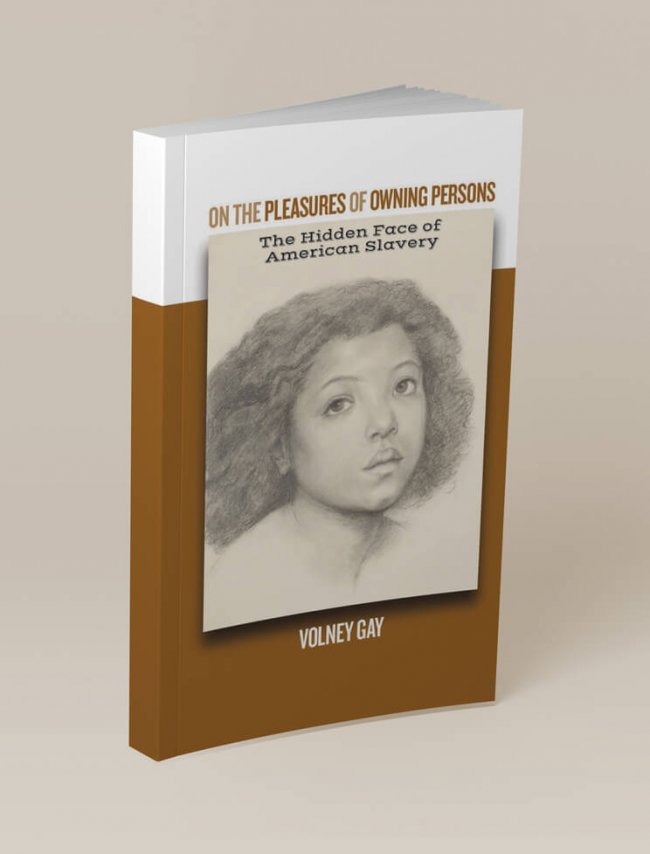

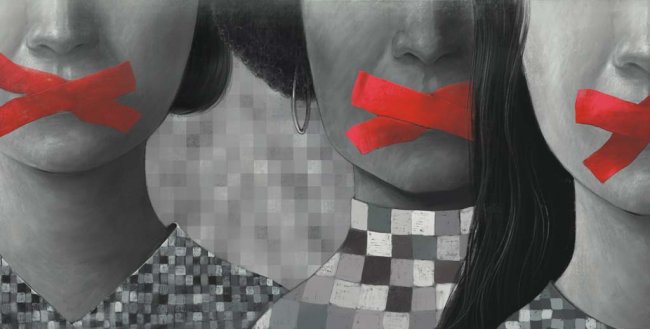

Another fixation of mine has been the impossibility of my ancestors, particularly the abducted and the enslaved. Through the wound which would be called the Atlantic Slave Trade, Black persons were simultaneously the subject, the object, and the labor. Put another way, Black persons were the commodity—something akin to a gold piece, the means of production—which we would now call human capital, though such a qualifier is missing in enslavement and, ironically, in the subject. In the case of Black persons, the traits of subjectivity—communication, relationship, organization, aspiration, ad infinitum—were forcibly recognized either in their negative (as in the forbiddance of some otherwise common human practice) or in their grotesque affirmation (such as with the concession of small pleasures or the mechanic exploitation of human impulses). In this way, the Black person is canceled out in a triple negative, an impossibly impossible subject, further complicated by their intercession with other unreal things.