Canvassing as Political Therapy

by Cathy Sunshine

Shortly before the 2016 election, I drove from my home in DC to Pennsylvania, ready to knock on doors to keep Trump out of the White House. I spent five days in York, talking to voters on front stoops in this aging postindustrial town. Home in time to watch the election-night returns, I settled in with beer and pizza to witness what every poll predicted would be a Clinton victory.

But the outcome was clear by midnight, and around 2:30 a.m. Clinton called Trump to concede. Awakening with a start at four in the morning, I felt like I couldn’t breathe. But I knew it was the beginning, not the end.

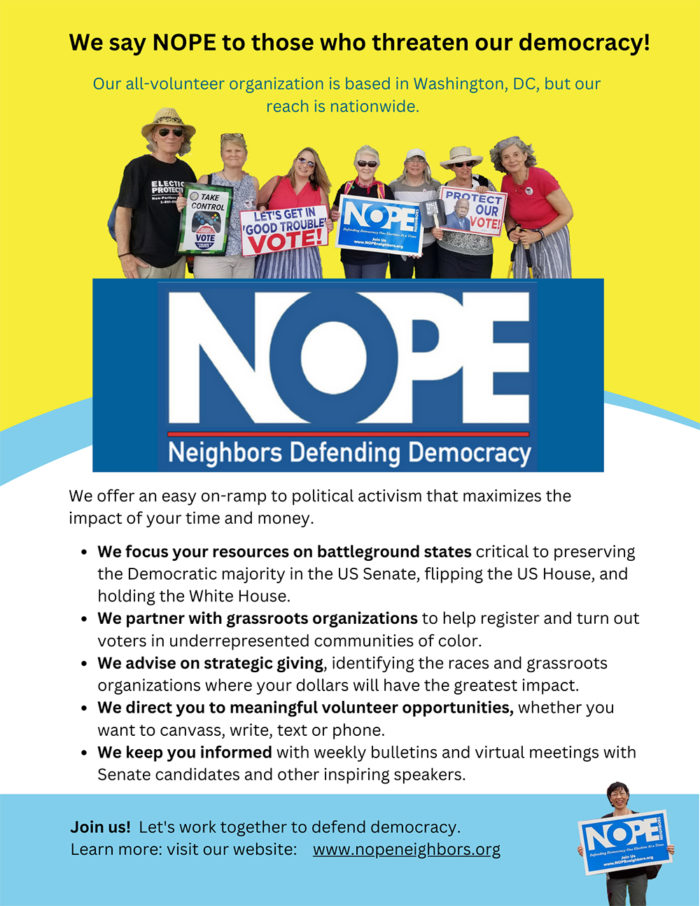

Over the past six years I’ve trudged through cities, suburbs, and rural swaths of Virginia, the nearest swing state to DC, canvassing for Democrats up and down the ballot. I often go with friends from NOPE: Neighbors Defending Democracy, an all-volunteer group that does canvassing, phone banking, fundraising, and voter protection for candidates and community groups in battleground states. Research shows that face-to-face contact is the most effective way to change minds and get hesitant voters to cast ballots. We canvass to swing tight elections; just as much, we canvass for ourselves.

Debra Fried Levin, leader of NOPE, calls door-to-door canvassing “political therapy.” After Trump was elected, she says, “People were distraught. There was a sense of helplessness. Yelling at the television did nothing; we needed to turn our fears and frustration into action. At NOPE, we’ve learned that directing our worries into knocking on doors and talking to real people—getting outside our blue bubble—is effective, both politically and personally. It offers a sense of community and hope.”

How hard is it to chat up strangers about politics in this polarized age? Not as hard as you might think, according to three NOPE volunteers I asked. Talking with voters from across the political spectrum, even those who disagree with you, turns out to be surprisingly constructive. I spoke with Debbie, Liz, and Renee on October 11, 2022.

Cathy: How did you all come to be knocking on strangers’ doors?

Debbie: I’ve been politically active my whole life. I started canvassing with my father, who was a precinct chair in the Chicago suburbs. Later I worked for the Communications Workers of America, and about twenty years ago, labor started having its members knock on doors of fellow union members. So I canvassed through the union political program.

Liz: I, too, am a longtime canvasser. The first person I canvassed for was McGovern, when I was in college.

Renee: I was never involved until the Hillary campaign in 2016. A friend asked me to go to North Carolina with her and get out the vote the weekend before the election. And obviously the election didn’t go well, but the canvassing was so much more fun than I had realized it could be. My first thought afterward was why didn’t I do more? I don’t have a right to complain if I’m not willing to do anything.

Cathy: Renee, is knocking on doors different than you expected?

Renee: It is. I was intimidated the first time. But I was surprised at how willing people are to talk, even just to say “I don’t really follow politics.” We ask, “What’s on your mind?” You can start all kinds of conversations. People have said repeatedly, “I’m so tired of the ugliness. I’m so tired of the polarization.” And we’ve encouraged people to vote, even when we found out they weren’t voting our way. We’re not angrily stomping off. Right now, when people explicitly say “I’m so tired of the fighting,” to have someone be polite to you who doesn’t agree with you is really nice. So I find it easier than I ever thought it could be, and more uplifting and encouraging and interesting. It’s just not as scary as it seems.

Debbie: I remember knocking on the door of an African American family right before the 2008 election that Obama won. The entire extended family had come to that home to have a pre-election dinner to prepare for what was, for them, the most exciting day—voting for an African American for president.

Cathy: I was canvassing in York, Pennsylvania, before the 2016 election. A man came to the door who didn’t speak much English, but when I switched to Spanish he was happy to chat. The whole family is voting, he told me. Yes, voting for Clinton. But his wife, from another room, called out, “No, no, la mujer!” The woman! And the man and I reassured her together: “Clinton es la mujer!” Clinton is the woman.

Debbie: Last weekend I rang a doorbell—it was a Ring video doorbell—and somebody came on and said, “Hello, who are you?” Ring doorbells, you can answer them on your phone. I explained that I was canvassing. She said, “Wait a minute, I’ll be there,” and she drove from around the corner. We had a lovely conversation. She was a very strong supporter, and she gave me a big hug.

Cathy: How do you deal with rude or unfriendly people?

Debbie: There aren’t that many. You say “thank you very much,” and walk away.

Liz: I had someone—he wasn’t rude or unfriendly, but he was totally conservative and started out a little antagonistic. We ended up talking, and he said, “Thank you for doing this. This is what democracy ought to be about. And I’m never going to agree with anything you say, but I’m glad you’re here.”

Cathy: In 2018 I was canvassing in an affluent suburb in Virginia. I rang the doorbell of a big house, and a harried-looking woman came to the door. She asked what my candidate, then running for Congress, had accomplished during her time in the Virginia legislature. “Well,” I said, “she helped expand Medicaid in Virginia.” And immediately I thought, what a dumb thing to say. This woman is very well off, and she’s not going to care about that. But her face changed, and she said, “You know, when I divorced, I lost my husband’s health insurance, and the children and I are on Medicaid.” And I thought, wow, don’t make assumptions about people. You never know what their circumstances are. One reason I like canvassing is that you get a glimpse of lives that are unlike your own. It takes you out of your own reality and into other people’s, seeing their neighborhoods, their houses, how they live.

Liz: In 2016 I knocked on a door in a working-class neighborhood, and a man came out with his young daughter. I made my pitch for Clinton. And he said to his daughter, “Can you go back in the house.” Then he said to me, “We’re really struggling to get by. I’m in construction. I can barely make the house payments. And there’s so many immigrants coming in, taking the jobs that I would like to get.” How do you respond? You can make the academic argument that immigration isn’t what’s driving unemployment. But it’s also a moment for empathy. He wasn’t just being ideologically Republican. He was deeply worried about his family and didn’t want to say it in front of his daughter. So it was a moment for me to learn.

Renee: People want to tell their stories. When someone says something inflammatory, if we just nod and say, “I hear what you’re saying,” they come down a notch.

Liz: I’ve only once had somebody be rude. I knocked and they didn’t answer. They had a “no soliciting” sign. I left a flyer and got back in my car, and he came out the door and said, “Did you see my sign? You’re trespassing! You can’t be here! I’m gonna call the police!” And I’m like, “Yeah, great, fine. We’re leaving now.”

Cathy: Do you think canvassing works?

Liz: There’s research that says that canvassing, of all the different methods of voter contact, is most likely to increase the odds that someone will vote or persuade them to vote for a certain candidate. I believe that someone is more likely to vote if you were friendly and they made a sort of commitment to you to go out and vote.

Renee: It takes me a couple of knocks to figure out how not to sound like I’m reading a script, how to be folksy and friendly but not like I’m acting. It starts off awkward, but then it becomes natural, and you end up having a good time.

Debbie: Friends who say, “Oh, I’m so hopeless”—I just feel like there’s many things you could do. Canvassing is one of them, if it works for you. But do something. It helps you find people who are like you and overcome that sense of hopelessness.

-

Debra Fried Levin leads NOPE: Neighbors Defending Democracy. For most of her career, she has raised money for political candidates and nonprofit groups, including US House, Senate, and vice-presidential candidates, as well as Florida State University, the Democratic Leadership Council, and NARAL, among others. She founded and leads a fundraising coaching nonprofit, MatchDotDollars (MatchDotDollars.org). Since 2017, working as a volunteer, she has spent most of her time leading NOPE.

-

Cathy Sunshine is a freelance writer and editor in Washington, DC. She volunteers with NOPE: Neighbors Defending Democracy and edits their weekly newsletter, which goes out to activists across the country. She is the author of the blog Third Age, which considers the political and personal experiences of women in midlife and beyond.

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |