PRESIDENTIAL STATES OF MIND

by Frank Putnam

THE META-MESSAGE IN TRUMP’S TWEETS

In addition to the political controversies that they ignite, the contents of presidential tweets are subject to diverse statistical analyses as evidenced by postings on the internet. As a form of do- it-yourself proof, empirically minded tweet investigators offer downloadable data sets and computer code. A public archive (http://trumptwitterarchive.com) containing tens of thousands of time-stamped Trump Tweets (TTs) is available. There, an obsessive bot monitoring the presidential Twitter account updates the archive minute by minute.

As a result of linguistic and sensitivity analyses, we know that in terms of emotional content, TTs are most frequently classified as “negative” or as “attacks.” Statistically, Trump’s attacks on people and institutions most often focus on: 1) weakness (“lightweight,” “loser,” “poor,” “pathetic,” “weak”), 2) stupidity (“incompetent,” “moron,” “clueless”), 3) failures (“failing,” “failed,” “disaster”), 4) illegitimacy (“fake,” “false,” “hoax,” “witch hunt,” “unfair,” “discredited”), and 5) corruption (“crooked,” “liar”, “dishonest,” “illegal”). His all-time favorite word is “great” (some studies find that he uses “great” more often than his next several favorite words combined). His favorite insult is “fake.” His favorite pronoun, “I.”

Some investigators suggest that there are two distinct sources of TTs. The first group, a small minority of all TTs, are believed to be authored and posted by staff on behalf of the president. These tweets are noteworthy for their use of complete sentences, appropriate capitalization, minimum exclamation points, and logical coherence. They are frequently sent from an iPad or iPhone.

The second and major source, believed to be directly authored and posted by President Trump, typically come from an Android device. These tweets are characterized by incomplete sentences, recurrent single words or short phrases (e.g., “sad,” “bad,” “witch hunt,” “fake news,” “no collusion”), simplistic language, random capitalization, all-caps words, misspellings, and bursts of exclamation points. Although a few suggest that the poor grammar, spelling errors, word misusages, and chaotic logic are a deliberate artifice intended to identify the president with his base, others point to rapid corrections of the worst mistakes or inadvertently humorous wordings as evidence that the errors are unintentional (e.g., the famously viral “unpresidented” tweet of 12/17/16 was corrected within 90 minutes).

The president tweets at all hours, but statistically he is most active between 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. and again around 8:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. Monday through Friday, he keeps up a steady barrage, peaking about midweek on average. On weekends, the tweet count falls, typically to about a quarter of an average weekday. However, some of his most virulent “tweetstorms” occur around weekends.

“Tweetstorms,” distinct episodes characterized by numerous, lengthy (often multi-part), rambling, emotional tweets composed of chaotic muddles of warnings, boasts, attacks, analyses/analogies, mocking insults, and shout-outs, are frequently observed following media reports that contradict or question the president’s version of a particular reality.

Trump’s tweets and tweetstorms have been subjected to numerous content analyses, usually in relation to events believed to have triggered them. Their longer term trajectory, however, has received less attention. A February 19 New York Times article1 with accompanying graphics2 revealed disturbing trends in the escalating pattern of TTs attacking the Russia investigation and associated individuals.

TTs reflect not only the president’s opinions; they also reflect his state of mind at the time they were composed and posted. I have not found good descriptions of presidential demeanor during a tweetstorm. Indeed, some discussions propose that his tweetstorms occur most frequently while alone and unfettered by staff. Thus, in addition to their content and organization, one must draw on examples of Trump’s demeanor in roughly analogous circumstances to inform inferences about his state of mind during tweetstorms (see below).

By “state of mind” I mean a recurring, discrete, cognitive, emotional, and physiological condition of being in which an individual perceives, thinks, responds, and relates in a distinctive manner for a finite period. Frequent observers often have shorthand ways to describe a person’s recurring problematic states of mind — e.g., “he’s having another one of his hissy fits.”

The power of certain states of mind to profoundly shape an individual’s salient associations and responses to sensitive stimuli or emotive contexts is most apparent when the person’s state of mind is extreme, e.g., blind rage, or is suddenly radically different from an immediately preceding state of mind, e.g., a sudden-onset panic attack. But waking, sleeping, working, playing, loving, or even comatose, we are always in some state of mind.

Typically, mental states cycle naturally in accordance with daily tasks and familiar contexts influencing how we think, feel, and act largely out of our awareness. It is only when the “normal” flow of mental states is derailed that we witness how painful, dysfunctional, hyperemotional, or traumatic states of mind (e.g., deep depression, explosive anger, traumatic grief, blind terror) globally influence perception, thinking, and behavior.

The clinical study of unusual mental states (e.g., fugue, hypnosis, catatonia, and abreactions) was a major focus of early psychiatry and psychology.3 Modern research on different types of mental states (e.g., sleep, hypnosis, panic attacks, catatonia, depression, mania, intoxication, psychedelics, meditation, dissociation, daydreaming, flashbacks, coma) identify variables that can used to operationally define the mental and physical dimensions of “stateness.”4

These include physiological measures such as heart rate, vagal tone, and other cardiac measures, galvanic skin response, hormone levels, and electrical, magnetic, and metabolic brain activation patterns. Psychological dimensions include level of arousal, affect, access to specific memories or learned skills, degree of self-awareness, reality testing, and attentional focus.

A key feature of discrete states of mind is their “state-dependency”( i.e., the selective compartmentalization of memories, cognitive associations, specific affects, and distinctive behaviors associated with a particular mental state). In general, the more extreme the mental state, the more complete the degree of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral compartmentalization. The more frequently a certain mental state reoccurs, the more easily it is re-elicited by situations and cues reminiscent of past triggers. In the same way that repeated bouts of bipolar mood swings progressively sensitize or “kindle” an individual reducing the threshold for future episodes, recurring tweetstorm increase the likelihood of more frequent and more intense tweetstorms in response to ever lower thresholds of provocation.

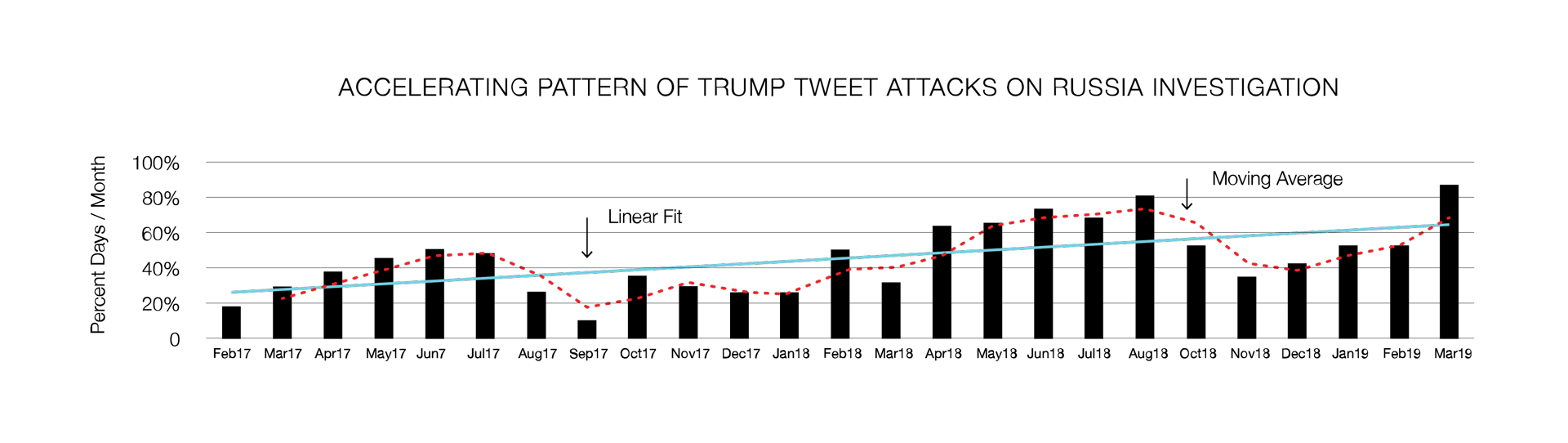

The NYT graphics2 plot the number of attacks by Trump each month on different institutions (e.g., DOJ, intelligence agencies, news media), individuals (e.g., Comey, Clinton) and investigations (Russia). Simple inspection of the NYT graphs reveals an escalating pattern of attacks across the board with notable jumps in certain topics proximal to salient events (e.g., Flynn pleads guilty, Comey’s book published, Manafort convicted).

Drawing on data in the NYT articles, the figure below plots the percentage of days in each month that the president tweeted one or more attacks on the Russia investigation. The solid straight line is a linear fit and the dotted curved line is a moving average. The linear fit documents the progressive escalation of attacks on the Russia investigation over two years.

The moving average reveals an accelerating pattern of periodic multi-month clusters of increased attacks.

The differences between 2017 and 2018 are striking. Only once prior to January 2018 did the president tweet attacks on 50% or more days of a month (June 2017). After January 2018, he tweeted attacks on 50% or more days in most months (8/12). More telling are the number of times in which tweet attacks continued for five or more consecutive days. Again, only once in 2017 did he tweet attacks on the Russia investigation for five or more consecutive days (July 22–27, 2017). In 2018, however, there were 13 occasions in which he attacked the Russia investigation for five or more days running. The longest sequence was 18 consecutive days from August 9 to August 26, 2018.

Accelerating Pattern of Trump Tweet Attacks on Russia Investigation

Although presidential states of mind and demeanor during tweetstorms are not well documented, an analogous venue of presidential mass communication, rallies, and speeches is observable. In both venues, Trump’s intended audiences include the same people.

Trump’s two-plus-hour speech to the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) (3/2/2019) is an example of tweet-related presidential states of mind on display. The single longest presidential speech of modern times, it was described by commentators as “bizarre,” “unhinged,” “crazy,” and evidence that he was not psychologically fit for office. Noting earlier in the speech that he was going “totally off script,” Trump shows a glimmer of insight observing later, “I’m going to regret this speech.”

The CPAC speech largely reprises the collective content of TTs, reaching all the way back to inaugural crowd size. The live audience’s boisterous appreciation of old tropes embedded in a fragmented, rambling, emotional narrative no doubt changed some of the psychological dynamics. But the reality distortion, ubiquitous outright lies, paranoia, threats, illogic, tangential leaps, inappropriate anecdotes, and dearth of empathy characteristic of presidential tweetstorms is also central to his live communications, reflecting similar states of mind.

Temporal analyses of TTs shows that over the past two years these disturbed states of mind are occurring ever more frequently.

So where does this go from here? What does 2019 hold? The two-year trends predict that the attacks and tweetstorms are going to continue to increase, probably even more rapidly than before. Research on predictors of psychological decompensation (often using violence as an outcome) finds that an accelerating pattern of emotional lability is a very concerning sign.4 There is good reason to believe that the stressors responsible for the 2018 surge in tweet attacks will only intensify, further compounded by new investigations that now threaten his family and business. Recently Trump tweeted his most overt threat of violence yet, implying that his supporters in the police, military, and Bikers for Trump could be “tough” on his foes (tweet was later deleted but is in the archive). This accelerating pattern of TTs traces an ominous psychological trajectory, one often associated with psychological decompensation and violence. The walls are closing in — what happens when Trump can’t take it any longer? ■

-

Frank W. Putnam, MD, is a professor psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is a child and adolescent psychiatrist specializing in the psychological and biological effects of maltreatment on child development. He is the author of over 200 research papers and three books on the lifelong effects of child maltreatment. His most recent book, The Way We Are: How States of Mind Influence our Identities, Personality and Potential for Change, New York, IP Books, investigates the biological and psychological processes shared by radically disparate mental states ranging from meditation to catatonia.

-

Email: frank_putnam@med.unc.edu

-

(1) Mark Mazzetti, Maggie Haberman, Nicholas Fandos and Michael S. Schmidt. “Inside Trump’s Two-Year War on the Investigations Encircling Him,” New York Times, Feb 19, 2019.

-

(2) Larry Buchanan and Karen Yourish. “Trump as Publicly Attacked the Russia Investigation More Than 1,100 Times,” New York Times, Feb, 19, 2019.

-

(3) Henri F. Ellenberger (1970). The Discovery of The Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books, New York.

-

(4) Putnam, Frank (2016). The Way We Are: How States of Mind Influence Our Identities, Personality and Potential for Change. IPBooks, New York.

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |