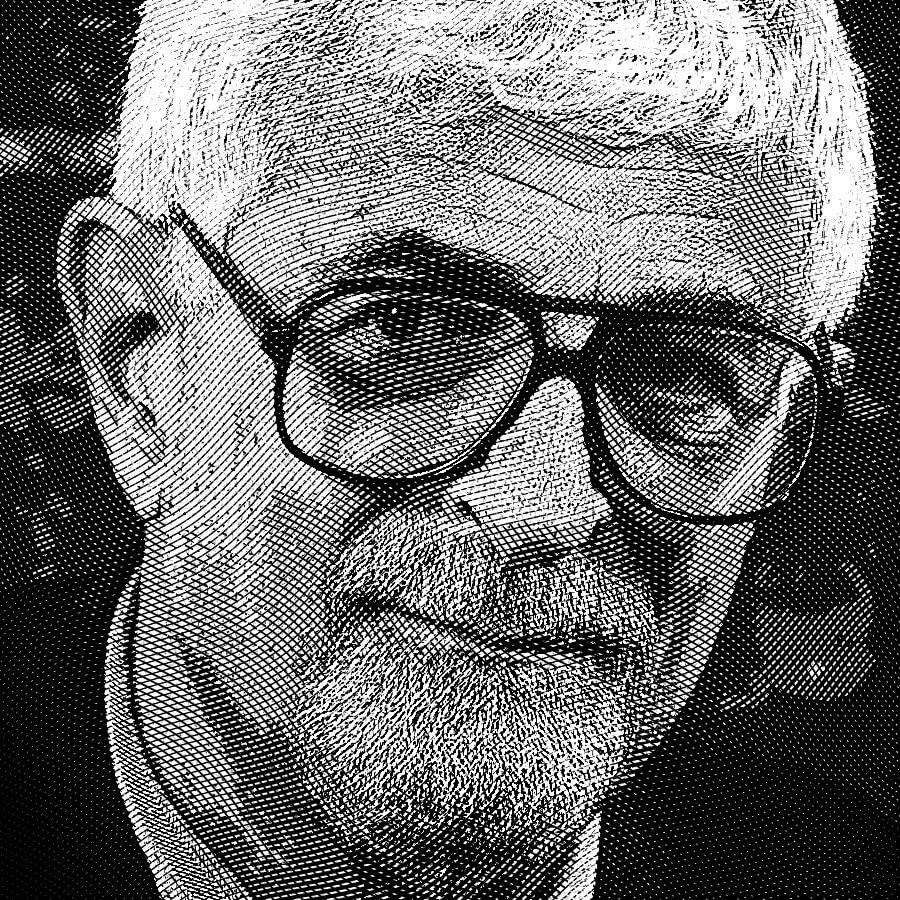

VAMIK VOLKAN: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION

by Richard Grosse

Vamik Volkan was born in 1932 in a Turkish family on Cyprus, received his medical education in Turkey, and trained in psychiatry and psychoanalysis in the United States. From a career in psychoanalysis in which he published many papers, he eventually found his way to creating a discipline in the application of psychoanalytic ideas to international conflict. Over the course of several decades, he has founded two institutions and a journal, met and often befriended world leaders, and, perhaps most importantly, developed a series of concepts that allow us to use psychoanalytic approaches to think about the large group processes that are so important in understanding conflicts among nations and groups.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Dr. Volkan for more than an hour recently, during which I received something of an introduction to his career and his thought. This is a brief summary of what I learned.

Dr. Volkan’s distinguished career in mediating and understanding international disputes seems prefigured by — and perhaps can be seen as originating in — the fact that he was born on Cyprus, an island that has experienced ethnic tensions between its Turkish and Greek populations for centuries. It is striking that, being raised on a small island long wracked by conflict between two nationalities, after working in medicine, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis, Volkan made it his life’s work helping world leaders understand the international tensions that they deal with and creating an intellectual discipline for understanding those tensions.

The sense of a man inexorably finding his way to his life’s work is underlined by the fact that a series of external events and accidents played a large role in the beginning of his career. His interest in international relations had already won him a place on the Committee on Psychiatry and International Relations of the American Psychiatric Association, when Anwar Sadat stood the Middle East on its head in 1977 and, from the Israeli parliament, the Knesset, announced among other things that 70% of the difficulties between Arabs and Israelis were due to the “psychological wall” between them. Taking his statement seriously, the American government approached the aforementioned committee to investigate this “wall” that Sadat said was so important. Three years into the work of bringing Israelis and first Egyptians and then Palestinians together to talk about their differences, Volkan received a phone call in the middle of the night asking him to lead the work of the committee. To this day, he doesn’t know what prompted that phone call, but it marked the beginning of his career as a diplomatic and cultural mediator and later a theorist of intergroup conflicts. In the next decade, he founded the Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction, to pursue the work of mediating and understanding international disputes. When Reagan and Gorbachev began their negotiations in the 1980s, Volkan’s Center became the primary institution for the exchange of psychologists and the investigation of the cultural tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union.

In retrospect, Volkan’s career can seem like the inevitable unfolding of a set of preoccupations, although each individual step at the time seemed like an accident or a response to external events.

His career has allowed him to observe closely the thinking and behavior of parties to the most difficult (and violent) international conflicts of our time: Arab—Israeli; Soviet Union-USA; Russia-Estonia, Georgia-South Ossetia, Serbia-Croatia, Turkey-Greece; Albania-Macedonia, to name a few. Through these years of observation and theory building, he developed the concept of Large Group Identity to describe the emotional ties that, he posits, all people have to the large group they identify with. Freud, he explained in our conversation, theorized the intrapsychic world to the neglect of the ties to the group, especially relations of members of one group to another group. Volkan sees Large Group Identity as being marked and, during conflicts, expressed by the “chosen traumas” and “chosen glories” of a group, moments of group trauma (e.g., the fall of Constantinople in 1453 for Greeks), and group glory (e.g., the defeat of the Ottomans and the ending of the Ottoman siege of Vienna on September 12, 1683, for Austrians), events in the distant past that become important symbols of group identity.

As an example of the power of Large Group Identity to wreck terrible destruction, Volkan could have mentioned the enthusiastic reaction of the vast majority of Europeans, on all sides, to the outbreak of World War I, which even included for the first six months of the war Sigmund Freud. Germany’s defeat and the punitive Treaty of Versailles, then, even though contemporaneous, became a chosen trauma for Germans, which was skillfully exploited by Hitler. Thus Volkan has produced a concept that allows us to understand the passions that rule groups in moments of crisis.

This brief introduction will not make the slightest attempt to sketch the length and depth of Dr. Volkan’s résumé, except to point out that his creativity has extended to founding two institutions for the organized pursuit of helping disputing parties come into dialogue with each other, the aforementioned Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction (1987–2002), and the International Dialogue Initiative, which he founded in 2007. In addition, he founded the journal Mind and Human Interaction. He was also invited by Jimmy Carter to be a member of Carter’s International Negotiation Network (1989–2000). In all of this work, Volkan has made rich use of basic psychoanalytic concepts such as transference, regression, adding his own concept of Large Group Identity, which has begun to be taught in psychoanalytic institutes.

Finally, to illustrate the personal (i.e., psychoanalytic) nature of his work, there are the relationships that are depicted in the recent film Vamik’s Room, by Molly Castelloe, which I asked Dr. Volkan about in our conversation. The film concerns a set of relationships that he cultivated with the people in what was essentially a refugee camp. They were Georgians who had been displaced from their homes in Abkhazia, a part of Georgia, during a conflict between Abkhazia and Georgia, who were housed in a large apartment building that was formerly a Soviet resort for high officials, but which was now, as he describes it, largely a garbage dump since the demoralized 3000 refugees residing there could not take care of their surroundings. He began by locating the individuals who he thought were the leading members of the group and settled on a couple who possessed the only telephone in the building. He began visiting them regularly, during which times he would talk to them about mourning their losses.

After several years of regular visits, changes started to happen. The wife began meeting with groups of her neighbors, and she talked with them about mourning. The father of the husband, a former philosophy professor, began writing a poem every day and reading it to his assembled neighbors. These poems expressed his sense of mourning. Slowly, the residents of the building began to clean it up. Groups formed to revive their cultural practices, one dedicated to singing traditional songs. And representing the psychological reconstruction that was going on, the residents built and furnished a room for Dr. Volkan, so he could stay there during his visits.

In our conversation, Dr. Volkan agreed that there had been a powerful transference from this couple to him and that this transference had stimulated a sense of self-worth that had gone out from them into the group in a kind of positive ripple effect. The couple felt that Dr. Volkan cared about them — after all, he came to see them on a regular basis multiple times a year for some years — and feeling cared about by this important foreigner helped them to start caring about themselves, which prompted them to help others care about themselves. In addition, they were having conversations about mourning that allowed them to put their grief into words, symbolizing it. One can suppose that Dr. Volkan has not achieved results like this every time he meets with angry, frightened, disturbed, or traumatized people. But this moving example shows how he works with people, combining the intimacy of the psychoanalytic encounter with a sophisticated knowledge of group dynamics.

It also shows how psychoanalytic concepts can play out in group situations, here how a powerful transference within a demoralized refugee group became something life giving and culture renewing. Looking at the long list of situations into which he has been invited, as well as the prizes and awards he has been given, we should, I think, look on his success in this case as an indication of the power of Dr. Volkan’s use of psychoanalytic concepts and techniques as applied to groups, including groups suffering from severe pathologies. Vamik Volkan in this way has achieved an important extension of psychoanalytic ideas into the realm of large group conflict and thereby into history. ■

-

Richard Grose, PhD, is an associate member of IPTAR, where he serves as secretary on the board of directors and teaches in the respecialization program. He is a member of ROOM’s editorial board and a co-chair of the Room Roundtable. He has a private practice in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis in Manhattan.

-

Email: groser@earthlink.net

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |