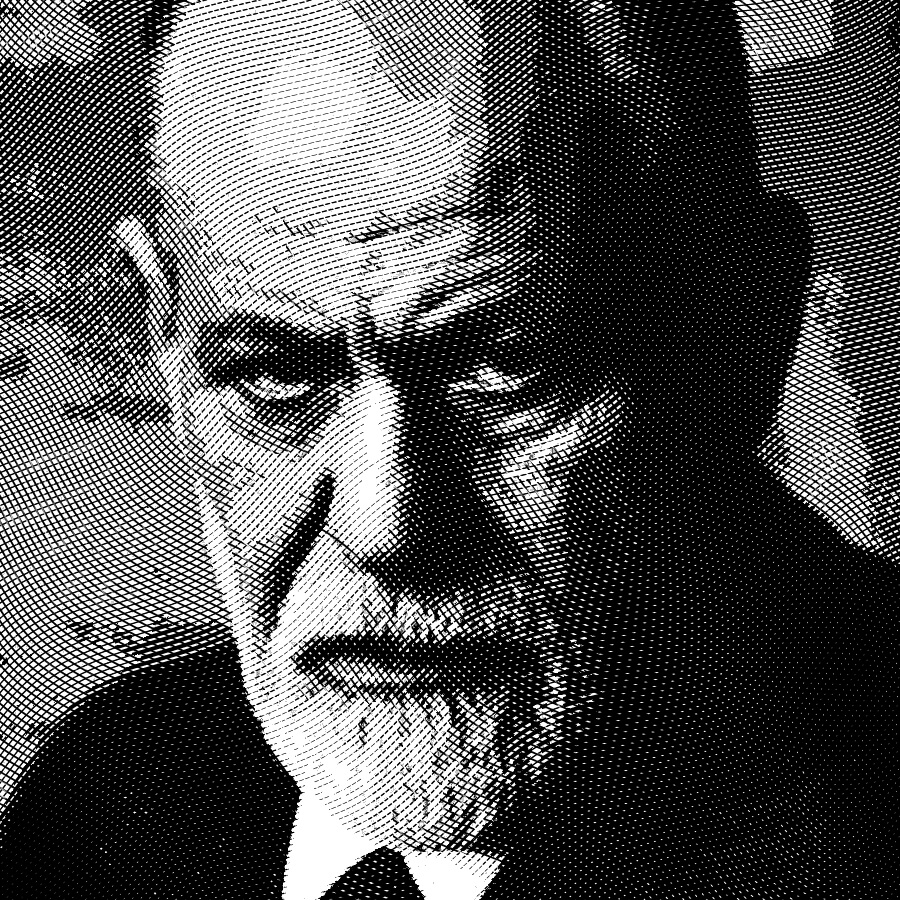

#USTOO, SIGMUND

by Elizabeth Cutter Evert

I am writing in the spirit of #MeToo to bear witness to damage that has been done to a subset of women I have known personally in my thirty years of practice as a psychoanalyst, who felt pressured by the value placed on sexuality in the cultural milieu of the 1960s and, 70s and in the psychoanalytic circles they came to for help. I am also writing because I think these women’s stories offer a window into ways the mid-to-late-twentieth-century sexual revolution was experienced differently in various parts of the United States. This inquiry is part of a larger project, where I have been exploring ways to bridge cultural divides that block collaboration on a humanitarian political agenda.

In the 1950s mainstream psychoanalytic theory held that we resolve issues with dependency early, so as to be able to emerge capable of autonomy and sexual pleasure. The healthiest patients were seen as those who struggled with derivatives of Oedipal conflict; others might or might not be analyzable. In this cultural and therapeutic milieu, women who functioned well in a number of areas but who struggled with sexual arousal often believed that their erotic difficulties were causing their emotional problems. Where sexual experience and freedom were privileged over attachment and other emotional needs, these women found themselves confused and alienated from themselves — both sexually and, sometimes, in terms of a basic sense of self.

At the turn of the century, Freud saw the inhibition of sexual outlets as the primary cause of neurosis, the overvaluation of sexual acts, and the failure to recognize the importance of human interconnection, which became out of line when Freud abandoned his seduction theory. The early Freudian view does not fit with our contemporary understanding of physio-emotional needs and with what we now know about how sexuality works. Nevertheless, the notion of sexual inhibition as the root of psychiatric difficulty had entered the popular imagination, and for decades psychoanalysis lent medical authority to this cultural strand. People who only knew psychoanalysis from the movies were likely to think of it as involving a couch and a scintillating emphasis on a link between erotic and psychological issues. Psychoanalytic ideas about the importance of freeing our sexual experience continued to permeate through the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. (Zaretsky) In many circles, prevailing psychoanalytic theory held that we that resolve pre-Oedipal issues early, so as to be able to emerge capable of freedom and sexual pleasure.

For a subset of women struggling with a sense of self, this kind of therapeutic situation became more damaging. I am speaking of those who often do relatively well in the world but feel empty or like they are “going through the motions.” In a core way, they may not know who they are. When someone in a state like this came to a therapist for help and the main interpretive line had to do with sexuality, they sometimes doubted themselves further. Feeling hazy to begin with, some sensitized themselves to the sexual, while going underground with their loneliness and doubt. Others may have developed an almost Stockholm-syndrome-like cycle, where they intensified their bond to the therapist, tried harder to “do analysis right,” and became further alienated from themselves. Perhaps the memory of these early analyses should be an #UsToo moment for psychoanalysis, even where explicit boundary violations did not occur.

Where most contemporary analysts combine object relational, intersubjective, and other theories with classical analytic understanding, it would be comfortable to turn the page on this chapter of our history. But women and men who feel unsure of themselves as they worry about sexuality are very much with us today. Loneliness is prevalent; even preteens scan the internet for porn they hope will prepare them to be adequate as they mature. In an age of global interconnectivity, individuals around the world wrestle with sexual values that clash with deeply held cultural and spiritual beliefs.

Neuropsychology, Narcissism, and Sexuality

We know that children need secure attachments to their primary caregivers to develop the capacity for curiosity and imaginative play. Without it, they spend their energy coping with feelings of fear, anger, and abandonment, as Bessel van der Kolk describes in The Body Keeps the Score, his 2014 compilation of research on the neuropsychological results of trauma and the spectrum of childhood abuse and neglect. Bowlby saw a need for attachment figures throughout life. Van der Kolk describes that while “our culture teaches us to focus on personal uniqueness, at a deeper level we barely exist as individual organisms. Our brains are built to help us function as members of a tribe.” (80)

Van der Kolk looks at individuals for whom a sense of self is missing from a neuropsychological point of view. He describes that, most of the time, we live in a state of “background functioning,” where we integrate what we experience in our bodies, our minds, and in the world. We are capable of empathy, thought, creativity, and a resonant sense of self. Infant observation teaches us that this background interconnection develops in early dyadic exchanges with the mother and other caregivers. In emergencies, though, this background functioning shuts down, and we enter fight, flight, and freeze modalities. As we know from descriptions from people who have experienced rape or other trauma, it is common to dissociate and to experience being outside of oneself, watching what is transpiring from above.

In PTSD, and for many survivors of childhood abuse and neglect, seemingly insignificant events, thoughts, or feelings trigger emergency reactions, which seem to exist on a spectrum of severity. It is possible for people who grow up in relatively stable homes where there is significant ambivalence about attachment needs or where there are chronic situations of mild but confusing overstimulation to bounce between rage, avoidance, and hazy or unreal shut-down states. Their capacity to feel a background sense of who they are can be minimal. It seems understandable that, for these women, intense involvement with a therapist who focused on sexual repression would be counterproductive.

From Emily Nagoski’s bestselling 2015 compilation of research on female sexuality, Come As You Are, we learn that it was also unlikely to improve their sexual functioning. She describes that, like problems with experiencing a sense of self, most difficulties in sexual arousal are connected to fight, flight, or freeze reactions, often set off by barely conscious emotional reactions. She writes of several sexually compatible couples where the woman found herself unable to be interested in sex once she was balancing work, childcare, and marriage. Experiencing herself as failing to keep up sexually, professionally, as a wife, or as a mother, she reflexively lashes out, withdraws, or shuts down. Lonely and worried about herself, the patterns become ingrained. If she were to go to a therapist likely to interpret a range of emotional problems in sexual terms, she may feel she does not know her mind or body, and the dissociation could grow more intense.

Nagoski also describes that, until the 1990s, much of our understanding of the female sexual response came from Masters and Johnson’s studies of women masturbating and having intercourse in a laboratory setting. We learned a lot about the stages of arousal. The psychoanalytic gold standard of vaginal orgasm was replaced by a fuller understanding of the importance of the clitoris. However, the bar for what is sexually normal for women was reset. Women began to worry about frigidity if enjoying sex in public or with strangers seemed out of reach.

Current research indicates that resonant sexual experience is connected with an individual’s capacity to experience deep attachment comfortably. Sue Johnson writes about attachment style and both sexual motivation and satisfaction. She describes individuals with an avoidant attachment style as more likely to have what I term “sealed-off sex.” The focus here is on one’s own sensations. Sex is self-centered and self-affirming, a performance aimed at achieving climax and confirming one’s own sexual skill. Those with more anxious attachment tend to have “solace sex”, that is, to use sex as proof of how much they are loved. Sealed-off sex tends to be erotic but empty, while solace sex is soothing but unerotic. The most satisfying sex occurs when partners are securely attached.

It is important not to read the research as demonstrating the superiority of sexual experience in committed relationships. The studies Johnson quotes are about attachment style (avoidant, anxious, or secure) of the individuals involved, rather than the status of the liaison.

Conclusion: The Body Politic

Fortunately, #UsToo does not have to be the end of the story. Therapist and patient can come to understand times where emotional needs and cultural assumptions have woven together to create emotional cycles in the therapeutic dyad. Van der Kolk, Nagoski, and Johnson write about the possibility of building new neurological pathways. Attachment styles are mutable. There are a myriad of therapeutic, artistic, social, spiritual, and body-based ways to change the balance between emergency and background functioning. Both sexuality and a sense of self seem to regenerate when we feel grounded in our bodies and in our worlds.

Both globally and in this country, as we navigate our fractured cultural terrains, it seems important to approach each other with curiosity, caution, and respect. When theoretical orthodoxy has dominated the psychoanalytic space, people have suffered. Perhaps there is some hope in the possibility of drawing on the appreciation of depth and dignity that is foundational for a range of psychoanalytic, humanist, and religious traditions. ■

-

Elizabeth Cutter Evert, LCSW, is a psychoanalyst in private practice in New York City. She is on the clinical faculty of IPTAR and is a director of their Clinical Center. She is interested in questions of female development and in the overlap between secular and religious experience.

-

Email: elizcutterevert@gmail.com

-

Johnson, S. 2013. Love Sense. New York: Little, Brown Spark.

-

Nagoski, E. 2015. Come As You Are. New York: Simon and Schuster.

-

Van der Kolk, B. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Penguin Books.

-

Zaretsky, E. 2017. Political Freud: A History. New York: Columbia University Press.

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |