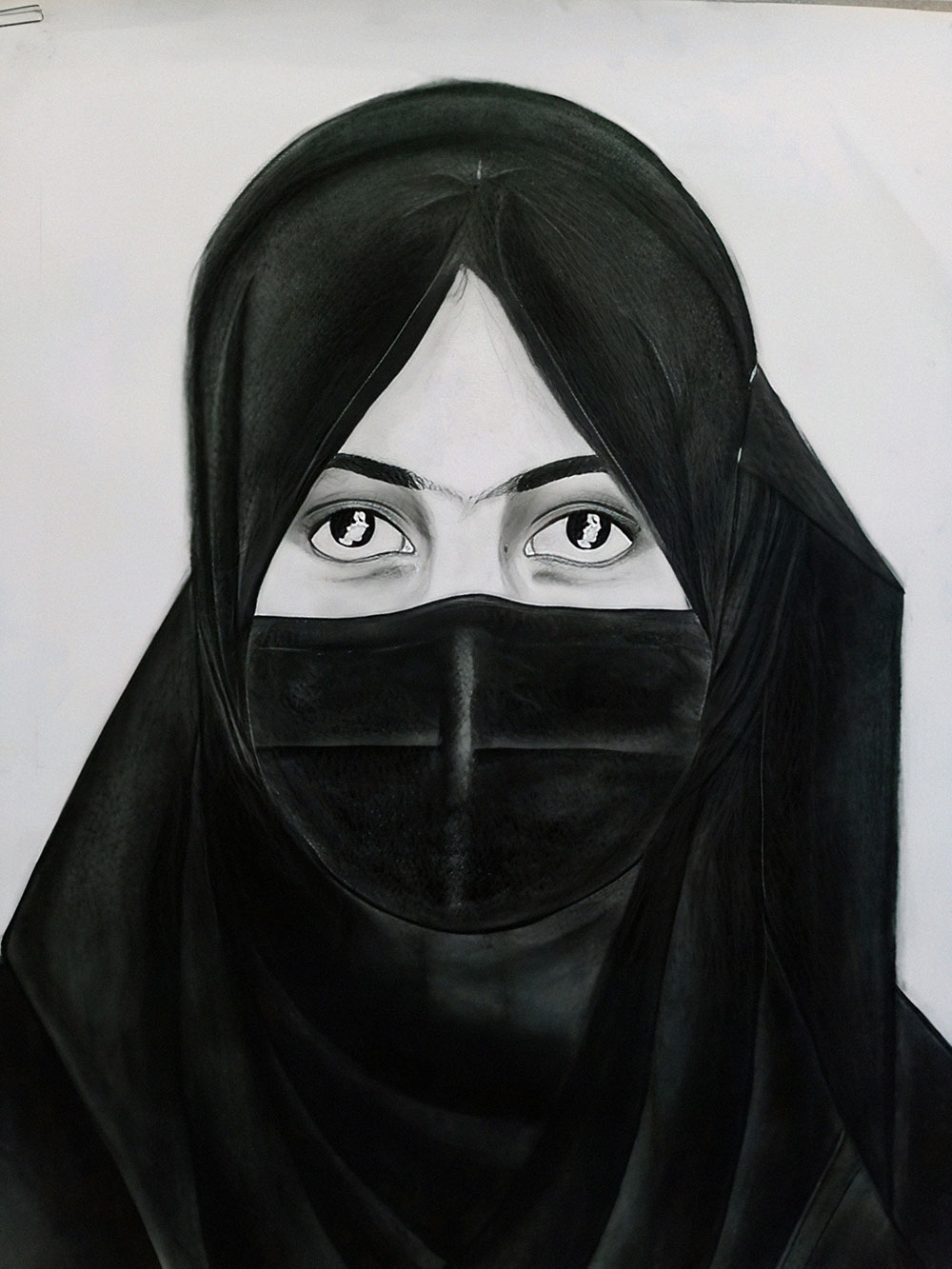

We Are the Light: No. 3

I created this piece inspired by the image of a girl who carries, in her eyes, the scene of a man shouting at a woman. Within this work lie thousands of hidden sorrows, the bitter moments that every Afghan girl and woman has witnessed: moments of humiliation, disrespect for her dignity, and the violence of being beaten. I created this artwork to raise awareness in the world about the harsh realities Afghan women and girls endure in their struggle to continue living. May this piece stand as a symbol to amplify the voices of Afghan women.

— Fearless

In the Shadow of Flight: The Story of an Afghan Family

A True Narrative in the Words of Beheshta Khan*

By Sadaf Asad

Rustum Khan and his wife Beheshta were a small, happy family in Bagram. Alongside their three children, two sons and a daughter, they led a peaceful life near Bagram Airfield. Rustum Khan worked proudly for years as a cook for the U.S. forces, earning a good living and providing his family with a measure of comfort.

But one day, Rustum Khan was kidnapped by unidentified armed men who intended to kill him. Miraculously, he managed to escape from the room where he was held captive. Recognizing one of his captors, he rallied the local community, forced that man to pledge he would be held responsible if any harm came to him.

From that day forward, however, Rustum Khan’s life was never the same. A constant fear of another attack settled deep within him. He decided to leave his job and flee with his family to Iran. Though they faced countless hardships along the way, they eventually reached Iranian soil.

A year later, after enduring mistreatment from some locals in Iran, Rustum Khan decided to move on to Turkey, but lacked the funds to secure passports and visas for everyone. Left with no legal option, they turned to smugglers. One night, while speaking by phone with Beheshta, I heard the exhaustion in her voice, but also a flicker of hope. As she began to recount their ordeal, I was no longer just a listener، I became a fellow sufferer.

Below is her own raw, sorrow-filled account, told with both grief and unwavering honesty:

Beheshta Khan

My dear sister, my heart is so heavy tonight… I need to tell you about one of the worst, most unforgettable nights of my life, a night etched in my mind like a dark painting. About two months ago, we set out for Turkey with a smuggler who promised it would be just an hour’s walk and that everything would be easy. But the reality was far different. Four times, under cover of darkness, we trekked from an Iranian village to the Turkish border, only to be sent back. With three little children, every attempt was agony. Finally, on the fifth try at four o’clock in the morning my husband decided to risk one more crossing. Our nine-year-old son urged him, ‘Father, we’ve suffered so much already, let’s try one more time.’ And so we moved forward. It was bitterly cold, and the guide told us to hide beneath a tree until sunrise. We were shivering. When the sun rose, we set out again. By six a.m. we struggled across the border. A patrol approached and everyone ran except me. I froze in fear. My husband took my hand and whispered, ‘Don’t be afraid; I’m with you.’ We walked for hours until we reached a Turkish village where people baked bread in clay ovens and lived simply. That night, mounted men arrived on horseback. Those who had money were carried off on the horses; the rest had to walk. From six in the evening until midnight, we ran through thorny, rocky mountains without stopping. Our knees were shredded by thorns; I could hardly breathe. The children cried and were exhausted. Around midnight, they crammed us into a Turkish cargo truck – eighty people inside! At 6am the next morning, we reached the city of Van. All the other families were freed; we remained behind. When we called the smuggler, he said, ‘Send the money and I’ll send the location.’ Once he received it, he switched off his phone. We spent two nights in a makeshift dormitory, living on stale bread and a single can of yogurt. The next day, two hundred more migrants arrived. Half of them left; we still waited. At 10 o’clock, the police came and arrested all of us. They took us to prison. We were in jail for a week. After that, the police said they would take us to a refugee camp. Using that excuse, they took our fingerprints on documents we couldn’t even read, and then they sent us away.

Around sunset, they dropped us off near some mountains with only a bit of food and water in our bags. There were about 90 of us. They abandoned us in a place with no signs of life or any village nearby. We all began walking toward Iran again, this time on foot. During the journey, in the dark of night, my husband broke his leg and couldn’t walk anymore. I was left behind with my husband, his 14-year-old nephew, and our three young children. No one from the group of 90 people helped me carry my husband to safety.

My husband insisted that I go on with the children and leave him behind to die, saying otherwise we would all die. But I told him, “If we are meant to die, we will all die together, and if we are to live, we will all survive together.” That night, I had no one but God to turn to. I cried out for help many times. The children were crying, and my husband’s condition was getting worse. I gathered my strength and told myself that if I didn’t act, we would all die. I sat the children down and began clearing a path with my hands for about 100 meters. I wrapped my scarf around my husband’s broken leg, and he crawled forward little by little. Sometimes I held one side of him, and my husband’s nephew held the other side. He moved a few meters at a time like that. We continued like this the whole night. With every passing moment, my hope for life faded more and more. I truly felt like we had reached the end of the road. But close to dawn, I saw smoke from a fire far away. It gave me a spark of hope.

I left my children and husband near a large rock and ran toward the smoke. As I got closer, I shouted, “Help! Help!” My eyes were full of tears. Suddenly, I saw people coming toward me with rifles. I was terrified. They asked what was wrong. I said, “Please help, my husband’s leg is broken.” They replied, “If this is a trap, you’ll regret it.” I was scared, but I told them, “No, it’s not a trap.” Eventually, about 20 people came. One of them picked up my daughter, another lifted my husband onto his shoulders. Then I noticed they were taking my husband in one direction and my children in another. I panicked. But the man carrying my husband pulled out his gun and told the others, “They’re a family no one is allowed to separate them.” Then they returned my children to me.

We were together again. We walked about two minutes. He took us to his home. But when we arrived, I saw something worse than before. Nearly 100 people were gathered, trying to buy us like we were slaves. I was just crying; I couldn’t say anything. The man who saved my husband turned to me and said, “Sister, don’t cry. I won’t let anyone harm even a strand of your hair.” People were shouting.One man said, “I’ll pay 20 million tomans for them.” Another said, “These are my travelers! You must hand them over to me!”

That same man who helped us snuck us out the back and put us in a car to take us somewhere else. On the way, the driver said, “Maybe you did a good deed in your life, because the village you were in is full of thieves and kidnappers. They kidnap people and demand one million dollars or more. If the ransom isn’t paid, they either kill the victims or sell them to human traffickers.” We were taken to a house in the mountains. The man who had first saved us was there. His mother was a bone setter. She came and treated my husband’s broken leg. They gave us food, and we stayed the night there.

The next day, their leader told my husband, “You came to us for refuge, so we protected you. We won’t extort you. But my men risked their lives to keep your family together and fought with other groups. For that, you need to pay 30 million tomans. At that time, 30 million tomans was a huge amount of money. My husband called his sister in Tehran, who had our money. She transferred the 30 million tomans to that man. After that, they took us safely to Tehran.

Now we are in Tehran, stateless, without identity, and carrying memories that have wounded our souls. Life is challenging in Iran, and Iran no longer offers us refuge: if we do not leave within one month, we will be deported. I do not know what fate awaits us if we return to Afghanistan, given my husband’s history working with U.S. forces.

* All names have been changed for their protection.

No woman should be a victim

By Baran Rasoul (September 2025)

If I could directly enact a national policy, I would focus on eradicating violence against women in my country. Violence against women not only inflicts personal harm on an individual, but also deeply wounds the soul of a society and the future of a nation. A woman is the founder of the family and the educator of the next generation. When she is oppressed, the impact spreads to the entire society.

Violence against women is not limited to beatings and insults, but also includes forced marriages, prohibitions from education, restrictions on work, and sexual harassment.

Unfortunately, in some societies, women do not have the right to make decisions, the right to education, and even the right to live freely. Violence can be physical, psychological, economic, and even cultural. Physical violence is beating, burning, or even killing women for various reasons. Psychological violence has deeper effects. Insults, humiliation, threats, and stress that impact the minds of women. Economic violence is not giving women the right to work and study, forcing women to be financially dependent,

Cultural violence is preventing girls from going to school or university on cultural pretexts, customs and traditions that limit the role of women in society, giving preference to boys over girls in the family. Violence is not limited to the woman as victim. The children of such women grow up in an atmosphere of fear and anger and may become victims of violence in the future. This vicious cycle can only be broken by raising awareness, educating, and reforming laws.

Building support centres for women victims should be a priority. Many women cannot report violence due to fear, shame, or lack of access to justice. They must have a safe, easy, and secure environment to file complaints. Shelters, free counseling, and access to legal services. If every family, school, and institution knows its responsibility, it can build a future in which girls grow up with self-confidence and women live with security and dignity and develop their talents. Fighting violence is not only the responsibility of the government, but the responsibility of all of us, from families to religious, cultural, and social leaders. We must stand up and take action until the day comes when no woman is oppressed for being a woman. Ending violence against women is a political, social, and human need.

A Light in the Darkness

I am an Afghan girl. From a land where being a woman sometimes feels like a constant struggle. I have walked the streets of this country with dreams in my heart and hopes in my eyes, dreams of studying, learning, and building a future where girls can grow freely. For years, I sat in university classrooms with dedication and passion. I was a third-year law and political science student, with only two semesters left to graduate. I believed that I would soon reach the moment where I could defend human rights, especially the rights of women to be a voice for the voiceless, a defender of justice.

But everything changed.

The doors of the universities were shut. Not because we failed or didn’t try hard enough, but because we were girls. Thousands of us were suddenly pushed out of the academic world, not due to our inability, but because of decisions made far from our will and far from justice. It wasn’t just the closure of a classroom, it was the collapse of a dream, the silencing of hope, the theft of our future.

Those days were heavy with sorrow and silence. I would stare out the window at the empty schools and ask myself, What can we do when even breathing feels risky?

But I did not remain silent. I, the girl who had been denied education, became an educator. My path changed, but my mission remained. Today, in a small house, in the most discreet and hidden way possible, I teach young girls. My students range from seventh to twelfth grade. I do not only teach them subjects like language, history, or mathematic I teach them hope. I keep alive the fire of learning and the courage to dream.

This is not just a job for me. Teaching is resistance. Every lesson, every notebook, every whisper of understanding is an act of defiance against darkness. When I look into the eyes of my students, eyes full of curiosity and silent dreams, I see my younger self, and I feel the responsibility to help them reach where I could not.

But this path is not safe. Every night, I fear being discovered. I fear that someone might find out about our secret classroom. That my students could be harmed. That my family might be punished. And yet, I continue. Because I know that behind these lessons lie futures being shaped.

Some nights, tears silently roll down my face. I wonder: if we no longer have a future, why do we keep fighting? But then, I remember a student who once said, Teacher, when I grow up, I want to be just like you. And that sentence alone is enough for me to carry on.

I teach not only to educate, I teach to keep alive what they tried to bury: the light of knowledge.

Being an Afghan woman is more than a gender identity; it is a responsibility, a daily battle. Throughout history, Afghan women have not only suffered they have resisted. From brave women of past decades to today’s girls who risk their safety just to learn, we are all writing a new chapter of courage.

We, Afghan girls, are not only fighting for ourselves. We fight for our sisters, for the daughters yet to come, for generations who deserve better. Even when books are taken from us, we write. When schools are shut down, we turn homes into classrooms. When our voices are silenced, we scream through our actions.

Education is not merely about reading and writing. It is about empowerment. An educated woman becomes a strong mother, a wise teacher, and a courageous leader. When you deprive a woman of education, you don’t just deny her rights, you halt the progress of an entire society.

I’ve seen this transformation up close. Even a basic education changes my students. They begin to ask questions, to make decisions, to dream with confidence. This is why I teach. Because I believe in change, even if it starts small.

And yes, sometimes I feel broken. Especially when I touch the textbooks I once studied, now gathering dust. When I open my old law books, tears flow freely. These books were once the tools I hoped to use in courtrooms to fight injustice. Now, they’re silent witnesses of a dream that was paused. But even now, I learn from them because I believe that a teacher must always be a student too.

Some days, I feel hopeless. I wonder if all this effort is for nothing. But then, a smile is enough. The smile of a student who finally understands a concept. Or a question like, Teacher, how do you stay hopeful with all this hardship? And I am reminded that to live, is to carry on. To build, even when the world is trying to break you.

Maybe I won’t return to university. Maybe I’ll never receive that degree I dreamed of. But I am building something else now, not for myself, but for a new generation. A generation born into the hardest of circumstances but destined to live in a freer world.

I dream of the day when no girl in my country is banned from going to school. A day when universities reopen and all of us return proudly to the places stolen from us. Until that day, I will keep my light burning. I will write, teach, and speak.

Because I am an Afghan girl. I am not broken. I am not defeated. I have been wounded, yes. I have cried many times. But I am standing.

With hope in my heart, a pen in my hand, and a vision in my soul, I walk forward. I believe: darkness is never forever. And we, the girls of Afghanistan, are small, bright lights. Lights that will guide the way, even in the blackest of nights.

— The Sun’s Daughter

The Truth Behind the Headlines: Differences in the Provision of Health Services for Afghan Pregnant Women Under Taliban Rule

By Ayat Sazkizada (September 2025)

Pregnancy is one of the most sensitive and important stages of a woman’s life, requiring proper medical care and access to quality services. The condition of pregnant women in Afghanistan has always been affected by social and cultural circumstances. The recent political changes and the return of the Taliban to power have created significant differences in the provision of health services and women’s access to medical facilities.

Before the Taliban, although Afghanistan’s health system faced many challenges and shortages, pregnant women had relatively better access to healthcare services, maternity hospitals, and professional doctors. National and international support programs also played a vital role in reducing maternal mortality. However, after the Taliban takeover, restrictions on women’s movement, the reduced presence of female doctors, and limitations on the training and activity of healthcare workers have caused serious obstacles in maternal care.

After the Taliban – Access to Health Services:

• Many international projects have been suspended or reduced.

• Some hospitals face problems due to budget shortages.

• The Taliban claims security has improved and health centres remain open, but their quality and resources are very poor.

• Girls’ education in medical institutes and universities has been stopped. • There is a severe and increasing shortage of female doctors and nurses.

• Many specialists have left the country due to economic difficulties and restrictions.

• Women are still allowed to work in the health sector (out of necessity), but under restrictions such as separation from male colleagues and limited mobility. • Many midwives and nurses have either resigned under pressure or migrated.

• Importing medicines and medical equipment has become difficult due to the economic crisis and lack of funds.

• Support from the World Health Organization (WHO) and a few other organizations continues, but it is not sufficient.

• In rural areas, the shortage of medicines, doctors, and facilities is extremely severe.

Before the Taliban’s Return – Access to Health Services:

1. Access to Maternity and Delivery Services:

• Provincial and maternity hospitals were active.

• Female doctors and midwives were present in most districts.

• International projects (such as USAID and UNICEF) strongly supported maternity services.

2. Training of Midwives and Nurses:

• Midwifery courses in health institutes were widely available to girls.

• A large number of midwives graduated and provided basic services in villages.

3. Maternal Mortality:

• Maternal mortality rates had decreased because women had access to midwives and doctors.

• Although still high, the rate was much better compared to before 2001.

4. Rights of Pregnant Women:

• Women could freely visit hospitals.

• There was a higher presence of female specialists in clinics and hospitals.

The comparison of maternal health services in Afghanistan before and after the Taliban highlights a profound shift in women’s access to essential care. While the pre-Taliban period was marked by gradual progress, international support, and relative availability of female health workers, the post-2021 reality is overshadowed by restrictions, shortages, and growing risks for mothers and newborns.

Pregnant women, who should be at the centre of health priorities, now face barriers not only in medical access but also in their basic rights to education, movement, and professional support. The suspension of midwifery and nursing programs has endangered the future of maternal healthcare, while the departure of specialists and the collapse of international aid projects have intensified the crisis.

Despite the Taliban’s claims of improved security and open facilities, the reality for many women—especially in rural areas—is one of uncertainty, lack of medicines, absence of trained staff, and preventable maternal deaths. The increasing dependence on unskilled birth attendants signals a reversal of two decades of progress.

Ensuring the health and dignity of Afghan women requires more than survival-level services. It demands recognition of their right to education, mobility, and professional healthcare. Without urgent national and international interventions, the future of maternal health in Afghanistan risks becoming one of silence, loss, and avoidable tragedy.

Justice For All or None at All

Don’t the fish in the aquarium ever miss the ocean?

Isn’t this limited space more depressing for them?

We, as humans,

in our pursuit of mixing life with happiness and freeing ourselves,

are willing to imprison any creature

and separate them from their world.

It’s true that we are considered the most honorable

of all creation;

but who gave us the right to lock birds in cages

just so they can sing

for our pleasure?

How is this any different from the system of slavery during the times of ignorance?

Freedom is the undeniable right of every living being—whether human or animal.

Those whose minds are narrower

and whose understanding is smaller,

they give less and value less.

In no religion is it acceptable to imprison or restrict

humans,

animals,

or even thoughts.

A person can limit someone’s sense of security through their actions;

Can restrict trust through betrayal;

Can limit another’s humanity through disrespect;

And finally, can confine someone’s kindness through ingratitude.

— Kemya (September 2025)

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |