PSYCHIC SPACE

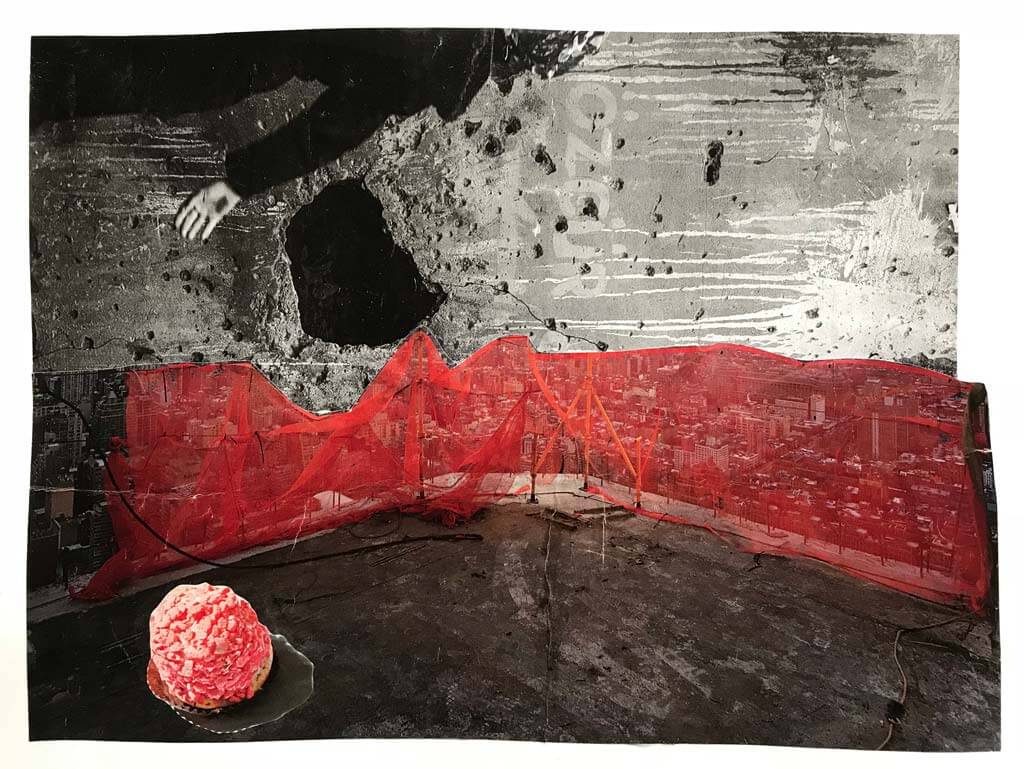

by Phyllis Beren and Sheldon Bach | Collage by Leah Lipton

When our yoga teacher first taught us to visualize the space between two joints in our body and then to breathe into that space to open it up, we followed her instructions avidly and were pleased with the results. It wasn’t until much later that we realized she was assuming that the mind could act on the body and that the body could act on the mind — that is, that the mind/body separation did not exist in Eastern practice in the same way that it does in Western medicine.

It was easy enough to imagine the mind affecting the body under certain circumstances: how our mouth waters when we are hungry and think of a great meal or how our body stiffens when we remember a traumatic situation. But how do we imagine a space between two joints and then fill it with air? Nobody had taught us how to do that, and yet, it seemed to work in a satisfactory way and to get better with practice when we tried it.

So it seemed as if the teacher’s external suggestions to focus could influence our experience of internal bodily space and when we learned how to meditate, it could also influence our experience of internal psychic space as well. But psychic space seemed to be more of a problem. Everybody knows it without being quite sure what it means.

None of the standard psychological reference works contain an entry for psychic space, and although PEP gives over two thousand references, a cursory glance shows little agreement. By “psychic space,” we mean simply the experience that people have of a space in their minds that usually includes their body, like the space of the room that they’re sitting in. This space can become infinitely large, like in an oceanic experience, or closing in to crush them, as in a claustrophobic experience. In both the oceanic experience of merging with a world of increasing infinite space and the claustrophobic experience of increasing loss of space, there is also an accompanying loss of the sense of agency. Indeed, the feeling of control or agency seems a most important factor in determining the meaning attributed to the experience of space and whether it is pleasurable or frightening.

Oceanic experiences, if self-induced or accepted, are often enjoyable or even ecstatic, and whether they are actively experienced as “I am taking over the world” or passively surrendered to as “the world is taking me over” or experienced symbiotically as “the world and I are merged,” they can have a pleasurable, spiritual, and sometimes religious connotation. If, on the other hand, the feeling of space expanding is neither wished for nor welcomed but experienced as a loss of control and traumatic impingement, it can become a terrifying harbinger of annihilation anxiety and loss of self.

Feeling that one’s psychic space is contracting can also be pleasurable or frightening, depending on the context and one’s sense of agency. If we are intensely concentrating on a task, physical or mental, we may experience a narrowed psychic space, or “tunnel vision,” that can be both isolating and yet also extremely gratifying. Many creative people prefer to work at night because external stimulation is minimized and other people are not around to distract them from this narrowed, concentrated vision. On the other hand, the closing in of physical and psychic space that is not under one’s control can lead to terrible fears of being crushed, of drowning, of being unable to breathe, and of being annihilated. We have only to remember the experience of a panic attack or think of Poe’s story “The Pit and the Pendulum.” In real life, there is considerable experimental evidence to show that animals become more disturbed, violent, and aggressive as their cages become more and more crowded and their personal space narrows. Anyone who has traveled in a terribly overcrowded subway train can attest to the narrowing of both physical and psychic space and its effects on one’s mood and sense of agency.

So presumably, for each person, there is also an ideal physical space and a psychic space in which they feel most comfortable and in which they also experience an optimal sense of agency and creativity, in which they feel most themselves. We each aspire to or may even be lucky enough to have found this ideal room of our own.

But we want to suggest that, in the world we live in today, both our physical and psychic space is being increasingly impinged upon, with dire results.

Of course, the people who are reading this belong, for the most part, to that small portion of the world’s population who have, in fact, homes of their own and perhaps a space of their own. But even we happy few are experiencing cities that are becoming overbuilt, subways and highways that have become dangerously overcrowded, schools and hospitals that cannot accommodate all who need help, a climate that leaves less and less room for adaptation; in short, our physical space is shrinking.

In a less noticed but more dangerous way, our psychic space also seems to be shrinking at an alarming rate. If we conceive of healthy psychic space as the space that promotes the greatest sense of agency and of individual creativity, then the incessant din from ringing cell phones, repetitive emails, loudmouthed newscasts and commercials, and a flood of information that substitutes quantity for quality impinges on us in a daily way that narrows our sense of psychic space. It was perhaps just as overexciting and probably less safe to walk down the streets in Elizabethan times, but it did not intrude into every private space in the way that our cell phones now follow us into the bathroom.

Along with the increasing spread of up-to-the-minute media that follows us everywhere we go, even more dangerous is the deliberate spread of misinformation or disinformation by parties who, consciously or unconsciously, are intent on producing chaos and destroying existing structures. Frightened as we are of terrorists with suicide vests that explode and spread shrapnel everywhere, this disinformation spreads fragments of lies and half-truths that fill our minds with lethal garbage and destroy our psychic space. We become swamped in toxic waste; we feel closed-in and our vision dims; we can think only in binary, either-or terms.

Being hammered by this barrage of half-truths, lies, and disinformation is like being interrogated twenty-four hours a day, under bright lights, by secret police; it induces a sleepy, drugged state of consciousness in which psychic space is dangerously narrowed and one’s only desire is to escape, to go to sleep, or to surrender and make it stop. All of this interferes with our ability to think and, above all, to think as creative agents. Is there any possible way of saving ourselves from having our psychic space foreclosed and our sense of agency exterminated?

We believe that the work we do in psychoanalysis directly affects this, for in our work, we are actually helping people to open their minds and raise their level of thought and consciousness. We help them to substitute secondary process thinking for primary process, to connect digital moments so they can achieve a continuity of being; hold the past, present, and future in perspective; and understand the influence of the present on the past and of the past on the present and the future. We help them to grow beyond binary thinking, to understand that the analytic process is itself the gradual process of life and to tolerate this slow process of authentic change that allows for more nuanced thinking.

We live through with them their anger and guilt, their feelings of parricide and matricide, and we help them reframe their lives so they may once again be able to love and to work and to be fully alive and creative. Helping with all this helps to expand their psychic space and makes them able to own their agency and their life once again — or perhaps even for the first time.

In this process of working with patients, we also help ourselves, for relating to another person in this constantly devoted way is a life-giving experience for both people that expands our own psychic space, refurbishes our own sense of process, and leaves us with humility at the miraculous, intimate encounter of one human being with another. In the burning heat of the clinical engagement, values, morality, empathy, and truth take on real and powerful meanings and are no longer just empty shibboleths. Filling psychic space with real emotional meaning replaces despair with hopefulness. All of this has been said before and said better, but we need to constantly repeat it in the face of the growing assaults on our space, our thinking, and our sanity.

We also go on marches together and speak out in the public space and urge others to speak out and to talk to one another. Each one uses his or her creative powers in whatever way she can. This is our way of fighting back against what, at times, can seem to be a volcanic eruption of crimes and lies that threaten to foreclose our space and cut us off from our very sense of aliveness and creation. This is one important way that psychoanalysts can fight back! —

Join our Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/analyticroom/

- Phyllis Beren, PhD, is a past president of IPTAR, a fellow and faculty member and director of the IPTAR Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training Program. She is editor of the book Narcissistic Disorders in Children and Adolescents and has written papers about child, adolescent, and adult treatment. She is currently writing a memoir. Email: pberen72@gmail.com

- Sheldon Bach, PhD, is an adjunct clinical professor of psychology at the NYU postdoctoral program for psychoanalysis, a training and supervising analyst at the Contemporary Freudian Society and the Institute for Psychoanalytic Training and Research, and a fellow of the International Psychoanalytical Association. He is the author of several books on psychoanalysis and of many papers, some of which have been collected in Chimeras and Other Writings: Selected Papers of Sheldon Bach. He is in private practice and teaches in New York City. Email: sheldonbach@gmail.com

- Leah Lipton, LCSW, is a psychoanalyst and collage artist in New York City. She is a supervisor at the Institute for Contemporary Psychotherapy (ICP) and a faculty member at ICP and the Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Study Center (PPSC).

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |