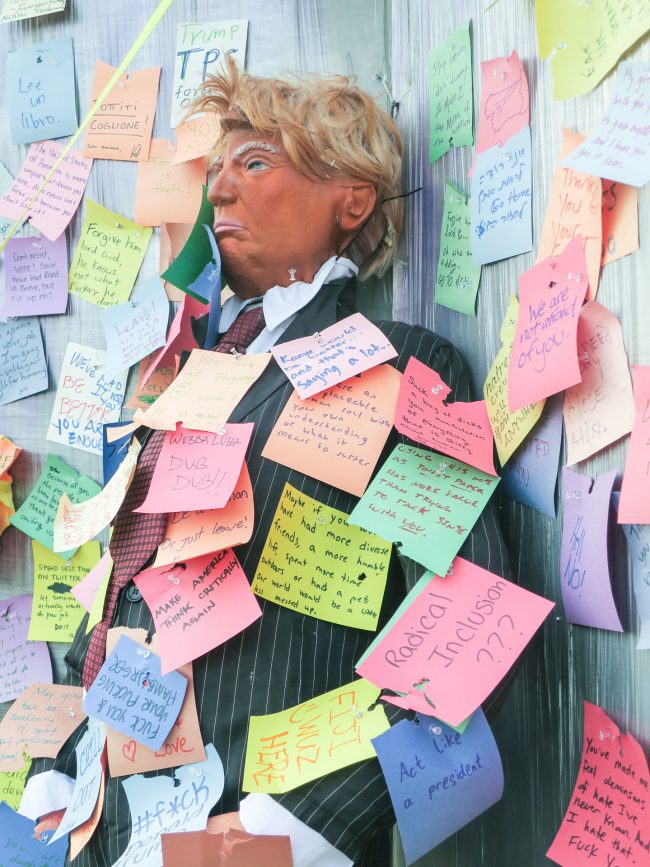

AN EVANGELICAL’S PERSPECTIVE by Jacob Andrew Smith

As we approach another long election cycle in the United States, news outlets will be reporting on the political trends of evangelicals. It is often reported that 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and they continue to remain faithful to him almost three years into the completion of his first term in office.