REMAINING TO BE SEEN

by Umi Chong

It is Tuesday at 4:00 pm, and it is time for Ben, a white man in his early thirties. He often refers to himself as “strange” for feeling out of step in not holding popular, mainstream views like most of his friends. He feels like that is due to a lack in him, and this lack makes him feel on the outside of things. He does not feel lacking or strange to me but familiar. I find myself holding him in warmth and fondness.

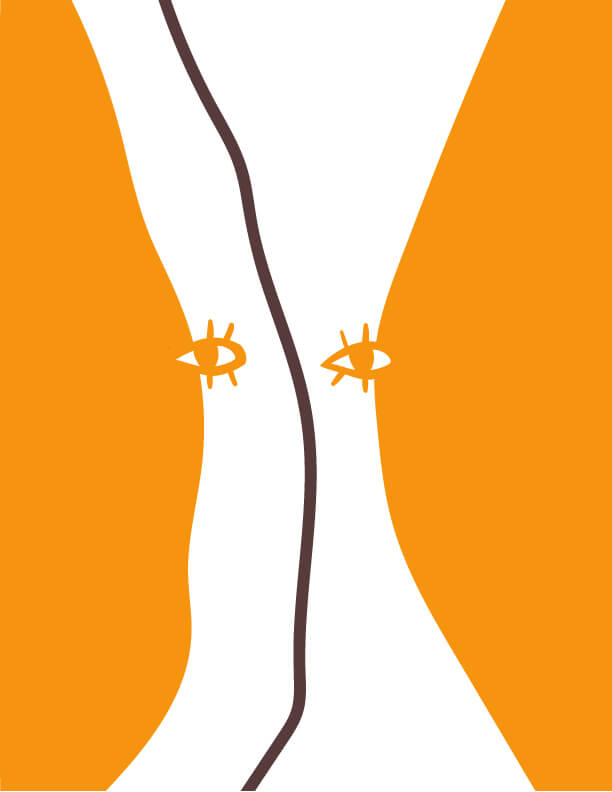

It is our first session of the week. He recounts a conversation he had with friends. It is about the rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans and how these hate crimes are not getting enough news coverage. Then he asks me, “Dr. Chong, are you okay? How are you doing with all this?” In that instance, I feel simultaneously seen and wanting to remain unseen. Both positions feel vulnerable to me.

I can feel my emotions well up. I am relieved we are on the phone and Ben cannot see my eyes tearing up. There is so much. How I want to answer is so vastly far from how I need to answer. That is when my mind goes to thoughts that have been banging around my head since my own analytic session on Friday and the weekend plenaries at the American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) meeting.

It would be too much to share my painful anguish, now having to process a racial enactment that my analyst and I are coming out of and starting to understand together. How do I convey that it seems without my body and phenotype in plain sight, in only hearing my voice, my Asian-ness seems to disappear? I have become white. But more than that, I am being centered in whiteness, and being constructed against the norms of it—and my lack of it. It is an agonizing and grueling process to become visible because it entails decentering my analyst’s whiteness. I start decentering by having the courage, and the nerve, to say in response, “So thinks and says the white man.”

This lack of representation remains as I search for Asian-ness in the APsaA plenaries. The generalities along with the particular aspects of being a racialized object, seems limited to the Black and Brown experience. And, now, finally in the mix, whiteness has arrived at APsaA, rightfully taking its place as the racializing subject. whiteness is no longer being held invisible. But where is my Yellowness among Black, Brown, and white? It feels like I have been subsumed as part of one of these groups or have been made invisible again.

Within the Asian American community, there is a hyperawareness about not being seen. And that this impoverishment can begin to feed on itself and even become protective, as it did for my parents and previous immigrant generations. For them, they felt being visible was a vulnerability and weakness—why expose and risk yourself to be seen, given the uncertainty of how your humanness will be responded to beyond our sheltered enclaves? For me, vulnerability in this racial context is a paradox—it is because of this uncertainty that it is safer and necessary to be visible, to emotionally show myself, and to want to be fully seen and heard. That is to be fully represented in the particular ways my humanness is racialized as an Asian American—if only for the opportunity to relinquish these ghosts from my own mind, let alone for my generation.

My mind returns to Ben. He wants to see me and inquires about the current state of my racial condition. In a mixed tone of gratitude and anguish, I share it has been painful to see these awful racial crimes transpire and how they have gone on too long, and so overlooked. I feel his asking helps, and it shows me he wants to make things better. But I know there is vulnerability, too, in his asking me his question. There is a part of him that wants to be visible.

We are well into the hour. I turn my attention to Ben, as he tells me about his lack of being seen as a particular kind of white man. A white man who is at odds with his community in searching for what the notion of whiteness means and entails, while at the same time, he is deeply at odds within himself, grappling to come to terms with how whiteness is being characterized by others.

How our work ahead takes shape—to find the words to fathom what has been impoverished and to fully represent our humanness in the process—remains to be seen. ■

-

Umi Chong, MBE, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist and a third-year candidate at the Washington Baltimore Center for Psychoanalysis. She has a private practice in Washington, DC, working with adults from various sociocultural backgrounds. Her area of interests include the Kleinian philosophy of mind, race and cultural identity issues, and bioethics.

-

Email: umichong.psyd@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |