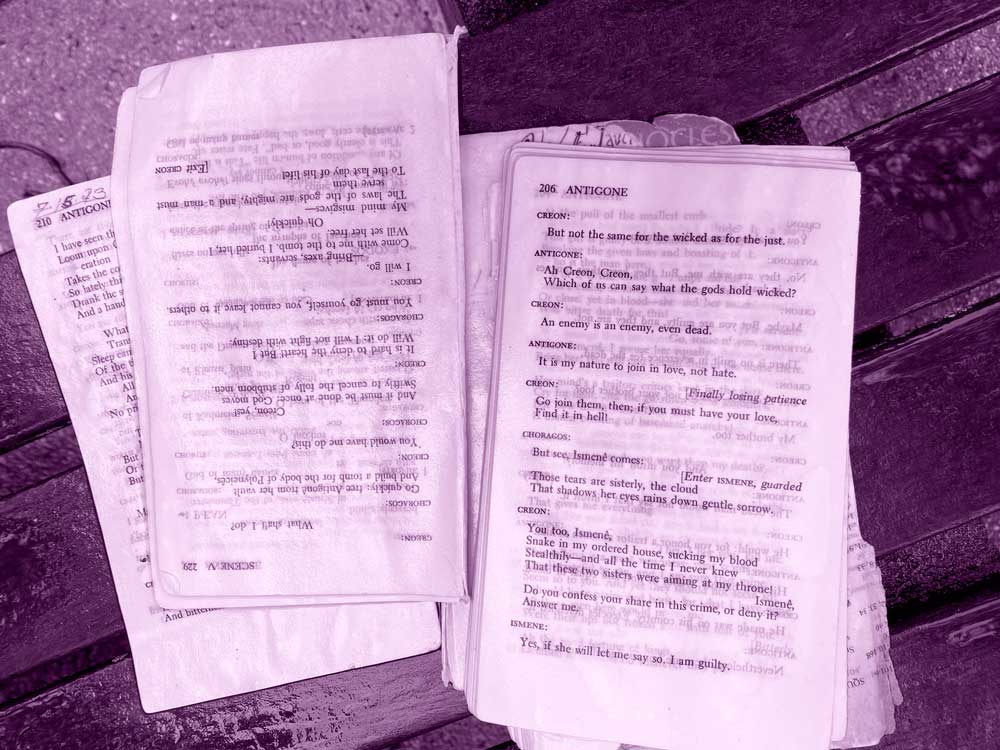

I had been photographing rain within the hearts and throats of flowers when I saw the pages on the wet bench that overlooked the West Side Highway and beyond to the racing waters of the Hudson. Looking more closely, I recognized the pages as the play Antigone. The two pages on top, 206 and 229, upside down from each other, were not consecutive. Had the reader taken the chunk of the book containing missing pages 207–228 because they had particular significance? Or was the intent to highlight these two remaining pages in the hope that a passerby would pause to read them. To alert them—me? —to the 2,500-year-old moral discourse on these pages? Carefully lifting the remaining wet sections, I found a torn cover and identified the book as a copy of the 1959 Harvest Books edition of Sophocles: The Oedipus Cycle, translated by Dudley Fitts and Robert Fitzgerald. How strange! I had only recently given my worn copy of the same volume to a local thrift shop as part of my effort to downsize my enormous library, which includes multiple translations of all the existing plays of Sophocles.

At home later, I turned to the University of Chicago Press’s The Complete Greek Tragedies: Sophocles I (Second Edition, 1991) containing David Grene’s translation of Antigone. Lines 592 to 1173 of Grene’s version corresponded with the missing pages. They follow the impassioned dialogue between Antigone and Creon, upon confirmation that she, by partially burying the body of her dead brother Polyneices, has disobeyed Creon’s decree that the body must be left untended, as carrion outside the city walls. This dialogue—part of which is on the waterlogged page 206 left on the bench—is about the conflict between the law of the state or dictator and a conflicting moral imperative of the citizen. In this case, that is Antigone’s sense of a higher order of moral obligation to provide funeral rites for her brother, even on the penalty of death. The other page exposed on the bench, 229, picks up where Creon, having buried Antigone alive in a subterranean cave, is suddenly anguished by the subsequent prophecy of great loss and misery befalling him and his family. He changes his mind and rushes to undo what he has done. His last words—visible on page 229 on the bench—are “The laws of the gods are mighty, and a man must serve them to the last day of his life!” Grene’s rendition of the same speech: “It may be best, in the end of life, to have kept the old accepted laws.”

Pages 207 to 228 appeared to be missing from the bench altogether, except for page 210, which was partially visible. Our unknown bench sitter had written the date, 7-15-23, across the top, and when I lifted the overlapping page, I saw that they had also written “July 15, 2023, Saturday” in blue inked script with a mature flourish, as though to emphasize our time and place: This is now! The twenty-first century! Standing in the early-morning rain, looking at those pages, wondering about intentionality, about meaning, I had an uncanny feeling of presence. As though the unknown reader had been there only moments before. As though these pages were from the same physical copy I had recently donated—that this book went from my hands to the hands of the unknown bench sitter, who only hours earlier had written the date on page 210 and left the dismembered book on this bench for others to be stirred and provoked by the discourse on responsibility, moral choice, self-examination, and action inherent in Sophocles’s remarkable words. And why write the date on this particular page above the tragic words “I have seen this gathering sorrow…”?

In the Grene translation of the lines of this chorus speech referring to Fate, the passages chillingly evoke concerns of our times: false news, hate speech, distortions of truth, and suppression of science. Grene’s lines 599 to 603 correspond to Fitt’s passage below that handwritten date:

Here was the light of hope stretched

over the last roots of Oedipus’ house,

and the bloody dust due to the gods below

has mowed it down—that and the folly of speech

and ruin’s enchantment of the mind.

Later, in lines 616 to 622, Grene renders the ominous words penned long ago by Sophocles as:

For Hope, widely wandering, comes to many of mankind

as a blessing,

but to many as the deceiver,

using light-minded lusts;

she comes to him that knows nothing

till he burns his foot in the glowing fire.

[…]that evil seems good to one whose mind

the gods lead to ruin,

At the time Grene made this 1991 translation, much was already known about our impending planetary crisis. In 1988, Dr. James E. Hansen warned the US government that rising greenhouse gases from extraction and burning of fossil fuels would result in global warming and untold harm to our biosphere. Even before then, Exxon executives began spending millions to suppress climate science, falsify the findings of their own scientists, and distribute false “science.” The massive Exxon PR budget was used to propagate false hope and false blame including inventing the concept of your personal carbon footprint, thereby laying responsibility at the consumer’s feet. Whether it was our unknown park bench reader’s intention or not, the words of Sophocles in Antigone seem ready to be applied to these, our troubled times.

We are left with so few of Sophocles’ many plays. There is evidence that there were other Theban plays in his opus, and the three we have are not meant to be a trilogy. Nevertheless, it is intriguing that Antigone, though chronologically the last story of the Theban myth, was written and performed when Sophocles was in his fifties, while he was a state treasurer and a general involved in both military and diplomatic action. This was a time of his life when he was intimately concerned with matters of state power and democracy. His Oedipus Rex was written a few years later, and his Oedipus at Colonus was written close to his death at age ninety, at the time Athens faced its devastating ultimate defeat in the Peloponnesian Wars.

That Sunday morning, I left the pages as I found them, planning to return later in the day. In order to mark the location, I looked up at the Riverside Park Conservancy banner above. It bore an image of the Jeanne d’Arc statue. Surely this placement of the pages from Antigone underneath the Jeanne d’Arc banner was not a coincidence. Jeanne d’Arc died at nineteen for defying the state for what she thought was a moral cause. Antigone was about nineteen when she defied Creon. Sinéad O’Connor was twenty-six in 1992, when she tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II after singing Bob Marley’s song “War” on SNL. The list could go on. Greta Thunberg was recently charged with the crime of “disobedience to law and order” and fined. The young environmental protester Manuel Paez Terán was shot to death by the Georgian state police in a forest park in southern Atlanta when, as part of an environmental protest and occupation against the clearing of the suburban forest park to create a “cop city,” he refused to leave his flimsy tent and peacefully defied the police order. The Georgia state legislature has now defined environmental protesters as domestic terrorists.

If nothing else, these ancient words and our modern-day Antigones—all brave young people brutally punished for standing up to the great powers of their day—must bring to our attention the need to grapple with these great timeless and universal moral questions. And alert us to the dangers of our own times, which call us to follow our moral conscience and not to fear the pyre.

Later that day, I returned to the park. The sunshine and the people had come out. Happy dogs were playing and barking joyfully. The velvety purple morning glories were fully open, and the sunflowers were nodding in the breeze.

All traces of the wet book were gone.

- Josephine Wright, MD, is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who has worked with adults, adolescents, and children for more than four decades in New York City. Besides devoting more time now to fiction and nonfiction writing and her Substack blog, migrations and meditations, Jo is also a supporter and activist in environmental groups and issues and an avid student of meditation practices. She currently divides her time between New York City and northwest Washington State, where she is part of a group developing an intentional, co-housing, eco-sustainable community village.

-

Email: jowright48@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |