From Hand to Hand

by Hattie Myers

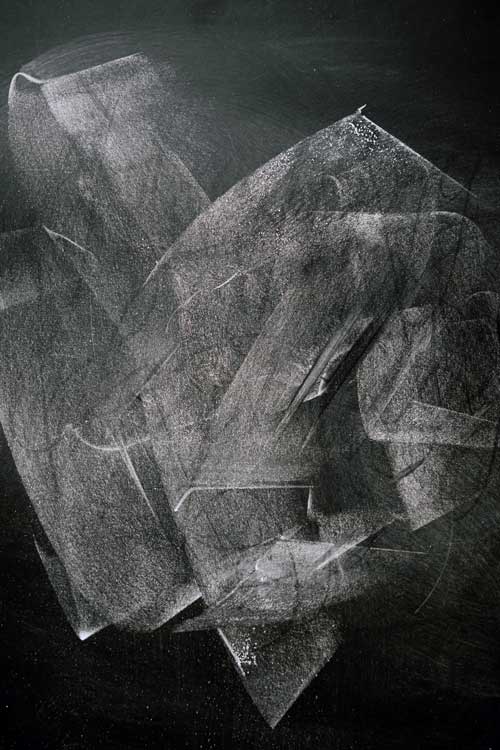

I have a fading flower in my hand

Don’t know to whom I’ll give it on this foreign soil.

—Landay poem by an anonymous Afghan woman1

“It turns out that when you meet the president of the United States, you are not allowed to have anything in your hands or your pockets, so the fact is I couldn’t show President Biden Shegofa Shabazz’s ‘Letter to the UN’ published in ROOM 6.23. I could only tell him about it,” Layne Gregory wrote to me, correcting a rumor that had been buzzing about. Layne Gregory is one of the founders of the Asian University for Women’s program Writing for Friendship.

None of us, and perhaps least of all Shegofa, ever imagined that her “Letter to the UN” (which had been rejected by at least four different magazines and newspapers before we published it) could have had such reach. Nor could we have imagined that within weeks the IPA UN subcommittee would invite Shegofa to speak to them, register a formal human rights complaint on her behalf, and work actively to find other platforms to amplify her voice.

ROOM is more than a magazine. It was conceived as a psychoanalytically informed community platform following the 2016 US election. Our editorial process is unique. In keeping with our belief that lasting change can only happen from the ground up, we open our doors and wait for readers to write. We never know, from issue to issue, what will rise to the surface of our collective consciousness. Like Shegofa, the authors of ROOM 10.23 are hoping against hope that their words, which are so particular to their separate histories and psychologies, might be heard, might have an impact.

But hearing them may have just gotten harder. The essays in this issue were written months before the horrors which are now unfolding in the Middle East. As I write this editorial, I am aware that it may now be more difficult for some of ROOM’s readers to read Diana Moga, a Jew, and Abdel Azziz Al Bawab, a Palestinian, describing their experiences. “Dispossession is simply an ingredient of my identity,” writes Bawab in “A World Not Good Enough.” “And yet this identity, so saturated with pain, I came to realize is a nuisance to others.” For Diana Moga, “Psychoanalysis has been a way to hold on to conflicting world views, a way to make sense of (her) fragmented past and the pluralities of (her) identity.”

But is it still?

In her essay “Breaking Narratives,” Moga tells us she was “disappointed and heartbroken when (she) heard that Dr. Sheehi could not present her analytic work with Palestinian patients at ApsaA’s June conference.” Eric Shorey is cautiously more optimistic. In “Dragging Psychoanalysis,” he implores our field to not just make room for the queer community but to go further and risk being transformed through the connection. “If psychoanalysis wants to make amends with the queer community, it will have to confront certain assimilationist assumptions inherent in its thinking.”

ROOM 10.23 is all about taking risks. Some authors, like Dean Hammer and Robert Frey, recount risks that landed them in jail or simply came to naught. “The sound of hammers disarming mass-killing weapons [still] echoes in my mind, heart, and soul…” writes Dean Hammer in his “Reflections on Plowshares Eight.” “Our midnight mission may not have had the dramatic effect we’d hoped, but at least we turned our conviction into action,” recounts Robert Frey in “Midnight Mission.”

Others, like William Cornell and Elle Wynn, describe the life-ending risks involved when impenetrable walls are constructed socially or psychically to ward off, in Cornell’s words, a “complex web of profound loss, abandonment, and shame.” “When I heard he was Black, my immediate thought was that he was truly fucked, that he’d be dead in an hour,” writes William Cornell in “A Sovereign Nation.” “The sense of security [in the senior housing project] was false: there was nothing to keep these vulnerable individuals safe,” Elle Wynn recalls in her essay “A Lack of Interest.” Both of these authors experienced firsthand reality blasting through illusions of safety. They are not speaking metaphorically.

In “Beyond Reason,” John Alderdice also makes it deadly clear that nothing we are experiencing today is metaphoric or illusory. “At this inflection point in human history,” he writes, “it remains an open question whether global leaders and their followers can put shallow, selfish, short-term political and economic interests aside in favor of global peace, stability, and reconciliation or even the survival of our own species, but the alternative is too terrible to contemplate.”

Alderdice recalls the work he did with “three interlocking sets of disturbed historic relationships” in Northern Ireland and how essential it was, when facing existential threats, to develop new ways of thinking and working based on “complexity theories and the full breadth of human knowledge and science.” His recognition that “old forms of understanding and ordering society are dissolving for reasons that are not so different from those faced by our predecessors half a millennium ago” leads him to hope against hope that if dramatic paradigm shifts had been possible once, surely they must be possible again.

Josephine Wright’s “Pages in the Park” entreats us to look even further back when she finds a copy of Antigone that a stranger left on a park bench with the day’s date penned above Sophocles’ words “I have seen this gathering sorrow.” Wright can only wonder whether “the dismembered book (was left) on this bench for others to be stirred and provoked by the discourse on responsibility, moral choice, self-examination, and action inherent in Sophocles’s remarkable words.” Whatever the stranger’s intention, Wright’s reflections pass their gift on to us.

Writing is risky, and at this pivotal moment in our history it can be an act of moral defiance as it was for Sophocles. In “Building Connection and Resilience,” Carol Geithner shows us how it can also be an act of love. As one of the young women in her group wrote, “I cry for my entire country as the sky does for the whole planet.” And in reading her words, we can cry with her, she is just a little less alone.

For over a thousand years, Afghan women have sung twenty-two-syllable poems called Landays, a name derived from the Pashto word for a sharp, poisonous snake. Landays are improvised as women get water from springs, cook together in kitchens, work in the fields, and dance at celebrations, and the most powerful ones, like the one in the epigraph above, become anchored in collective memory. The poems of Afghan women, like many of the poems, essays, and memoirs of our ROOM authors, are speech acts containing generations of grief, war, love, home, and hope. Some of the offerings in this issue of ROOM 10.23 are already anchored in collective memory, some will never be seen, and others are just now coming into being.

ROOM 2.24 is accepting submissions through January 5. Our hands are open. Our hearts are grieving. We are holding space.

1 Sayd Bahodine Majrouh, Songs of Love and War: Afghan Women’s Poetry (New York: Other Press, 1988). Majrouh was a writer, politician, and dean of the Department of Literature in Kabul. While in exile after the Russian invasion, he founded the Afghan Information Center, which broadcast reports and analyses of resistance across the world. Songs of Love and War brings together all the Landays that Majrouh collected in the valleys of Afghanistan and the refugee camps in Pakistan. Majrouh was assassinated in Peshawar one month before its publication.

-

Hattie Myers PhD, Editor in Chief: is a member of IPA, ApsA, and a Training and Supervising Analyst at IPTAR.

-

Email: hattie@analytic-room.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |