The Wallet

by Douglas H. White

In the fall of 1948, in the small town of Kinston, North Carolina, a six-year-old Black boy wandered out of a drab project building where he lived with his family, to a schoolyard to play with other neighborhood boys. He was wearing a small brown cap with a chin strap, corduroy trousers with patches his mother had stitched on the knees, and a red flannel jacket with six large black buttons down the front. His brother Ricky had outgrown the red jacket, and his mother did not want to buy another piece of clothing from Sears and Roebuck, even shouting out at times, “No mo’ Sears and Roebuck.”

The little boy was excited to get to the schoolyard to play with his friends Sam, Mitch, Kellis, Otha, JD, and Melvin. The yard was part of a mission school for Black children run by the Franciscans of the Catholic Church. In this largely Black Protestant community, the nuns and priests sought to convert Black families, to educate and teach the children the Catholic way. His mother converted to Catholicism the year he was born, and the boy was baptized soon thereafter. His mother knew she wanted her children enrolled in the segregated Catholic school because she believed the education was superior to the public segregated elementary school. Adjacent to the schoolyard was a three-story red brick convent where the nuns of the Order of the Most Precious Blood lived. The priests lived nearby in a two-story brick house. All the nuns and priests who operated Our Lady of the Atonement Catholic Church and School were white. The schoolyard was a dirt field, and at one corner of the field was a large six-swing apparatus situated over a sand pit.

The little boy had fun playing football with the other boys, but then he made his way over to his favorite place, the swings, to feel like a free bird, the wind against his face. There he stayed for an hour, pushing himself higher and higher until the swing started to buckle and twist. Then he would stop pumping the swing, slow down and jump into the sand. This day, his foot struck something hard. He reached his little hand into the sand and felt something that felt like leather. When he pulled out his discovery, he found it was a black wallet. He opened the wallet and saw a photo of a nun dressed in a full black habit staring at him. The six-year-old attended the Catholic school but did not recognize the nun in the picture. He stared at it for a few minutes, then ran over to the convent house, knocking vigorously on the door.

After a while, a nun came to the door and said sharply to the child, “Yes?” She looked like the nun in the wallet photo.

The little boy smiled, happy with himself. “I found the wallet in the sand by the swing,” he said, and he reached up to hand it to the nun.

But she snatched the wallet from his hand, quickly looked through its pockets, and snarled, “Where is the money? Did you steal it? Give it to me.”

The little boy said, “I found it under the swing in the sand. I don’t have no money.”

The nun stared at the six-year-old. Her penetrating blue eyes caused the child to look away and start to cry. He said nothing but felt hurt, offended, and disliked; then another nun, Sister Gertrude, who was the boy’s teacher, came to the door, assessed the situation and said, “He is a good boy. He would not steal your money.”

On the way home that day the little boy was lost in thought, confused about what happened. His eyes welled up with tears, causing him to stumble as he walked, and with every step he took filtering through his mind were other moments: the time his mother hushed him up on the Washington Street bus when he asked her why they could not sit up front where the seats were empty rather than stand in the rear; the time she told him, her eyes blazing with defiance, not to drink at the colored or the white water fountain at the Sears and Roebuck store, her pride taking precedence over thirst.

The little boy also remembered what his friend Joe Dixon always said about white people: “Don’t trust ’em.” All of these reflections and more passed through his mind on the four-block walk to his home, but what struck him most forcefully was the reason he had been treated that way by the nun: he was Black and she was white. He knew right then he did not want to live in a place where this could happen to him, but where could he go? Something was wrong and he did not understand it. Would he understand it when he was older? He tried not to think of these bad things at all because it did not help.

When he arrived at the front door of his home, he carefully wiped the tears and snot from his eyes and nose on the sleeves of his hand-me-down jacket, although he knew his mother would not approve if she observed the dried snot on the jacket. He did not speak of the incident to anyone in his family; he felt ashamed. That little boy was me.

With the passing of early childhood and not speaking of the incident to anyone, the wallet story became buried in my consciousness.

Thirty-five years later, I had become a Yale-educated lawyer and, under Governor Mario Cuomo, the Commissioner of Human Rights for the state of New York. In 1984, after a meeting of the members of the Black/Jewish Coalition, a group addressing the tensions of Blacks and Jews in New York City, the participants began a discussion about how they dealt with racism and anti-Semitism in their own lives. The Black/Jewish Coalition was composed of sixty people representing, among others, the NAACP, Urban League, American Jewish Committee, American Jewish Congress, and One Hundred Black Men. The aim of the coalition was to disavow rhetoric that divides the Black and Jewish communities, focusing on mutual concerns and emphasizing our many experiences of mutual support and assistance. Founding members included Rabbi Balfour Bricker, Stephen Wise Synagogue; Wilbert Tatum, Editor of the Amsterdam News; Stanley H. Lowell, former deputy mayor of New York City; Hazel Dukes, president of the New York State Conference of the NAACP; David Dinkins, New York City clerk and future mayor of New York City; Letty Pogrebin, writer and editor; Basil Patterson, a former city and state official; H. Carl McCall, a former New York State senator; and Dr. Roscoe Brown, famed Tuskegee Airman.

Although I had been confronted by racism many times in my life, including being beaten, arrested, and jailed in a civil rights demonstration against segregation and Jim Crow in Durham, North Carolina, in 1963, I did not know what I would say when my turn came to speak. But seemingly from nowhere, the wallet story tumbled out of my mouth between stops and starts, and to my shock—I was crying. I had forgotten the wallet story until I began to tell it. Why was I crying? I did not cry easily. All the participants supported me with encouraging words and hugs, but the one I remember most was a Black participant in the group, Dr. Roscoe Brown, who had been a squadron commander of the Tuskegee Airmen and a good friend. He calmed me, saying, “It’s alright to cry, brother.” Roscoe’s comment meant a lot to me in part because he was my father’s age, and as a Black man of the previous generation, he had seen and felt even worse racism than I had.

I had pushed this past event so deep into my gut that it had never come out before this meeting, the unconscious hurt lying dormant for thirty-five years. At six years old, a white person had made me feel ashamed that I had done something wrong when in fact I was being exemplary. The penetrating blue eyes of the nun caused me to feel insignificant, that being Black was bad. The words of the nun, “Did you steal it?” would follow me for the rest of my life. The defense of deciding not to “see” or remember is not a solution for dealing with racism; it never was and never will be.

I realize now that I am composed of the full inventory of the slights and dehumanizing aspects of racism I have known. But why did this story return so suddenly? Was it because many people were talking about racism and anti-Semitism? Why did this early event cause so much anguish and trauma in me thirty-five years after it happened? Was it because all nuns represented a kind of goodness in my six-year-old mind, a goodness that was shattered in an instant?

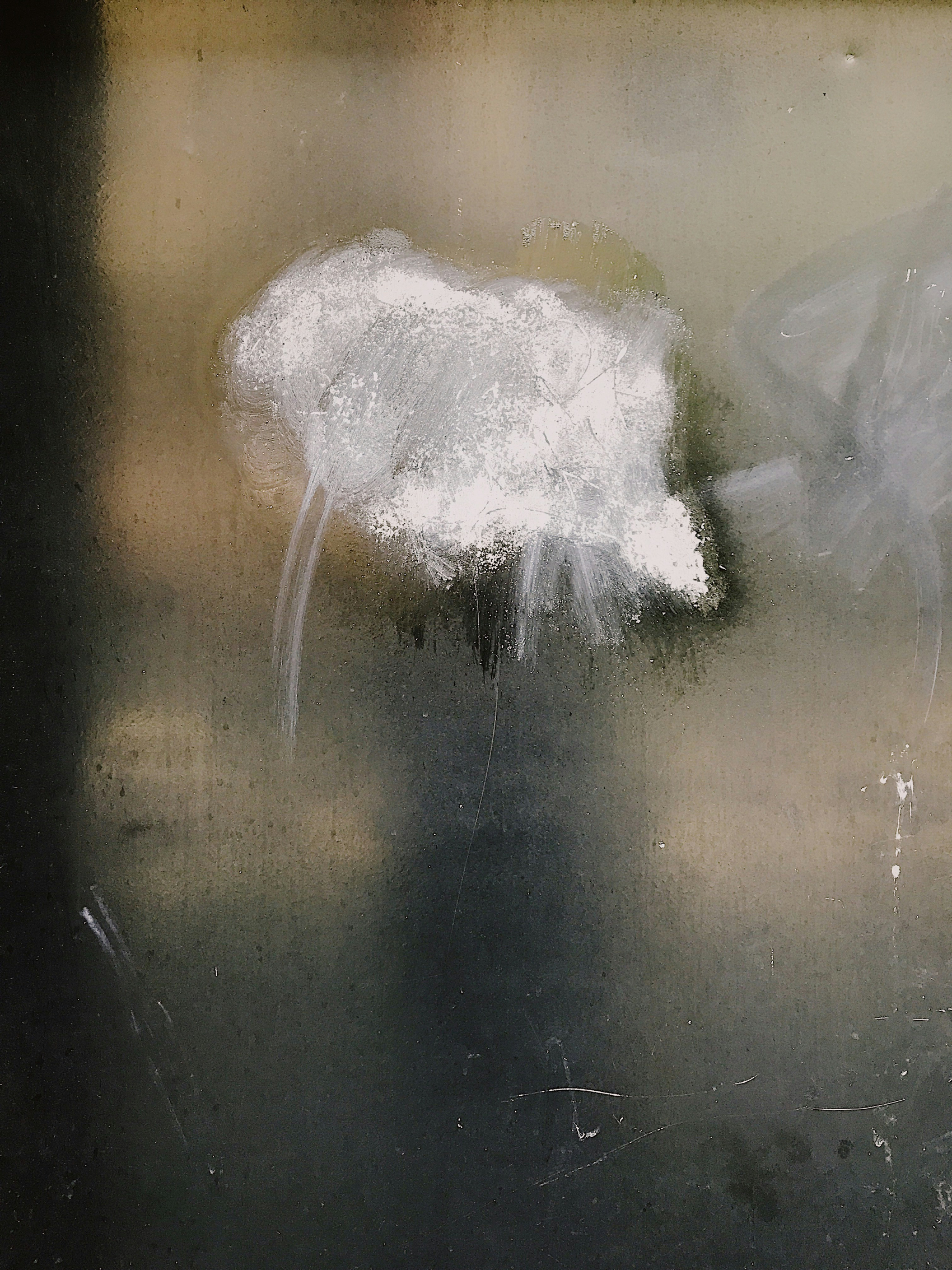

This moment signified a storm cloud of racism taking shape in my early years that would cover my entire life. The lesson of my childhood was this: if you ventured too far from the intimate Black world, you would be slapped down. This incident was paradigmatic of the humiliations visited upon Black people across America every second of every day, both then and now.

As I reflect on my comfort level in the Black/Jewish meeting, I believe my crying occurred because I was drawn to the poignant stories recounted by others in facing racism and anti-Semitism in their lives and the lives of their families. I worked with many of the people in the Coalition on many issues and knew we shared a desire for a better future free of discrimination. The stories we told of our hurt, sadness, and affronts to our dignity gave these moments a power that would not have been present if we were not reflecting together.

***

Growing up in Kinston, North Carolina, I am part of the last generation of Black Americans born under the noxious segregation and Jim Crow laws in the American South. As a child, I did not envision being a lawyer or activist in the future. However, my brother Simeon and several of my friends, Sam, Kellis, and James, must have been traveling the same paths in their minds because we all became activists and lawyers engaged in the struggle for freedom for Black people.

Now, as I reflect on the wallet story, I feel the stress I must have felt as a six-year-old when the nun said, “Did you steal it?” I contrast this incident with when I was a twenty-year-old college student and I, along with fifteen others, demonstrated in front of a segregated Holiday Inn in Durham, North Carolina. When we ran into the Holiday Inn, the police beat us with billy clubs and truncheons, arrested us, and marched us off to jail.

Unlike my experience with the nun when I was a child, as an adolescent, this confrontation with the police empowered me for the rest of my life. Those billy clubs and the vicious taunts, “Get the niggers,” striking my body strengthened my mind and convinced me that we could overcome segregation and Jim Crow, causing me to be less afraid and more confident.

My life has taught me that activism against racism, xenophobia, and authoritarianism will embolden us, give us power, and create a sense of strength and courage.

- Douglas H. White is a civil rights activist, lawyer, and government official whose career has centered on human and civil rights and labor law. He was Human Rights Commissioner for the State of New York, City Personnel Director / Commissioner of the City of New York, and Deputy Fire Commissioner for New York City. He recently completed a memoir entitled Unbroken: The Last Generation of Black Americans Under Jim Crow and the Culture of Racism in America. The memoir is represented by Marie Brown Associates.

- Email: douglashugheswhite@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |