RE-VISION

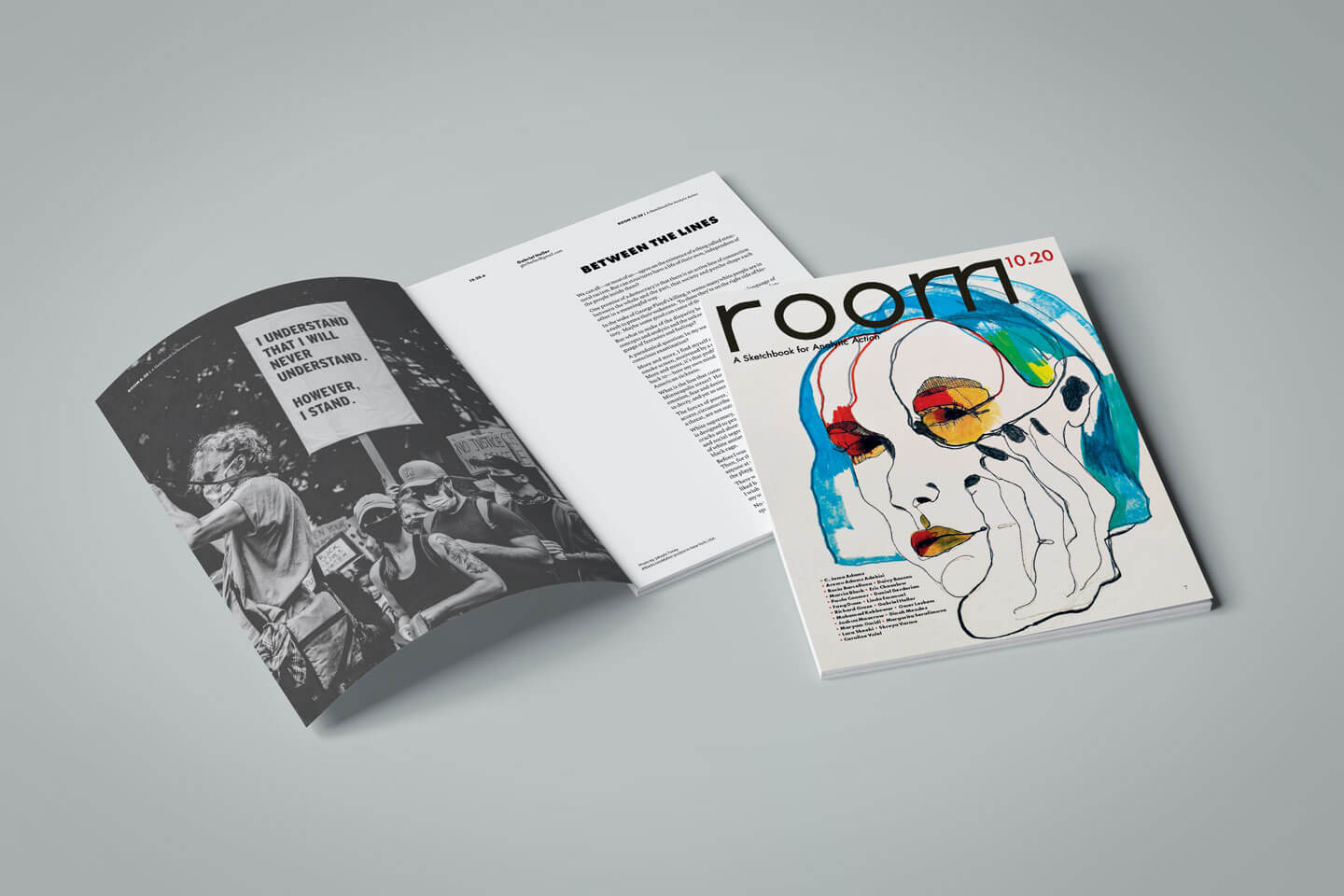

by Hattie Myers | Cover by Daniel Derderian, Grey Varnish (2020)

The day was departing, the darkened air was releasing all living creatures on the earth from their toils; and I alone prepared myself to undergo the war both the journey and the pity, which memory, unerring, will depict.

—Dante, Inferno, Canto 11 (1-6)

For Freud, nearing the end of his life, the fateful question for the human species came down to whether and to what extent our cultural development would succeed in mastering the disturbance our aggressive and self-destructive instincts inflict upon our communal life.

“Men,” he wrote in the last sentences of Civilization and its Discontents, “have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty exterminating one another to the last man. They know this and hence comes a large part of their current unrest, their unhappiness, and their mood of anxiety. And now it is to be expected that the other of the two ‘heavenly powers,’ eternal Eros, will make an effort to assert himself in the struggle with his equally immortal adversary.” Eros’s immortal adversary, Thanatos, was life’s somber and inexorable drive toward death. Two years later, in 1931 as Hitler ascended to power, Freud went back to this paragraph and added one last line, “But who can foresee with what success and with what result?”

Now as then, no one can foresee what will happen next.

With over a million souls dead from COVID, with droughts, fires, and floods rendering the earth uninhabitable; with the hatred and fear we train toward each other engendering new ruthless alliances; and with the US presidential election in just few days determining the fate of its democracy, if our “cultural development” is to succeed in assuring our survival, it must step in quickly. The analysts, poets, and artists featured in ROOM 10.20 are seizing this darkness as an occasion to illuminate a new beginning.

From the heart of a maximum security prison Rocío Barcellona bears witness to the depths our society has sunk to. In “Collective Disappearance,” she finds no hope. “I became aware,” she writes in the midst of the COVID epidemic, “of the spaces we inhabit between person and disappearance, marching toward and against erasure with our inmates. At times our presence is the only witness to their presence… Who will hold on to us as we fight to hold on to them, as we fight to convince them to hold on to themselves in a world that does not care if they let go?” Barcellona poses a question that is a touchstone in ROOM 10.20. “How do we treat ourselves and others like human beings…? How do we remain human?

“The image of human life so violently, and yet lightly, canceled in the name of law and order, state and authority, was deeply imbedded in the innermost recess of my psyche,” writes Fang Duan in her heart-stopping essay, “From an Other Perspective.” In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter movement, Fang Duan reveals a radical understanding she has come to about “otherness” in light of her own family’s blood-chilling history. In “Ancestral Spaces,” Marcia Black looks beyond and beneath what she calls “trauma’s rubble.” “As we find ways out of the imprisoned minds and disconnected/devitalized bodies created through colonization,” Black imagines that “…we might discover the guidance of ancestors who exist within us and whose ways of knowing carry wisdom waiting to be unlocked and opened.”

Would that we could find the key to unlock that ancient wisdom. In the meantime, Gabriel Heller in his essay “Between the Lines,” and Maserow, Leshem, and Omidi in their essay “Fire and Ice in Portland” get in closer to try to see better. Struck by “white people (who are) in a rush to prove their wokeness,” Heller wonders, “what to make of the disparity between our knowing language of concepts and analysis and the unknowing, ceaseless, subterranean language of fantasies and feelings?” “Fire and Ice in Portland” parses the deadly linguistic conflation of viral racism. “Doubling down on nationalistic and nativist values becomes a way of creating order out of and finding personal meaning in existential chaos. Dividing the world into all good and all bad provides people with a chimeric sense of mastery which dilutes death anxiety.”

As a former geriatrician and palliative care physician, Linda Emmanuel comes to psychoanalysis knowing full well how facing death and digesting loss must come to be “bounded by reality” rather than this kind of chimeric sense of mastery. She has named this developmental achievement “existential maturity.” And in “Learning from Chickens,” she illustrates that what is required to face the stark reality of our finitude comes not with age but through care—it comes with an internal sense of being held.

So what happens when what once held gives way: to a sudden catastrophe; to creeping pollution and political collapse; to war and pandemic? What morning can melt the darkness of this night?

In “Grief Suspended in Explosion,” following 190 deaths, 6,500 injuries, and over 300,000 people left homeless in Beirut, Lara Sheehi writes, “I can’t hold on to the space… The Romanticism of my soul, my longing, my desires are quelled, suspended alongside my grief.”

In “Pollution: The Case of India,” Varma writes to us from New Delhi, “My panic-stricken and recurring thoughts about the state of my country, my home, (are) haunting me like a waking nightmare.”

In “War and Pandemic in Aleppo,” Kebbewar writes, “During the epidemic, a simple handshake is more disturbing than a missile launcher near our home. The invisible danger is what makes the virus lethal… In war, even artillery needs to take a break…”

But amidst the grief, and terror, and horror for these authors, something is illuminated. For Varma it comes in the knowledge that she is not alone. “The feeling of terror that haunts me pervasively haunts every home in India today… Scared that I (was) alone, I stayed shut. Maybe we are engaged in a joint pathology as we rummage through and piece together our lives around these many horrific events.” Lara Sheehi understands that a new inner stability can come to be found in movement. “I am in a holding pattern — working to find a place for my Lebanese siblings… alongside a global solidarity struggle that feels more aligned …with every other liberation struggle to which my heart, body, and soul belong.” And from Syria, Mohamad Kebbewar finds unexpected possibility. “We no longer hear the sound of bombs… the sky is cleaner, and our minds are calmer. The virus made us aware of nature, climate, and the world around us. We don’t know how the world will resume its wars and lives. I hope it will be different…”

And what in our “cultural development” might support us as we totter on the edge of this cliff? In her essay “Psychoanalysis in the Community,” Caroline Volel, offers just this: “psychoanalytic compassion.” She writes, “It transcends race. It transcends class. It transcends disposition as long as one is willing to accept the mind-blowing concept that we are all, on some level, the same. The adopted lens of psychoanalytic compassion changes my outlook from ‘this is not’ me to ‘this is also me,’ in order to contextualize whatever is happening with whatever piece of myself that can understand it.”

But that is by no means all Volel has to say. As a pediatrician who has worked for decades as a civil servant for underserved and marginalized populations, she has been forced, she says, to think both largely and collectively. She argues that “psychoanalysis is a powerful tool that has been kept within exclusive circles. We have a responsibility to learn how to bring it to a larger community that has not had ready access to deep psychodynamic work.” She is not wrong, nor is she done. “We can examine collectively who we have othered if we ask our questions with both a critical eye and deep analytic honesty.”

C. Jama Adams and Dinah Mendes could not agree more. For both of them, change begins at home. In “Times of Rage and Opportunity: Thirteen Tasks for Analytic Institutes,” Adams moves between registers—challenging the trifecta of culture, organization, and self, while simultaneously offering a recipe to operationalize transformation in the psychoanalytic mothership of analytic training—the institute. Dinah Mendes takes psychoanalysis itself to task in “Fault Lines, Blind Spots, & Otherness.” Parsing two hushed-up problems brought to the surface by COVID and by the Black Lives Matter movement, Mendes talks about the financial access to psychoanalytic treatment, and the long-overdue need to identify racial otherness and othering within psychoanalytic theory and practice. She notes that “Pressures from within and without threaten the future of psychoanalysis, and it seems more important than ever to resist fracture and splitting and to seek common ground, and unifying belief, and commitment.”

James Baldwin wrote that “the loss of an empire implies a radical revision of individual identity.” Siding with Eros, the authors in ROOM 10.20 are saying radical revision is possible. It’s down to us. ▪

-

Hattie Myers PhD, Editor in Chief: is a member of IPA, ApsA, and a Training and Supervising Analyst at IPTAR.

-

Email: hatbmyers@gmail.com

ROOM is entirely dependent upon reader support. Please consider helping ROOM today with a tax-deductible donation. Any amount is deeply appreciated. |