BOOK REVIEW

by Richard Grose

On The Pleasures of Owning Persons: The Hidden Face of American Slavery by Volney Gay

On the Pleasures of Owning Persons by Volney Gay (IP Books, 2016) is a book written for white Americans. The author is a professor in the Departments of Religious Studies, Psychiatry, and Anthropology at Vanderbilt University and is a training and supervising analyst at the St. Louis Psychoanalytic Institute. He employs what he calls “applied empathy” to give an account of the minds of American slaveowners through understanding the pleasures they derived from owning slaves and the ways in which they tried to deal with the contradiction between owning slaves and seeing themselves as freedom-loving Christians. He positions his book as part of the effort to understand the effects of hierarchies that the powerful have created, focusing here on the divided minds of the powerful.

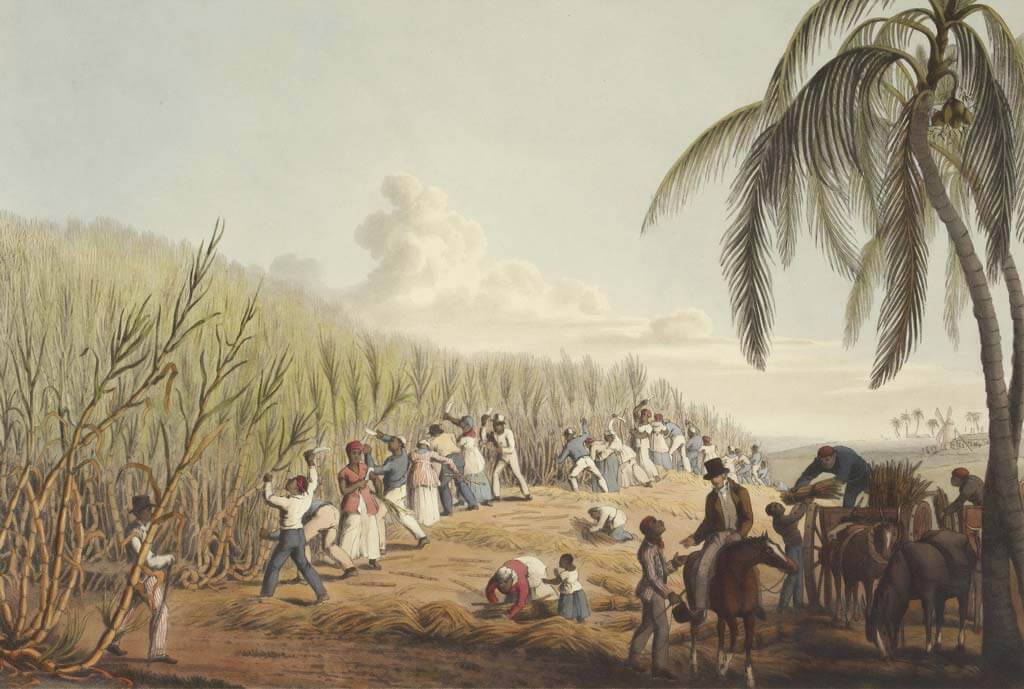

In simplest terms, On the Pleasures of Owning Persons is a look at the meaning of slavery in the United States as viewed by a very well-read psychoanalyst who is trained in understanding conflict and defense. The book has three parts: the facts of slavery, the contradiction contained in the US Constitution, and four different resolutions to this contradiction. That contradiction, deeply felt in the Founders’ debates on the 1787 Constitution and dominating national life until the end of the Civil War, with profound aftereffects extending into the present moment, was the bifurcated view of African slaves as both persons and property. As persons, they would be subject to the precepts of Christianity and those of the Declaration of Independence, beginning with “all men are created equal.” But as property, they had no more rights than horses and cattle.

Gay mentions the well-known misgivings that American heroes such as Washington, Jefferson, and Madison had about slavery, although their conflicts did not lead to emancipation during their lifetimes. But Gay is equally interested in our conflicts as we try to reconcile our reverence for a figure like Washington and his record as a slave owner. There are no easy resolutions to these conflicts: he tells us the story of Washington selling a rebellious slave named Tom to the West Indies, where slaves did not survive long. From the title and on through many parts of this book, there is much to make white Americans uncomfortable.

Gay discusses the ways in which Southern slavery apologists tried to resolve the inherent contradiction, from arguing that slavery civilizes and improves slaves to arguing that, although regrettable, slavery makes possible a very high level of culture that justifies it, among many others. He discusses the defensive idealizations that Southerners engaged in after the Civil War. They argued, falsely, that the war had not been fought for slavery but rather for the defense of Southern women. They also cultivated a rosy nostalgia for the Lost Cause.

Gay achieves something like an epic portrait of our profound national conflict, ranging from uneasy consciences to blatant fabrications and dissimulations by authorities, to rancorous legal disputes, to the awesome Civil War itself. There is something Tolstoyan about this portrait.

Before beginning his account of the pleasures of owning slaves, Gay describes how he has benefited from white privilege. He gives us a brief autobiography, recounting how he began life in a struggling lower-class family but found his way up by means of voracious reading and hard work, becoming a professor in multiple university departments. Specifically, he always felt at home with his white teachers, he never felt malice directed toward him, he didn’t have to contend with shame for ancestors, and he always felt and was allowed to feel entitled to his success. He also shows how much easier it was for him and his wife to begin middle-class life than it has been for very many African Americans. Thus, his discussion of the everyday pleasures of slave ownership begins with an analysis of the dependence of his everyday pleasures on white privilege. He lets his white readers draw whatever parallels they may.

He does not do this, but for the purposes of this review, I will group the pleasures he describes of slave owning into four categories: social pleasures—being admired socially, feeling you are a member of an elite, knowing that however far you fall, there are those who will always be lower than you; domestic pleasures—being served, being treated with respect, affection, and even love, having many people working for your betterment, having abundant free time for leisure activities, play, and culture; economic pleasures—knowing that your wealth will steadily increase as your slaves reproduce; and sadistic pleasures—knowing that you have complete control over the minds, bodies, and spirits of other human beings.

Gay argues that only by understanding the many pleasures that slavery brought to slave-owning families can we ever understand why it was so deeply rooted, costing so very much when it was uprooted and leaving so many persistent traces—no merely economic arrangement would have generated this scale of ferocious attachment.

It bears mentioning that his account of the pleasures of slave owning owes much to the account of pleasures in psychoanalysis. Gay calls on his white readers to consider pleasure as pleasure regardless of the moral judgments that can be made, in just the same way that Freud called on his scientific readers to do a very similar thing in his discussions of the pleasures of sexuality. For both, setting aside conventional moral judgments makes it possible to think about the meanings of pleasure.

Gay describes his book as “an essay in applied empathy.” He goes on: “It is based on the assumption that the better we understand slave owners, the better we understand our shared history. To do that we must conceive of ourselves in their circumstances, making their choices, using reasons and justifications that felt valid to them.” It is important to acknowledge, however obvious it may be, that Gay is empathizing with individuals who were committing what he elsewhere calls “a great crime and a great sin.” The first thing to notice here is that there can only be applied empathy for slave owners if the pleasures of moral judgment and moral distancing are suppressed and our common humanity is affirmed. This seems to be both a logical precondition for any knowing of the other, as well as a moral good, acting against a cultivation of moral superiority and the emotional isolation that can accompany that state.

This application of empathy also implicates psychoanalysis. Freud offered his patients a place where everything they said would be received empathically, that is, without judgment. Gay is applying that principle to our national history. There is no patient here, but the principle of nonjudgmental empathy is applied for the same purpose as it is applied in the consulting room: to achieve greater understanding.

Interestingly, the model for applied empathy was perhaps best given by Lincoln. In the first debate with Stephen Douglas, in 1858, Lincoln said, “Let me say I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist amongst them, they would not introduce it. If it did now exist amongst us, we should not instantly give it up.”

By beginning his book with how he benefits from white privilege, he invites his white readers to join him in seeing our situation as similar in certain ways to that of the slave owners. This can be viewed as yet another consequence of applied empathy.

At a time when the left is calling for reparations for African Americans and for drastic steps to address the climate crisis, the right digs in with absolute rejection of any such measures. The racial component of that rejection is well known and implies that the right is not willing to give up perhaps the last remaining social pleasure of slavery: that they will always have Blacks beneath them. But Gay points to a very different component—the defense of pleasures. For example, there are individuals who say that whatever is happening to the climate, they don’t want to give up [fill in the blank], which is reminiscent of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, all of whom were uneasy about their owning of slaves, yet all of whom found it impossible to forgo the pleasures that slavery provided.

Gay implies a connection between pleasures and the willingness to go to war to defend them. He shows that a threat to the arrangements that provide basic pleasures can be met with a ferocity that can suggest the desperate rage of

a hungry infant. ■

-

Richard Grose, PhD, is an associate member at IPTAR and is secretary for the IPTAR Board of Directors. He is an associate editor for ROOM and is the moderator of the Room Roundtable. He is developing a psychoanalytic theory of culture, which would include an account of the way pleasure functions in American culture. He has a private practice in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis in Manhattan.

-

Email: groser@earthlink.net

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |